The process of delegation involves the following steps: 1. Determination of Expected Results 2. Assignment of Duties 3. Authorization for Action 4. Creation of Obligations.

Process of Delegation (with Steps)

Process of Delegation – Top 4 Steps: Determination of Expected Results, Assignment of Duties, Authorization for Action and Creation of Obligations

The complete process of delegation of authority involves the following four steps:

1. Determination of Expected Results:

Since, authority is intended to provide managers, with a tool for managing as to gain contributions to the organisation al objectives, so it is essential that authority delegated to a manager is adequate to ensure the ability to accomplish results expected. Authority should be delegated to a position according to the results expected from that position. It implies that results expected from each position have been identified properly. Therefore, the first requirement is the determination of contributions of each position, which is largely a step undertaken at the stage of creating various positions.

2. Assignment of Duties:

The assignment of duties to the subordinates is the second step in this process. Duties can be described in two ways; first, these can be described in terms of an activity or set of activities e.g. selling activity to salesman. According to this view, delegation involves assignment of these activities by a manager to subordinate. Second, duties can be described in terms of results that are expected from the performance of activities, e.g. how much sale is to be achieved by salesmen.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Assignment of duties in terms of results expected works better because a subordinate is likely to get psychological satisfaction from his/her work and he/she will have advance notice of the criteria on which his/her performance is to be judged. A man’s duties will be clear to him only when he knows what activities he must undertake and what goals he must fulfill.

3. Authorization for Action:

This aspect involves granting of permission to take actions like making commitments, use of resources and other actions, necessary to get the assigned work done. In the delegation process, the manager confers upon a subordinate the right to act in a specified way or to decide within limited boundaries. The subordinate exercises the authority in conformity with his/her understanding of the intentions of the superior, who delegates it to him/her and within the framework of such controls as the superior deems it wise to establish.

4. Creation of Obligations:

This is essential aspect of delegation to create obligation on the part of subordinate for the satisfactory performance of his/her assignments. A subordinate is responsible for the total activities assigned to him and not only for the activities actually being performed by him. The sense of obligation required arises from the maintenance of responsibility by the superior and an accompanying insistence that the work performed must meet his expectations.

Process of Delegation – Top 5 Ways

Since, delegation results in several organisational advantages, it becomes necessary for the management to remove any barriers to effective delegation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Some of the ways are discussed below:

1. Delegation must be Complete and Clearly Understood:

The subordinate must know precisely what he/she has to know and perform. It should be preferably in writing with specific instructions, so that the subordinate does not repeatedly refer problems to the manager for opinion or decision.

2. Proper Selection and Training:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Before delegating authority, the manager/superior must properly assess the subordinate on the basis of his ability and limitations. There should be constant communication between them in order to build up superior’s confidence on the subordinate. At the same time, the managers must work closely with the subordinates in order to improve their job performance.

3. Motivating Subordinates:

Management must remain sensitive to the needs and goals of subordinates. The challenge of added responsibility itself may not be a sufficient motivator. Accordingly, adequate incentives in the form of promotions, status, better working conditions or additional bonuses must be provided for additional responsibilities well performed.

4. Tolerance with Subordinate’s Mistakes:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The subordinates are inexperienced in making judgments as the managers are, so they are bound to make errors in the process. Unless these errors are serious in nature or occur repeatedly, the management should not severely penalize subordinates but encourage them to learn from their mistakes. They should be allowed to develop their own solutions and be given sufficient freedom in accomplishing delegated tasks.

5. Establishing Adequate Controls:

If there are adequate checkpoints and controls set-up in the system, like weekly reports etc., then managers will not be continuously spending time in checking the performance and progress of subordinates and their concerns about subordinates performing inadequately will be reduced.

Process of Delegation – Steps Involved

1. Assignment of Responsibilities:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The manger has to decide the tasks to be delegated to the subordinates. For this, he must distinguish between the routine and non-routine tasks. Routine tasks can be performed by the subordinates, while the non-routine and important tasks must be performed by him.

