Here is a compilation of notes on the principles of management:- 1. Definition of Management 2. Socio-Economic and Cultural Significance of Management 3. Organisation and Management 4. Nature 5. Dynamics 6. Managerial Acts 7. Process of Management 8. Challenge to Management 9. Theories of Management 10. Levels of Management 11. Management as an Art, a Science or a Profession and few other Notes.

Contents:

- Notes on the Definition of Management

- Notes on the Socio-Economic and Cultural Significance of Management

- Notes on the Organisation and Management

- Notes on the Nature of Management

- Notes on the Dynamics of Management

- Notes on the Managerial Acts

- Notes on the Process of Management

- Notes on the Challenges of Management

- Notes on the Theories of Management

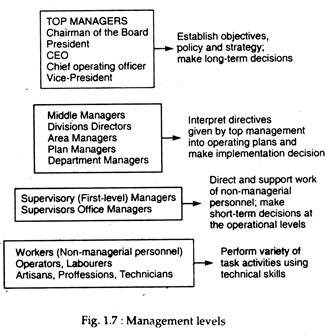

- Notes on the Levels of Management

- Notes on Management as an Art, a Science or a Profession

- Notes on Management as a Profession

- Notes on the Importance of Management

1. Notes on the Definition of Management:

Management is defined as the process of getting things done through the efforts of other people. This often involves the allocation and control of money and physical resources. A manager is not a manager if he works alone, i.e., unless involved in the process of getting things done through others.

Perhaps the most significant factor in determining the performance and process of any organisation is the quality of its management.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The job of managing is likely to become more and more challenging in the 21st century for a number of reasons – rapid growth of the service sector, foreign competition, large number of corporate mergers and acquisitions, restructurings, business process engineering, downsizing, flattening of the pyramid, empowerment and core competencies.

Although the study of mathematics started 5,000 years ago, that of economics 250 years ago, the study of management as a separate discipline is a comparatively recent event. The study of the subject started after the publication of F.W. Taylor’s influential book- Shop Management in 1903, which brought into focus the scientific character of the subject.

But the study of the subject, in the true sense, started with the publication of Peter Drucker’s Practice of Management in 1954. So, management is a young discipline. According to Drucker it is an art, rather than science. While science provides a framework of analysis, art follows certain practices. So, management as a subject has practical bias. It should be more concerned with practice than with theory.

There are many definitions of management. Henri Fayol, in the early twentieth century, defined it as the process of ‘forecasting, planning, organising, commanding, coordinating and controlling’. E. F. L. Brech called it ‘the social process of planning, coordination, control and motivation’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Writing in the 1980s, Tom Peters defined it as ‘organisational direction based on sound common sense, pride in the organisation and enthusiasm for its works’.

This definition is much broader than the one suggested by Drucker that management is a process. Management is more than a process.

As Richard Pettinger has rightly put it, “management is partly the process of getting things done through people; and partly the creative and energetic combination of scarce resources into effective and profitable activities, and the combination of the skill and talents of the individuals concerned with doing this”.

2. Notes on the Socio-Economic and Cultural Significance of Management:

Change in the economy pose both opportunities and problems for managers. In times of continual moderate growth, many organisations enjoy a growing demand for output, and funds are more easily available for plant expansion and other investments. However, when the economy shifts downward (as in a recession), demand plummets, unemployment rises and profits shrink.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Organisations must continually monitor changes in the chief economic indicators to minimise threats and capitalise on opportunities. Some organisations utilise projections of future economic conditions in making such decisions as whether to expand plant facilities or enter new markets.

However, leading economists often differ in their economic projections and many organisations are therefore skeptical about economic forecasting.

i. Political, Legal and Regulatory:

Numerous law$ and a multitude of authorities characterise the political, legal and regulatory forces in the external environment that have an indirect but strong influence on the organisation. More recent laws and judicial decisions have banned the use of polygraphs for employment decisions and restricted an organisation’s right to fire and its options in testing employees for drug use.

Most observers believe that government involvement in organisations will continue, given that people continue to call on government to protect the consumer, preserve the environments and push for an end to discrimination in employment, education and housing. Consequently, many organisations monitor governmental and legislative developments to ensure their own compliance with the law.

ii. Cultural and Social:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Cultural and social forces are changes in our social and cultural system that can affect an organisation’s actions and the demand for its products or services. Every nation has a social and cultural system comprising certain beliefs and values.

Environmental interest groups have lobbied for legislation to further limit industries emissions of fossil fuels (gas, coal and oil) that intensify the greenhouse effect — a phenomenon that could produce disastrous changes in the world’s climate.

Organisations should monitor social and cultural forces because these external forces are extremely important to their performance. Interestingly, however, many organisations ignore the potential effects of these indirect forces until they become direct forces. To avoid complacency, managers can adopt principles that commit their organisations to actions defined by society as in accordance with good citizenship.

This heightened sense of concern for the environment has produced a heated debate among all those who have an interest in the environment and that includes nearly everyone with an awareness of world events. Considerable sentiment abounds that organisations must take greater safeguards to protect the environment.

3. Notes on the Organisation and Management:

Management is conducted within an organisational framework or within organisations. Organisation may be treated as the context of management. D. S. Pugh describes management as ‘systems of interdependent human beings’. Nobel Laureate H. A. Simon has defined it as a ‘joint function of human characteristics, the task to be accomplished and its environment’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At different stages of our study we will find that organisations are combinations of resources brought together for a purpose; according to a modern theory — called biological theory — organisations have a life and a permanent identity of their own, and are energized by people.

a. The Concept of Organisation:

At different phases of our lives, each of us is associated with some kind of organisation — a college, a football club, a musical group, a hospital or a business. These organisations do differ from one another in more ways that one. Some, like a giant corporation like General Motors, or the army, may be organised very formally.

Others, like a local football team in a particular locality, may be less formally organised. But irrespective of their differences, all the organisations of which each of us is a member have some basic common features.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The most common element of an organisation seems to be a goal or a purpose. The goals do differ — to win a trophy, to entertain an audience, or to sell a product profitably. But without a goal an organisation will cease to exist. These organisations will also have some programme or method for achieving their goals — to win a certain number of games, to manufacture and advertise a profitable product.

Without a clear idea of what it must do, an organisation is not likely to be effective. Finally, an organisation must be endowed with leaders, managers responsible for helping organisations achieve their goals. In some organisations it is very easy to identify the leader(s).

In others, who the leaders actually are probably will not be that obvious. But an organisation without a manager is like a ship without a rudder. It will have no clear direction.

Any modern society is influenced by managers and their organisations. The term ‘organisation’ is defined as a group of two or more people working together in predetermined fashion to attain a set of goals such as profits, the discovery of knowledge, national defence, or social welfare (managing a charitable trust or dispensary). Different types of organisations pervade our society.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The objective of this title is to bring into focus an important issue: how organisations are managed or, more specifically, how managers can best help their organisations set and achieve their goals.

The stress will be on the so-called formal organisations such as business firms (especially the corporate forms of organisation), hospitals, charitable trusts or religious goods or services to their customers or clients and offer career opportunities to their members.

It is easier to discuss the management of formal organisations for the simple reason that people in such organisations do have certain well-defined responsibilities. Furthermore, in such organisations, the role of the manager will be clear-cut and directly visible.

In fact, whatever be the role of the manager and how formal it may be, all managers in all organisations have the same basic responsibility: to help other members of the organisation set and reach a set of objectives and goals. The major purpose of this title is to enable the reader understand how managers accomplish this task.

b. Defining Management:

Management is basically concerned with ideas, things and people. Since the study of management involves people it is very difficult to define the term ‘management’. In fact, there are various definitions of management. But none has been universally accepted. Fredrick W. Taylor probably first suggested a definition of management.

According to him management is “Knowing exactly what you want (people) to do, and then seeing that they do it in the best and cheapest way”. As we will see throughout this text, however, management is actually a very complex process — much more complex than this definition would seem to suggest. Thus, we have to develop a definition of management that better captures the true nature of the process.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Mary Parker Follett has suggested a simple definition which is very popular. According to her, management is “the art (process) of getting things done through people”. The implication of this definition is simple enough- managers strive to attain their goals “by arranging for others to perform whatever tasks are necessary — not by performing the tasks themselves”.

Management is the use of people and other resources to accomplish organisational objectives.

William F. Glueck has suggested a slightly different definition. According to him, “management is effective utilisation of human and material resources to achieve enterprises’ objectives”.

So management is a (difficult term to define. It has a variety of interpretations and applications — all correct within a given set of parameters.

In the words of L. F. Boone and D. L. Kurtz- “Sometimes it is used to describe the executives and administrators of an organisation, as when one talks of labour-management negotiations. In other cases, it suggests the professional career path aspired to by most business administration students. And, in still other cases, it refers to a system for getting things done”.

H. Koontz and C. Odonell, however, follow a system-type definition. According to them, management is the use of people and other resources to accomplish organisational objectives. This definition is universally applicable, i.e., applicable to all organisational structures, both profit-oriented and not-for-profit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In fact, the process of management is as important to the functioning of Calcutta Medical College or a fire department as it is of Tata Iron and Steel Company.

c. Systems Theory:

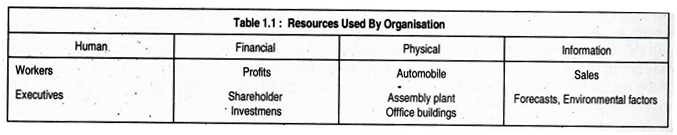

Management is perhaps best understood if we apply systems theory. According to systems theory, a modern organisation utilises four basic kinds of resources which are acquired from the environment: human, monetary, physical and information.

Human resources include labour service, entrepreneurial ability, managerial talent and so forth. Monetary resources are the financial capital used by an organisation to carry on its day-to-day functions as also for its long-term operations. Physical resources include raw materials, production facilities, office building, as also machinery and equipment.

Information resources refer to all type of data needed to make effective decisions. Examples of resources used in a typical manufacturing organisation are listed in Table 1.1.

The manager’s job involves combining and coordinating these various resources to achieve the goals of the organisation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A manager at Hindustan Motors Ltd., for example, uses the talents of executives and automobile assembly plant workers, profits set aside for reinvestment, existing factory and office premises, and sales forecasts to make decisions regarding the number of cars to be produced and distributed during the next quarter.

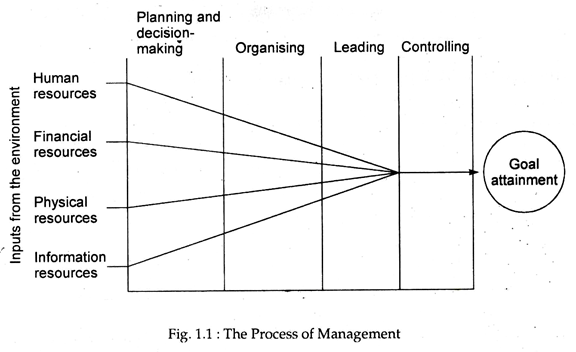

How do managers go about combining and coordinating the various kinds of resources? They do it by carrying out four basic managerial functions: planning and decision making, organising, leading and controlling.

So management is a process — a process of combining inputs acquired from the environment to attain organisation goal(s) by performing certain functions.