2. Granting of Authority:

When the subordinates are assigned certain tasks, they need authority also to perform the same. Authority is required to use of the resources of the organization. The superior, therefore, transfers his authority to enable the subordinate to perform. Responsibility and authority both go together. Parity of authority and responsibility emphasizes the need for a proper balance between the two.

3. Creation of Accountability:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Delegation does not end with just entrusting of duties and the granting of authority. An obligation on the part of the subordinate to perform is to be created. In other words, the subordinate is accountable for the tasks delegated. Normally, accountability is created by asking the subordinate to submit performance reports/status reports from time to time.

Process of Delegation – Steps (With Examples)

The following steps are essential and they must be kept in mind while delegating:

1. The delegation should define the result expected from his subordinates.

2. Duties should be assigned according to the qualifications, experience and aptitude of the subordinates. They may be described either in terms of activity or set of activities to be performed by a subordinate or in terms of results that are expected from the performance of activities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For Example – How much sale is to be achieved by salesman? It is better to assign duties in terms of results expected, because the subordinate knows in advance the terms in which his performance will be judged, while assessing duties and responsibilities.

The delegator must ensure that subordinates understand and accept the assignment, otherwise delegation would be meaningless or ineffective.

3. Adequate authority must be given to subordinates – The authority to be delegated to each particular subordinate is determined in advance. The delegator confers upon the subordinate the right to act in a specified way within limited boundaries. It decides what actions we may take and what action we cannot take. Proper authority to any subordinate not given in time, will not give or produce expected results.

For Example – A sales manager, charged with the responsibility of increasing sales of company’s product should be given authority to hire competent salesmen, pay wages and incentives, allow concessions, within specified limits.

4. The subordinate must produce expected results from the task assigned to him – It is obligatory on the part of the subordinate that he must give satisfactory performance from the tasks assigned. He becomes answerable for the proper performance of the assigned duties and for the exercise of the delegated authority. Authority without accountability is likely to be misused.

Accountability without authority may be frustrating to the subordinates. The extent of accountability depends upon the extent of delegated authority and responsibility. A subordinate cannot be held responsible for acts not assigned to him by his superior. He is accountable only to his immediate superior.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

5. Proper evaluation of the performance must be made – In the end, information and control system must be established to check and evaluate the performance of the subordinates to whom authority has been delegated. Duties, authority and responsibility are the three interdependent essential steps in the process of delegation.

In this connection an eminent authority H. W. Newman has said – “These three inevitable attributes of delegation are like a three-legged stool, each depends on the others to support the whole and no two can stand alone.” What to delegate and when to delegate are two ticklish questions which a delegator has to answer to himself within the framework of the organization?

Process of Delegation – Assignment of Duties, Granting of Authority and Creation of Accountability

The process of delegation involves three steps as under:

1. Assignment of Duties or Responsibilities:

The process of delegation starts with dividing the work into suitable parts. The manager has to decide what part of work be performed by him and what part be transferred to his subordinates. He then, can assign the duties to subordinates indicating what he wants the subordinates to do.

Duties to be assigned should be determined in advance and should be clearly identified with the functions or tasks to be performed by the subordinates under delegated authority. Only such duties should be assigned as are within the physical or mental competence of the “delegate”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Granting of Authority:

While assigning duties the delegator grants authority to make use of men, materials, machines and money so that the assigned duties may be performed effectively.

Duties cannot be performed without grant of the necessary authority. So the subordinates should be given requisite authority such as use of resources, taking necessary action etc. to perform the given job.

3. Creation of Accountability or an Obligation:

Accountability is the obligation to carry out the responsibility with the help of authority in relation to the job entrusted and to report. The subordinate to whom authority is delegated is also made accountable for the proper performance of the job entrusted to him.

Delegation creates an obligation or responsibility on the part of the subordinate so that he is made accountable to the delegator -executive for the satisfactory performance of the duties assigned to him.