This point is illustrated in Fig. 1.1 which enables us to suggest the following definition:

Management is essentially the process of planning and decision-making, organising, leading and controlling an organisation’s human, financial, physical and information resources with a view to attaining organisational goals in the best possible way, i.e., in an efficient and effective manner.

d. Efficiency v. Effectiveness:

This very definition enables us to identify the basic purpose of management — to ensure an organisation’s goals in an efficient and effective manner. By efficient, we mean doing things in a systematic fashion without unnecessary waste. For example, a firm that produces quality products at the lowest possible cost and distributes them with minimum transportation charges is efficient.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

By effective, we mean doing things right. A firm could produce manual calculators or regular wrist- watches very efficiently but still not succeed. As a general rule, successful management involves being both efficient and effective.

e. Who is a Manager?

We may now suggest a definition of management in this context. A manager is someone whose primary activities are part of the management process. To be more explicit, a manager is someone who plans and makes decisions, organises, leads, controls all the four resources of an organisation — human, financial, physical and information.

f. The Management Process:

An useful way to illustrate the various aspects of the management process is to describe how it works in a modern organisation. In an actual organisation, a manager to be successful has to spend a lot of the planning organisation’s various activities and programmes and making decisions about how various things would be done.

He then designs an appropriate organisation for producing and marketing the company’s products (and services). Then the manager has to play a strong leadership role in first selecting the right people for the firm and then motivating them to work both efficiently and effectively. And throughout the entire process, he imposes an appropriate control system to optimise the use of all the four resources.

So, we have identified four stages in the management process. Each of the key management processes contribute to the success of an enterprise. However, the above four phases of the management process do not actually work in a tidy, step-by-step fashion.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At a fixed point of time, a manager is likely to be engaged in several different activities simultaneously. In the real commercial world, as many differences as similarities exist in management work from one setting to another — the similarities are the phases in the management process; the differences relate to the emphasis, sequencing, and implications of each.

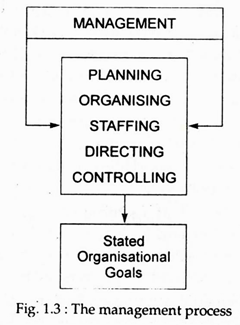

J. A. F. Stoner has suggested is a more elaborate definition of management on the basis of managerial functions. His definition; “Managing is the process of planning, organising, leading and controlling the efforts of organisational members and the use of other organisational resources in order to achieve stated organisational goals”.

It is clear that Stoner has used the word ‘process’ rather than ‘art’ in defining management. As Stoner argue: “To say that management is an art implies that it is personal attitude or skill. A process, on the other hand, is nothing more than a systematic way of doing things. All managers, regardless of their particular attitude or skills, engage in certain interrelated activities in order to achieve their desired goal”.

Stoner has called the management activities planning, organising, leading (directing) and controlling. In fact, management is a distinct process, consisting of planning, organising, actuating and controlling performance to determine and accomplish objectives by the use of people and resources.

Others have added one more function, viz., staffing, to the list:

1. Planning and Decision Making: Determining Courses of Action:

A plan is a statement of things to be done and the sequence and timing in which they should be done in order to achieve a given end. In its simplest form, planning means determining the goals of an organisation and deciding how best to achieve them.

Decision-making, a part of the planning process, involves selecting a course from various alternatives that are available. Planning involves deciding aims and objectives, selecting the correct strategies and programmes to achieve the aims, determining and allocating the resources required and ensuring that plans are communicated to all concerned.

As Stoner puts it:

“Planning means that managers think their actions through in advance. Their actions are usually based on some method, or logic, rather than on a hunch”.

Planning and decision-making help maintain managerial effectiveness by serving as guides for future activities. Top management at Reliance Industries, for example, might establish a goal of increasing by 10% of its share of textiles market by 2004. To attain this goal, managers could develop plans to increase the advertising budget, expand the product line, and improve the mix of distributor incentives.

These goals and methods would then serve as the planning framework for the textile plant of Reliance.

There are various steps in planning. The first basic step in a planning exercise is to establish goals that define an expected or desired future state. Within the context of one or more important goals, the manager might also set various sub-goals, or objectives.

If Reliance is really serious about increasing its market share by 10% in 2004, managers might decide that the increase would come, in increments of 2% per year, beginning in 1999.

Ascertaining where he (she) wants the organisation to be at a given time in the future, the manager next develops a strategy for getting these. This development process is known as strategic planning. After developing the strategic plans, the manager has to implement then in the next step, i.e., he has to put them into effect.

In short, specifying where the organisation is to go and how it is to go there involves making a number of crucial (strategic) decisions and many more have to be made along the way.

2. Organising: Co-ordinating Resources and Activities:

Once a manager has developed a workable plan, the next phase of management is to organise the human and other resources necessary to carry out the plan. A very simple example will make the point clear. Suppose an individual has a Rs 1,20,000 budget and four subordinates to execute a plan. Perhaps the simplest approach might involve giving each subordinate a Rs 30,000 budget and having each one report to him.

An alternative method might be to establish one of them as a supervisor of the other three, who would have budgets of Rs 40,000 each. Determining the best method for grouping activities and resources in the overall interest of the organisation is the organising process.

The term ‘organisation’ refers to sub-division and delegation of the overall management task by allocating responsibility and authority to carry out defined work and by defining the relationships that should exist among different functions and positions.

Organising means that managers co-ordinate human and material resources of the organisation properly so as to achieve organisational goals. The strength of an organisation largely depends on its ability to marshall various human and non-human resources to attain a goal.

It is obvious that the more integrated and coordinated the work of an organisation, the more effective it is likely to be. It is the job of the manager to achieve this co-ordination.

The basic elements of organising are work specialisation, departmentalisation, authority relationships, spans of control, and line and staff roles.

In this context, we have to do three things:

(i) To discuss different ways of getting work in organisations (such as staffing, designing jobs, establishing work schedules, using committees and the management of conflict);

(ii) To explain how all these various elements and concepts fit together to form an overall organisation structure or design; and

(iii) To highlight the importance as also the problems associated with organisational change and development (i.e., various strategies, approaches and techniques for changing organisational elements and processes).