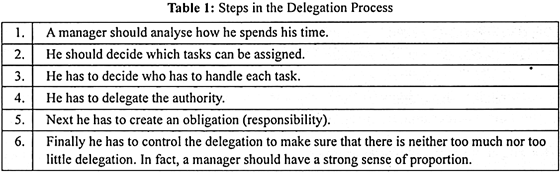

Process of Delegation – With Steps

To successfully delegate, a manager must decide which tasks can be delegated. Table 1 indicate the steps the manager can follow to analyse and improve the delegation process. In addition, clearly defining objectives and standards, involving subordinates in the delegation process, initiating training that defines and encourages delegation, and supporting control efforts tends to improve the overall delegation process.

Probably the most nebulous part of the delegation process enters around the question of how much authority to delegate. In truth, management must delegate sufficient authority to allow the subordinate to perform the job. Precisely what can and cannot be delegated depends on the commitments of the manager and the number and quality of subordinates. A rule of thumb is to delegate authority and responsibility to the lowest organisation level that has the competence to accept them.

Failure to master delegation is probably the single most frequently encountered reason managers fail. To be a good manager, a person must learn how to delegate effectively. The exception principle (also known as management by exception) states that managers should concentrate their efforts on matters that deviates too much from normal and allow its subordinates to handle routine matter.

Management by exception is an approach to management by making a decision which cannot be made or a problem which cannot be solved at one level is passed on to the higher one. The exception principle is closely related to the parity principle. The exception principle suggests that managers should concentrate on those matters which require their abilities and not become bogged down with duties their subordinates are supposed to do.

The exception principle can be hard to comply with when incompetent or insecure subordinates refer everything to their superiors because they are afraid to make a decision. On the other hand, superiors should refrain from making everyday decisions that they have delegated to subordinates. This problem is often referred to as – “micro-managing”.

Process of Delegation : 5 Essential Steps

According to Louis A. Allen, an executive can follow the following rules while delegating:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Establish goals that are to be attained.

2. Define and enumerate the authority which the delegatee can exercise and the responsibility he is to shoulder.

3. Motivate the subordinate and provide him sufficient guidance. If necessary, proper and adequate training should also be given to the delegatee before authority is delegated to him.

4. Ask for the completed work. During the course of work, if any help is needed by the delegatee, he should be provided with such help either directly or through someone who knows the work and is willing to help.

5. Establish an adequate control so as to supervise and provide necessary guidance.

The following steps are essential and they must be kept in mind while delegating:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. The delegation should clearly specify the expectations from his subordinates (delegate). Duties, authority and responsibility are the three interdependent essential steps in the process of delegation. According to H.W. Newman, “These three inevitable attributes of delegation are like a three legged stool, each depends on the others to support the whole and no two can stand alone.” What to delegate and when to delegate are two important questions which a delegator has to answer to himself within the framework of the organisation?

2. Based on the qualifications, experience and aptitude of the subordinates, duties should be assigned. They may be described either in terms of activity or in terms of results that are expected from the performance of activities.

3. Adequate authority shall be given to the subordinates. The superior confers upon the subordinate the right to act in a specified way within limited boundaries. It decides the actions which can be undertaken by a subordinate and actions which cannot be undertaken by him. Failure in conferring proper authority to any subordinate may deviate expected results.

4. The subordinate is required to give expected results from the work assigned to him. It is necessary on the part of the subordinate that he must give satisfactory performance from the tasks assigned. He is answerable for the proper performance of the assigned duties and for the exercise of the delegated authority. The extent of accountability depends is determined by delegated authority and responsibility.

A subordinate cannot be held responsible for acts not assigned to him by his superior. He is accountable only to his immediate superior and that too for the work assigned to him. Authority without accountability has no meaning. Likewise, accountability without authority may prove frustrating to the subordinates.

5. Proper evaluation of the performance must be made. The process of delegation is incomplete unless there is a system of information and control system to check and evaluate the performance of the subordinates to whom authority has been delegated.

Process of Delegation – (with Steps)

Normally the process of delegation involves four steps which are discussed as follows:

1. Preparation and Assignment of Tasks:

A well-formulated and prepared assignment when delegated is bound to fetch good results. The superior must therefore clearly establish the goals and objectives which specifies the purpose of delegating jobs. He decides on the jobs that he wants to be performed by his/her subordinates.

2. Transference of Power:

The superior must at this stage, grant proper authority to his/her subordinate so that the latter can carry out his/her assigned work without any difficulty.

3. Acceptance of Assignment:

At this stage, there are two options with the subordinate. He/She may either accept the assignment or may reject it. If the subordinate denies the job assigned to him/her along with the power, the superior has to find out his/her replacement who will willingly accept the assignment. The other option is when the subordinate accepts the assignment. Then the delegation process comes toward the end.

4. Accountability:

The circle gets complete once the subordinate accepts his/her assignment. He/She becomes accountable and answerable for the work that has been delegated to him/her by his/her superior and takes the responsibility of completing his/her task as per the agreed terms and conditions.

Process of Delegation – Top 4 Steps to Simplify the Process of Delegation

Delegation of authority is an essential technique of effective organisation. It acts as a happy ground for establishing superior-subordinates relationship. At the same time, it is a process, consisting of necessary steps or aspects. According to William H. Newman, the process of delegation has three aspects (steps)—(i) the assignment of duties, (ii) the granting of permission (authority), and (iii) the creation of an obligation (responsibility). It is important to note that the steps or aspects of the process of delegation are inter-related and inter- dependent.

In the words of Newman, “In theory at least, the three aspects of delegation are inseparable, and a change in any one of them normally implies a corresponding adjustment in the other two.”

However, in order to make the process of delegation simpler, it may be divided into the following four steps:

Step 1. Sub-Dividing the Work:

Sub-dividing the work or activities is the first step in the process of delegation of authority. For making the delegation effective, it is essential to subdivide the work to be delegated to the subordinates into meaningful groups. This helps in assessing the importance of each work group.

That is to say, this grouping of activities would facilitate to ascertain which work is strategically important and which one is of routine nature or which should be delegated to the subordinates and which should not. This, further, helps in ascertaining the amount of authority needed to perform a specific work or task. The sub-division of work for the purpose of delegation may vary from one organisation to another. On the basis of grouping the work, job description is possible.

Step 2. Assigning the Duties:

Assigning the duties to the subordinates by the superior is the second step in the process of delegation. The assignment of duties succeeds the sub-division of work. In the words of Theo Haimann, “In the assignment of duties the manager decides how the work is to be divided (distributed) among his subordinates. He will consider the best allocation of these duties in order to achieve a happy balance between an effective span of management and a reasonable number of managerial levels.”

In the process of assignment of duties a superior needs to consider the following main points:

i. Nature of job or duties.

ii. Availability of subordinates.

iii. Ability and skill of subordinates.

iv. Results expected.

v. Effect of delegation on organisation structure.

On the basis of above factors, a manager may decide which duties he can assign the subordinates and which cannot. To make the task of assignment of duties meaningful and successful, it is essential that subordinates must know what duties they have to perform and what results they have to produce or what goals they have to accomplish.

In this regard, Burt K. Scanlan has to say that the “assignment of responsibility (duty) phase of delegation is not quite as simple and academic as it might appear on the surface, and goes beyond what has been done by many managers historically.” He further states that “between a manager and each of his subordinates there must be a clear understanding and agreement as to –

i. The activities or task he is responsible for performing.

ii. The areas of his job where he is responsible or accountable for achieving results.

iii. The specific results he is accountable for achieving in each area.

iv. How performance in each area of accountability will be measured.”

The manner in which the duties are assigned to the subordinates depends upon the attitude of the superior or manager and his belief over the ability of his subordinates. In the words of Scanlan, “Effective delegation begins with the manager’s philosophy about people and their reaction to work.”