3. Leading: Motivating and Managing Employees:

Once the organisation process is complete, different people are to be given different assignments and put at appropriate places. But the job of the manager does not end here. Rather, it is the beginning of the hardest part of the management process — leading. Leading is the set of processes used to get members of the organisation to work together to further the interests of the organisation.

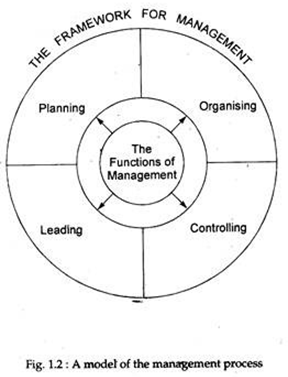

Leading (directing) means that managers direct and influence the ‘activities’ of subordinates. It is not the task of managers to give orders, but to create proper atmosphere so as to help subordinates to their best. In fact, managers do not act alone. Rather they get others to perform essential tasks. Fig. 1.2 is a model of the managerial process that is based on four major functions of the management.

3A. Four Sub-functions:

The leading function consists of four different activities. One is motivating people to put as much effort as they can. This activity is the essence of the whole leading process. It involves giving employees the opportunity to attain individual goals and rewards through their performance on the job.

A second aspect of leading is leadership itself. The basic focus of this activity is on what the manager does to encourage organisational performance (rather than on management activities directed toward fulfilling employee needs and expectations).

The third part of the leading function has to do with groups and group process. An inherent part of the organising process is the initial creation of groups in a company. However, once this activity is over, the manager has to deal with groups, i.e., with both group members and group activities, on an ongoing basis, from an interpersonal perspective.

The fourth and final component of leading is communication, not communication for its own sake, but communication with a purpose, i.e., achievement of organisational goals.

4. Staffing: Putting the Right People at the Right Place:

Staffing is designed to assess the abilities and potential of employees and how far these measure up to the company’s or organisation’s needs. It is concerned with recruitment, or, selection of the right type of people as also proper manpower planning, it is also concerned with job evaluation and merit rating (performance appraisal).

5. Controlling: Monitoring and Evaluating Activities:

The final phase of the management process is controlling. As the organisation moves toward its goal, management must monitor its progress. It must make sure that the organisation is performing in such a way as to arrive at its ‘destination’ within the specified time period. If there is any deviation from the path it has to be corrected as soon as possible. This monitoring and corrective function is known as controlling.

The term controlling refers to the process of measuring and monitoring actual performance in companies with pre-determined objectives, plans, standards and budgets and taking any corrective action required.

In the words of Stoner:

“Controlling means that managers attempt to ensure that the organisation is moving toward its goals.

If some part of their organisation is on the wrong track, managers try to find out its cause and set things right”. Controlling helps ensure the effectiveness and efficiency needed for successful management.

Stoner’s definition indicates that managers use all the resources of the organisation—its finances, equipment and information as well its people — in attaining the goals of the organisation. No doubt, people are the most important resource of an organisation. But manages must also rely on other resources available to them to achieve the best possible results.

For example, a marketing manager, whose objective is to increase sales, must not only motivate the sale force but also spend huge amount of money on advertising and sales promotion.

It is in this context that the following definition becomes relevant:

“Management is the process of acquiring and combining human, financial, and physical resources to attain the organisation’s primary goal of producing a product or service desired by some segment of society”.

The process is essential to the functioning of all types of organisations — profit and non-profit; the necessary resources (human and material) must be acquired and combined in some way to produce a useful goods or to generate a valuable service. The general process in the manufacture of a motor car, an audit of accounting records, the insurance of a government regulation, or the education of student.

The manager provides “the dynamic forces or direction necessary to acquire and combine static resources into a functioning, productive organisation. He or she is the individual in charge and is expected to get results and to see that things happen as they should”.

Finally, we may note that management involves achieving the ‘stated goals’ of the organisation. The implication is that managers of any organisation — be a profit-seeking firm, a hospital, a government department or a sports club — must try to attain specific ends. These ends, of course, do vary from organisation to organisation.

But management is the process by which the goals are (sought to be) achieved. See Fig. 1.3 which is self-explanatory.

The Most Accepted One:

Perhaps the most widely accepted definition of management is the following one suggested by H. Koontz and C. O’donnel- “The creation and maintenance of an internal environment in an enterprise where individuals, working together in groups, can perform efficiently and effectively towards the attainment of group goals. Management could, then, be called ‘performance of environment design’. Essentially, managing is the art of doing, and management is the body of organised knowledge which underlies the art”.

It is often believed that our productive output is the result of effective management — management which so combines the inputs (i.e., the factors of production loosely) and coordinates their activities that they are judiciously and optimally used to produce and distribute the desirable goods and services.

To sum up, there are five basic functions of management: planning and decision-making, organising, leading (directing), staffing and controlling.

However, from our real life we see that every activity we undertake involves an element that ensures coordination and cohesiveness to the activity, without which our acts would be random, stumbling, unproductive and, thus, ineffective. The element that infuses plan and objective, as well as cohesion, into our activities is called management.

4. Notes on the Nature of Management:

Management is both a simple and a complex activity. In other words, its intensity (complexity) varies with and depends on circumstances. Managing a small single-owner firm is not the same thing as managing a giant multinational company like Union Carbide or ITC Ltd.

Management in a simple undertaking may simply encompass such activities as receiving, sorting (remembering), translating and communicating information.

In such an organisation, the manager who directs the efforts of a labourer who loads a certain article, say radio or pressure cooker, into a lorry, may just instruct the loader what needs to be loaded, how it should be packed and direct how it should be unloaded once the lorry reaches its destination.

To the manager of an organisation, the basic task is to see what needs to be done and to tell his men what to do. There management consists of getting things done through others; a manager is one who accomplishes objectives by directing the efforts of others.

Contrarily, some organisations are complex in structure. Managing these may require skills other than just issuing verbal orders. It may necessitate technical knowledge and skills, a wide perception of the international market and world demand and an understanding of the business environment in which the company operates and a clear thinking of the decisions affecting the outcome of the operations made.

Top management — be it the chief executive of a company or president of a large firm or head of a government undertaking — will have to take note of these realities irrespective of the organisational framework.

Decision-Making:

Management is essentially a decision-making process, and to manage well a manager has to take the right decision at the right time. As management becomes more and more technical and complex the volume of decision-making increases proportionately, or more than proportionately, in some cases.

Furthermore, if one accepts that there is a limit to the number of people an executive can deal with, rather exclusively, it is essential that decision-making is properly shared. Broadly, decisions are of two kinds: policy-decisions and crisis decisions.

In normal running of a business there are crisis decisions. The crisis point is simply emphasised to underscore the point that top management should not allow itself to go off the track.

Decisions vary in the way they commit an undertaking in the future and in the number of people they affect. As production, marketing and financial techniques improve, policy-decisions become increasingly separated from crisis-decisions simply because larger amount of rationality and empiricism enters into the decision-making process. Management, in a word, becomes more analytical and less intuitive.

Says R. Falk – “Management is largely a question of decision, and decisions cannot properly be taken unless the mind is clear about objectives and priorities, to achieve that clarity of mind calls for a form of concentration which is in itself a vital discipline. Confused orders and delayed actions are signs of a management that is incapable of decisive thought.”

Management is an integrated as well as a continuous process. Every industrial or commercial organisation requires the making of decisions, the coordination of diverse as well as interrelated activities, the handling of people and the evaluation of performance directed towards group objectives or goals.

A quote to drive home the point:

“The chief characteristic of management is the integration and application of the knowledge and analytical approaches developed by numerous disciplines. The manager’s problem is to seek a balance among these special approaches and to apply the pertinent concepts in specific situations which require action.”

A manager must, of necessity, evolve a systems approach which should encompass the total and integrated aspects of the entire organisation.

5. Notes on the Dynamics of Management:

In today’s changing world — characterised by growing competition, technological change which is giving birth to new products and processes, shifts of demand from one product to another due to population growth, changes in tastes and preferences and mass (competitive) advertising, changes in socioeconomic environment, the growing complexities of human relationships, specialization of labour and increase in the scale of operations — management has become a complex and a challenging affair in any business concern. The dynamics of it should necessarily be the characteristic of any study of its theory and practice.

In general, the word management implies identifying a special group of people whose job is to direct effort towards common objectives through the activities of other people. In simple terms, it means ‘getting things done through others’.

Massie defines it as “the process by which a cooperative group directs actions toward common goals. This process involves techniques by which a distinguishable group of people (managers) co-ordinates activities themselves. This process consists of certain basic functions.”

6. Notes on the Managerial Acts:

The list of function of a manager is a big one and can hardly be made exhaustive.

Yet, in a nutshell, it may be said that a manager —

(a) Talks to employees,

(b) Gives directions to supervisors,

(c) Dictates letters,

(d) Establishes production goals,

(e) Reads communications, reports, etc.,

(f) Attends committee meetings,

(g) Makes decisions about new projects,

(h) Plans what he will do about new building,

(i) Decides whom to promote, and so on.

The activities thus listed and professionally undertaken by a manager are either physical or mental in nature. The physical activities came under the broad concept of communication. The manager is either communicating something in writing, over the telephone, by gesture, etc., or he is receiving a communication from others — written or verbal. These activities can be observed directly.

Certainly, mental activities are not directly observable. However, one knows through his communication that he thinks and makes decisions. Decision-making is basically a mental activity and belief about it must be created among the persons concerned.

To quote C. S. George, Jr. “The ultimate objective of these managerial acts is to create an environment in which individuals will willingly participate in order to achieve objectives. In fact, this is the total job of a manager- to create an environment conducive to the performance of acts of other individuals (1) to achieve a collective goal (commonly called the firm’s goal), and (2) to achieve one or more of the goals of the participating individuals.”

In other words, what is demanded of a manager is that he creates a work-atmosphere that will encourage and enthuse people to lend their efforts and participate in activity in the undertaking. In fact, if such an environment is not created, employees will be reluctant to join him in accomplishing the desired tasks.

7. Notes on the Process of Management:

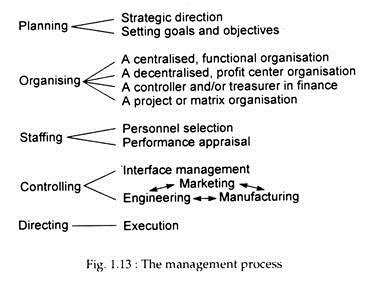

The process of management can be analysed by describing the various functions performed by management. Fig. 1.13 shows some aspects of the various managerial functions.

I. Planning:

In an uncertain world every manager must, to a considerable extent, make plans for the future in order to avoid uncertainty by adopting certain safeguards against it.

(a) Short-and Long-term Plans:

Plans are of two types: short-and long-run. Short-run plans are basically concerned with the efficient use of scarce (eisting) resources of a firm. Contrarily, long-run plans may encompass such things as the provision for new physical resources as short-run plans.

Moreover, the crucial factor that extends the range of planning is uncertainty.

Says Thomas Kempner- “All forecasts are inaccurate. Since plans are based on forecasts and since plans must be prepared with these possible errors in mind the greater the range of the plan more seriously will these errors have to be considered by the planner”.

(b) Corporate or Strategic Planning:

Every business manager will have to plan for the future to some extent. Company planning goes under the name corporate planning or strategic planning.