Step 3. Granting of Authority:

The next important step in the process of delegation is the granting of authority to the subordinates. According to Newman, the granting of authority refers to make commitments, use resources and take other actions necessary to perform the duties. In other words, the subordinates to whom duties are assigned must be granted adequate authority to carry the duties. In this process, it is essential for the manager to determine the extent of authority that is to be delegated to the subordinates. This further depends upon the area of authority the delegating manager himself possesses.

According to Theo Haimann, “Generally speaking, the wise manager will see to it that the scope of authority which is delegated to a subordinate is adequate for the successful performance of the assigned duties. But the scope should not be larger than necessary.”

In this regard, Peter F. Drucker has to say, “The manager has responsibility downward to his subordinate managers. He has to make sure they know and understand what is demanded of them. Then he has to help them reach these objectives. He is responsible for their getting the tools, the staff, the information they need. He has to help them with advice and counsel. He has, if need be, to teach them to do better.”

This reveals that granting of authority is a very important task for a superior. It does not simply mean that the subordinate be informed what is to be done, how it is to be done, when it is to be done, etc. But “it is a blending of two factors – a subordinate’s skills, abilities, knowledge and potential to contribute, and a manager’s guidance, counsel and help.” (Scanlan).

Step 4. Creating an Obligation:

This is the last step in the process of delegation. As a matter of fact, creating an obligation is the last product of delegation. Without it, there is no true delegation. Creating obligation refers to creating responsibility and accountability on the part of subordinates for the satisfactory performance of their assigned duties or tasks.

In the words of George Hall, “Act of delegation creates simultaneously, and without any further action or delegation, an accountability running from the individual receiving the delegation to the principal who made it. This accountability should be, by the act which creates it, of the same quality, quantity and weight as the accompanying responsibility and authority.” In fact, the subordinate, by accepting the authority and by responding to it, becomes the representative or delegate of the delegating manager.

Simultaneously, the subordinate assumes the obligation or responsibility to carry out the assignment and to account to the superior for the performance of his duties. If the subordinate does not accept the assignment, delegation is considered merely attempted and not made.

According to Newman, Summer and Warren, “By accepting an assignment, a subordinate, in effect, gives him promise to do his best in carrying out his duties. Having taken a job, he is morally bound to complete it. He can be held responsible for results.” It may further be concluded that by accepting an exercise of authority, the subordinate may reap several benefits, such as, recognition, reward, appreciation of his fellow workers, etc.

Process of Delegation – Three Aspects of Delegation

Newman succinctly points out that there are three chief aspects to the process of delegation of authority- (1) the assignment of duties by an executive to his immediate subordinates; (2) the granting of permission (authority) to make commitments, use resources, and take all actions which are necessary to perform the duties; and (3) the creation of an obligation (responsibility) on the part of each subordinate to the delegating exclusive to perform the duties satisfactorily.

These three aspects of delegation are inseparably interrelated, and change in one will require adjustment of the other two.

1. Assignment of Duties:

In the assignment of duties the manager decides how the work is to be divided among his subordinates. He will consider the best allocation of these duties in order to achieve a happy balance between an effective span of management and a reasonable number of managerial levels.

In checking his functions and duties the chief executive will examine them to see which he can delegate to others and which he cannot assign to a subordinate. There are some duties which are so routine that there is no doubt that the manager would do best to assign them to one of his subordinates.

There are other functions which he can delegate to subordinates who possess the necessary skill to perform them effectively. And then again there are those functions which he cannot delegate and must do himself. A number of managerial duties are borderline cases and could fall into either one of these groups.

Decisions as to whether or not the manager can allocate a specific duty to subordinate will often depend on the executive’s general attitude and the subordinates he has available.

2. The Granting of Authority:

The second aspect in the process of delegation is the granting of authority to make commitments, use resources, and to take the actions which are necessary to perform the allocated duties. To be specific, duties are assigned and authority is delegated not to people but to positions within the enterprise.

But unless these positions within the organization are manned by people, the assignments and the delegation of authority are meaningless. That is why one commonly speaks of the delegation of authority to subordinates instead of delegation of authority to subordinate positions.