For example, a manager must — today or tomorrow — decide-what products should be produced and when and in which quantities — now and in the near future — and decide upon the company’s growth pattern and modernisation, expansion and diversification programmes during the next few years.

“These and similar looking-ahead activities we call planning, a vital function performed by every manager Planning in this manner, therefore, is a rational, economic and systematic way of making decisions today which will affect the future”.

In the words of Stoner “Plans are needed to give the organisation its goals and to set up the best procedure for reaching them”.

Moreover, “plans permit (1) the organisation to set aside the resources it will need for required activities, (2) members of organisation to carry on activities consistent with the chosen procedures, and (3) the progress toward the objectives to be monitored and measured, so that corrective action can be taken if the rate of progress is unsatisfactory”.

The practice of corporate planning is now established on a worldwide basis and it continues to grow rapidly. The interest in planning stems from the fact, in some situations that management and planning are virtually synonymous. Various benefits can be derived from a formal approach to planning.

It forces a manager to think forward and anticipate problems in advance much before they occur. It provides a detailed forecast. This enables the business manager to eliminate uncertainty regarding the future and thus take rational decision on the basis of such forecast.

Moreover, detailed planning enables a manager to delegate with more confidence. Within the overall framework of corporate plan, a subordinate can be given a fair amount of autonomy and independence, while his superior, on the other hand, retains general control.

Planning may, therefore, be treated as a natural part of the management process. Corporate planning, however, lays stress on a regular review of strategy. It refers to ‘planning systematically the total resources of the company for the achievement of quantified objectives within the relation of corporate planning to strategy. Peter Drucker’s definition is, therefore, preferable.

He defines corporate long-range planning as ‘a continuous process of making entrepreneurial decisions systematically and with the best possible knowledge of their futurity; organising systematically the result against expectations through organised systematic feedback’. In short, corporate planning is nothing other than a systematic approach to strategic decision making.

Benefits of Planning:

Companies, while introducing corporate planning, foresee the following benefits:

1. To improve coordination between divisions.

2. To achieve successful diversification.

3. To ensure a rational allocation of resources.

4. To anticipate technological changes.

Steps in Planning:

Various steps are involved in planning:

1. The first step involves the selection of organisational goals.

2. The second step consists of establishing goals for various divisions and departments within the organisation.

3. After deciding upon the goals, in the next step programmes are established for achieving them in a systematic manner.

However, in selecting the goals and developing the programmes the manager must examine their feasibility and whether they should be acceptable to the organisation’s managers and employees.

Duration and Size of Plans:

Plans made by top management for the whole organisation may cover a time period of five to ten years. In giant corporations, such plans may involve commitments of crores of rupees. However, planners at the lower levels, and middle level (or first line) managers may cover much shorter period and involve lesser amounts.

For example, such plans may be just for the next day’s work or for a three-hour meeting to take place once a month or week.

In short, “the planning phase consists of looking ahead, providing a strategic direction to the firm in terms of the business in which the firm chooses to be engaged and setting appropriate goals and objectives. Strategic planning must be followed by a detailed operational planning system which enhances the likelihood that the firm’s operating units will achieve the desired results”.

II. Organising:

After establishing objectives and developing plans or programmes to reach, managers have to design and develop an organisation that will enable them to carry out those programmes successfully. There is need for different types of organisations to achieve different objectives.

For example, manufacturing motor cars requires assembly-line techniques, while publishing this book on management requires teams of professionals — author, editor, printer, artist, binder and so on. So the main point is that “managers must have the ability to determine what types of organisation will be needed to accomplish a given set of objectives”.

And they must have the ability to develop (and later to lead) that type of organisation.

Organising is the process by which the structure and allocation of jobs are determined. It is widely recognised that a manager must organise — organise people, organise materials, organise jobs, organise time. Through this process he brings order out of chaos and introduces his system into an environment which is likely to be conducive to achieving the organisational goals and objectives.

Organising consists of three things:

(1) Determining what activities need to be done to fulfill the goals of the firm,

(2) Grouping and-assigning these activities to subordinates and

(3) Delegating the necessary authority to the subordinates to carry out the activities in a coherent (or rather coordinated) manner.

A quote from C. S. George again- “When a manager directs work, establishes goals and fixes authority relationships, he is obviously performing the organising function in addition to the function of planning”.

Ten Commandments of Good Organisation:

The Ten Commandments of Good Organisation were formulated by M. C. Rorty, former Vice-president of International Telegraph Corporation, immediately after he became the president of the American Management Association in 1934.

These are:

(i) Definite and clear-cut responsibilities should be assigned to each executive manager supervisor and foreman.

(ii) Responsibility should always be coupled with corresponding authority.

(iii) No change should be made in the scope or responsibility of a position without a definite understanding to that effect on the part of all persons concerned.

(iv) No executive or employee occupying a single position in the organisation should be subject to definite orders from more than one source.

(v) Orders should never be given to subordinates over the head of a responsible executive. Rather than do this, the officer in question should be supplanted.

(vi) Criticisms of subordinates should be precise. In no case should a subordinate be criticized in the presence of executives or employees of equal or lower rank.

(vii) Promotions, wage changes and disciplinary action should always be approved of by the executive immediately superior to the one directly responsible.

(viii) No executive or employee should be assistant to and at the same time a critic of the person he is assistant to.

(ix) Any executive whose work is subject to regular inspection should, whenever practicable, be given the assistance and facilities necessary to enable him to maintain an independent check on the quality of his work.

III. Staffing:

Writers on organisation often consider staffing an organisation to be a part of the organising function. The term ‘staffing’ refers to the recruitment and placement of the qualified personnel needed to do the organisation’s works.

The manager must appoint personnel to manage the organisational activities created and must continually appraise their performance relative to agreed upon goals and objectives. Some management experts, however, hold a different view. They list staffing as a separate management function or consider it to be a part of the leadership function.

Staffing refers to the process by which managers select, train, promote and retire subordinates. In organising, as we have noticed, the manager establishes positions and decides which duties and responsibilities properly belong to each one. In staffing, he tries to locate the right man for each job.

In fact, both organising and staffing are continuous functions “since changes in plans and objectives will often require changes in the organisation and occasionally necessitate a complete re-organisation. And staffing obviously cannot be done once and for all, since people are continually leaving, getting fired, retiring and dying. Often, too, changes in the organisation create new positions and these must be filled”.

IV. Directing (Leading):

After making the plans and establishing the organisation and staffing it, the manager has to move toward the declared objectives of the organisation. This function goes by various names: ‘leading’, ‘directing’, ‘motivating’ or ‘actuating’. A manager has to actuate personnel to the degree that behaviour is consistent and congruent with that perceived as necessary for accomplishing organisational goals.

In this sense actuation includes motivation, leadership, communication, training and personal influence. As such, this function is often discussed as directing and executing the work that must be done. In addition, while providing direction for behaviour, actuating becomes closely interrelated with the other functions of planning, organising and controlling.

The basic function involves ‘getting the members of the organisation to perform in ways that will help it achieves the established objectives’. This entails monitoring numerous details on a continuous basis in a timely and effective manner.

A related point may be noted in this context. Planning and organising functions do focus, at least partly, on more abstract aspects of the management process. On the contrary, the activity of leading focuses directly on the organisational people.

In short, leading refers to the process by which actual performance of subordinates is guided towards common goals. In an uncertain world no one can predict with precision what problems and opportunities will arise in daily work. It is therefore necessary for the manager to get some guidelines for action and provide day-to-day direction for his subordinates.

This managerial function, in fact, consists of those activities that deal directly with influencing, guiding, or supervising subordinates in their jobs. A good manager must ensure that his subordinates know the results he expects in each situation, help them to improve their skills and, on occasions, tell them exactly how and when to perform the needed tasks.

In other words, he must make his subordinates feel that they, too, apply themselves fully, not merely work well enough to get by.

V. Controlling:

Finally, an important task of the manager is to ensure that the actions of the people in the organisation do in fact move the organisation towards the stated goals. This is the control function of management and involves comparing results to plans and taking appropriate action.

Earlier we have noted that controlling refers to the process of measuring and monitoring actual performance in comparison with predetermined objectives, plans, standards and budgets and taking any corrective action required.

It involves the following three elements:

1. Establishing standards of performance;

2. Measuring current performance and comparing it against the established standards; and

3. Taking action to correct any performance that does not meet those standards.

By performing the controlling function, the manager can keep the organisation on the right track before it markedly deviates from its goals.

Basically, controlling is the process that measures-current performance and guides it towards some predetermined goal. In directing, the manager explains to his subordinates what they are to do and helps them do it to the best of their ability.

In controlling, he determines how well the pre-fixed jobs are being performed and what progress is being made towards the goals. He must know what is going on so that he can intervene and make necessary changes as and when, the organisational performance deviates from the path, i.e., from the optimum he has set for it.

Controlling is necessary for various reasons. Orders may be misunderstood and misinterpreted, rules may be violated and objectives may shift unknowingly. In fact, the larger the organisation the more complex is its structure and more the people involved in it, the greater are the probabilities that inappropriate action (or inaction) will be taken. Control is necessary to correct the deviation from a norm or plan.

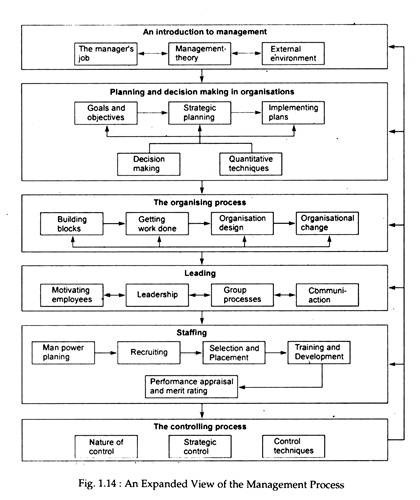

Fig. 1.14 gives an expanded view of the management process.

Control through reporting and budgetary control:

Gulick’s reporting is just a means of control rather than a separate function. Reports are made in such a fashion that the manager, his superiors or his subordinates may have a look at what is happening and, in case of necessity, may change their courses of action.

Similarly, controls are exercised through the budget. This is known as budgetary control. In fact, “budget is not only a plan. It is a means of control, too. If there is budget overrun, the organisation is spending more for something than it had planned. This means that some adjustment must be made somewhere to compensate for this”.

It may be noted that for exercising control there is often need for an adjustment in plans. In fact, all the five functions discussed above are closely interrelated.

Coordinating — the Essence of Management:

When two or more individuals work together to achieve a common goal, coordination is required to blend the efforts of all members for an efficient and effective result. Thus, coordination is not considered a basic management function, but is the result of interplay among the other functions.

Some authorities consider coordination to be a separate function of management. Henri Fayol and others are of this view. However, since coordination is present at all layers of the management process and permeate all stages of the management function; it is in the rightness of things to consider coordination as an overall function or the essence of management.

Any organisation involves the division of a total task into subtasks. It also involves the reunification of the various divisions to form an integrated whole. At any point in a management situation the need to coordinate functions is essential.

An organisation chart can indicate the way and a complex network of committees can be organised. But these will be ineffective if the management posts are Med by men and women who fail to understand the basic fact that responsibility, to be effective, must be shared.

The extent to which coordination will become a problem depends on a host of factors, notably the degree of sub-divisions which have been created. The mass production of highly complicated products (e.g., an automobile) probably presents the thorniest problem of coordination.