In this stage the superior confers upon the subordinate the right to act and to decide within a limited area. It is necessary for the superior to determine the scope of authority which is to be delegated to the subordinate. This scope of necessity depends on the area of authority which the superior manager himself possesses.

The scope of authority is intrinsically related to the duties assigned to the subordinate, and any change in those will necessitate a change in the scope of authority. Generally speaking, the wise manager will see to it that the scope of authority which is delegated to a subordinate is adequate for the successful performance of the assigned duties. But the scope should not be larger than necessary.

It is obvious that clarity of the scope of authority of each subordinate manager is necessary for an organization in order to have clear and not fuzzy lines of authority. It is not enough that the clarity of the scope exists merely in the mind of the delegating executive.

The scope must be just as clear to the subordinate manager and to the minds of the other managers. Fuzziness can only lead to confusion, conflicts, and duplications of efforts.

3. Specific or General Delegation:

Delegation of authority can be specific or general, and it is obviously more desirable that it be specific. It often happens that a superior delegates authority in a broad sense to his subordinates. He merely tells them to take charge and to do whatever they deem necessary. This manner of delegation cannot be considered a satisfactory way to delegate authority.

It is much better to be precise and clear instead of letting the subordinate guess how far his authority may go. If the limits of his authority are clearly defined there will be no need for him to wonder how far it goes and to experiment by hit and miss. Therefore, it is advisable to be clear and specific as to the extent of the delegation of authority.

It is preferable, if appropriate, that the scope of authority be set down in writing for this will provide the subordinate with a clear guide at all times. Charts, manuals, and job descriptions will be of considerable aid in the manager’s endeavour to clarify the scope of authority.

Although the delegating manager has clearly written down the scope of authority, he has the obligation of checking from time to time to see whether or not the subordinate is keeping within the delegated limits.

He also should bear in mind that as conditions and circumstance change additional clarification and interpretations of the scope of authority might become necessary. This is primarily so if there should be a change in the assignment of duties.

On the other hand, there are times when the scope of authority cannot be made too specific. This is particularly true in a new enterprise or in some new venture within an existing organization.

It can happen that the superior himself does not fully realize how much is involved in a new activity, and he therefore cannot be specific as to the amount of authority he should be delegating to his subordinates. Because the extent of the new activity is not known, it is understandable that in such a case the delegation of authority cannot be specific.

But once the new task has begun to take shape, the subordinate would be wise to clarify his area of authority by discussing it with the superior or vice versa. By that time both know what is involved in the new activity.

Shared and Splintered Authority:

The superior may at sometime delegate authority to two or three subordinate together, for he may want the authority over a given situation to be hard by them. This is known as “shared authority”.

For example, the president of a corporation might want the vice-president in charge of production, the sales manager, and the chief engineer to share the authority of deciding which products will be carried in the product line for the coming year. In this instance, the three executives share the authority to make this decision. All three together have the authority.

In addition to the concept of shared authority, there is the concept of splintered authority which is frequently found in organizations. Splintered authority “exists wherever a problem cannot be solved or a decision made without pooling the authority delegations of two or more managers.” In this instance, the individual manager possesses all the authority he needs to make the decision within his own department.

However, the problem under consideration concerns a question which bridges more than one department. In order to solve this particular problem, the several managers pool their authority to make the decision. If it is necessary, however, for managers to pool their authority frequently, it is wise to re-examine the delegation of authority, checking to see whether or not some managers have been delegated too much or too little authority.

In checking into the varies applications of splintered authority, the superior manager would do well to find out whether or not such a pooling of splintered authority was applied to problems which, though not specifically included in the area of authority, still could be reasonably expected to fall within their level of the managerial hierarchy.

It is conceivable that several subordinate managers had pooled their authority in order to decide problems which the top manager wished to retain under his own authority and therefore had purposely not delegated. The author has had occasion to observe instances where the pooling of authority has led subordinate managers to make decisions on problems which the superior manager wanted clearly and specifically reserved for himself.

Following the exception principle, the problem should have been handled by referring it to the executive who is their common superior.

The Exception Principle:

The proper assignment of duties and the necessary scope of delegated authority will tell the subordinate manager the area within which he specifically alone is to make the decision. Should a problem come up which is beyond this scope, the subordinate manager must refer it upward in the organization.

He is to decide all those matters within his authority limitation, but he does not have authority over those which do not fall within this area. These exceptional problems must be referred upward; this is what is commonly known as the exception principle. Koontz calls it the authority-level principle.

There is great temptation to ignore this exception principle, but ignoring it will mean the weakening of the delegation of authority. There is a temptation for the incompetent and insecure subordinate to refer too many appeals and tool many “exceptions” to the superior. In such an instance, the superior manager should make it clearly understood that the problem is within the area of the subordinate’s decision-making power.

On the other hand, there is the temptation for the superior manager to make a decision concerning an activity where he once made the decision himself, but since he had delegated this authority and assigned the duties to a subordinate manager, he must refrain from deciding unless the problem brought to him is clearly an exception.

Process of Delegation – With Guidelines

The process of delegation involves:

(a) Assignment of tasks

(b) Delegation of authority for accomplishing the tasks

(c) Exaction of responsibility for accomplishment of the tasks

Delegation of authority, wherever possible, should be clearly documented as it then becomes extremely useful both to the one who receives it and the superior who delegates it. It enables the superior to isolate those decisions for which he can hold his subordinate responsible. However there are occasions when it is difficult to make delegation of authority specific.

This happens particularly in the case of new and developing jobs at top management cadres – at least in the beginning and till the work fully evolves. A minor argument against specific delegation is that it does not allow the subordinate the flexibility which could help him to develop in the best way.

There are situations where what we call splintered authority exists, where a problem cannot be solved alone and pooling of authority of one or more managers is necessary. For example, the superintendent of a steel melting shop thinks that he can reduce his cost by making minor changes in logistics of operations or modification in the procedures of the blast furnace department (where hot iron is produced for conversion to steel), where his authority cannot encompass the change.

However, the superintendents of both the steel melting shop and the blast furnace shop can agree upon the change if it does not affect any other equal or superior superintendent. Most of the present day managerial conferences are held because of the necessity of pooling authority to make decisions, and interdependence of working.

Delegation of authority is always subject to Withdrawal by the grantor. Even though the right to cover authority is unquestionable, it is generally not resorted to unless the need arises to modify enterprise objective, policies, organisation structure, etc. Reorganisation inevitably involves recovery and re-delegation of authority. Delegation of authority is generally extensive in decentralised organisations and limited in centralised organisations. Little or no delegation restricts the growth of the organisation and the number of managers.

Certain kinds of personal traits and attitude of the superior govern the extent of delegation.

Personal attitudes that favour delegation are:

(a) Receptiveness – to give others’ ideas a chance

(b) Willingness – to allow the subordinate to develop

(c) Willingness – to let others make occasional mistakes

(d) Willingness – to trust subordinates

(e) Willingness – to establish and use broad controls

Hazy or partial delegation, pseudo-delegation, delegation inconsistent with expected results, expectation that the subordinate must come to the superior for each decision – these are widely looked upon as weaknesses of delegation of authority by superior managers. On the other hand, subordinates who are weak in decision-making, who place too much reliance on spoon-feeding by superiors, untrained officers lacking in planning abilities or officers with lack of confidence in them seem to add to the problem of weak delegation.

The following are some of the practical guidelines for making delegation real and effective:

(i) Define assignments and delegate authority in the light of the results to be achieved.

(ii) Maintain open lines of communication.

(iii) Select the right man in view of the responsibility to be delegated.

(iv) Reward effective delegation and successful consumption of authority.

(v) Establish proper control for occasional checks to ensure that the authority delegated is not being misused and is being properly used.

Proper delegation helps in evolving a system. It is this system that works and personalities only assist the system.