Attempts to achieve coordination may take various forms. The most obvious lies in the design of the organisation itself, ‘in which each of the manifold sub-tasks is precisely defined both in content and in time, the entire schedule constituting a programme centrally administered and universally understood’.

In practical situations, where the organisation is required to function under unstable conditions, recourse must be had to the voluntary efforts of individuals to use their initiative to coordinating committees, the encouragement of free interaction among peers and to the extent possible, the close social and geographical positioning of work groups whose activities are particularly interdependent.

A Modern Coordinative Concept:

Instead of defining management in terms of routine functions viz., organising, planning, etc., we can think of it as an integrated activity in which these basic functions are not separated. This way of classifying functions permits us to study those functions analytically.

Modern writers like Herbert Simon, James March, Andreas Papandreou, Richard Cyert and others have suggested that the functions of managers may be classified, for analytical purposes, into two distinct levels of activity: coordination and supervision. The former (coordination) function is that of decision-making — the process of selecting an action from alternative courses of action.

In a sense, the need for this function is universal, since it arises in environment of risk and uncertainty, i.e., in situations where decisions must be made and plans formulated on the basis of expectations. The other phase of management, i.e., supervision, involves the fulfillment of plans already formulated.

It thus requires little, if any, coordination of a decision- making nature. It is management in the coordination sense which is now recognised by many modern contributors to management theory as the central concept.

The justification of the above view lies in the fact that ‘all human behaviour involves, by conscious and unconscious means, the selection of particular actions out of all those that are available to the individual and to those over whom it exercises influence and authority.’

The fundamental role of the coordinating unit — management in its true sense — is that of choosing among alternatives. Choice problems crop up as land, labour, capital and other inputs are scarce relative to their needs and have alternative uses.

The functions of the manager from the coordinative standpoint thus becomes one of making choices or decisions that will provide the optimum means of attaining a desired end, whether the end be the preservation of the existing situation between the organisation and its competitors, or the long-term attainment of domination or any other objective.

But regardless of the goal, managers may classify outcomes as risks or as uncertainties. If knowledge of the future were perfect, decisions could be made and plans formulated and, hence, without the need for subsequent revisions. However, in today’s world of uncertainty, managers are engaged in the continuous process-of charting new courses of action into hazy horizons.

In short, an organisation (as distinguished from a mere physical producing plant), or management (in the supervisory sense), exists largely as a device for dealing with and adjusting to risk and uncertainty. Says H. M. Spencer- “If the future were completely known, management in the coordination sense would be needed for the most part only at the start or initial phase of an investment in order to formulate a plan for the future; thereafter, management in the supervisory sense would be all that is needed for the purpose of administering or carrying out the plan. Apparently, since risk and uncertainty constitute the environment in which businesses operate, planning, organising, controlling, directing, etc. are actually inseparable activities of coordinate management”.

Co-orditional functions of the chief executive:

A final word about the co-ordinational function of the chief executive. It is the man (or woman) at the head of an operation who must set the people working in a vacuum quickly get but of touch.

‘Keeping people in the picture’ is more than a question of communication: it is also the ability to arrange matters in such a fashion that overlapping functions are avoided and, equally important, that no management task is carried out in isolation.

As we shall see later, industrial (business) management has to be concerned with three broad factors: production, marketing and finance. This is a trinity of interests. That each should have its due and that there should be the strictest attention to ensuring that these basic functions are coordinated is the chief executive’s priority. He will achieve his end in different ways.

In some business enterprises, management by committee has been successful. In others, some other coordinating machinery, less cumbersome and time-consuming than the committee method, works better. This may consist of clear statements of policy and action, by the chief executive and the top management team, distributed widely.

The aim, in whatever way it is secured, must be to avoid purposeless (or duplication of) effort since A is unaware of what B is doing.

Coordination of effort, above all, needs to be thought out. A move to set up a new factory or office, or the launching of a product can only be speedy and effective if — in advance of the operation — everybody’s part in it is phased in, clearly started and understood in advance.

To quote R. Falk- ”Management can undoubtedly derive much from a calm appreciation of possibly not more than four basic points which, if constantly borne in mind, can help towards the creation of the sort of conditions in which effective management can function. These are- firstly, the objectives must be clearly stated; secondly, responsibilities must be defined and accepted; thirdly, communications must be defined and accepted; thirdly, communications must be two-way or even three-way and fourthly, the chief executives in any enterprise, of whatever size, must always control and progress the operation, accepting that there are many well-tested techniques (of which intelligent use of information from a computer is one) to enable controls to be sensibly planned”.

Categories of Managerial Activity:

In a broad sense, a manager’s activity falls into three categories:

(a) Design activities:

Firstly, the manager is a designer but as a manager, he designs inter-relationships among systems and resources. A major portion of a manager’s time is spent setting objectives and designing plans, programmes, systems and procedures.

(b) Implementation activities:

Secondly, the manager has to set into motion activities to implement the plans he has designed (or has worked to design as part of a team) : he purchases raw materials, hires people, orders services, etc.

(c) Control/audit/adaptation activities:

Finally, the manager is a controller, auditor and adapter. As Arthur Elkins has put it- “when things do not go according to plan, he (the manager) seeks to learn why the deviation exists, determines whether the objectives were attainable and then either changes the plan or orders appropriate changes in resources or personnel so that objectives are reached and plans fulfilled”.

In short we can divide the activities of a manager into three general functional categories: design, implementation and control/audit/adaptation.

Two points may be noted in this context:

(1) First, managerial activity in the real world is not a series of discrete steps that can be neatly categorised; rather it is a continuous cycle for each action or programme undertaken.

(2) Secondly, the real world manager can hardly afford the luxury of being able to line up problems, handling (tackling) one problem at a time from initial ideas to adaptation and auditing. Rather, a manager is always confronted with a multitude of issues, each in various stages of the cycle; on some he is at the designer stage, on others an implementor and yet others a controller/auditor/adapter.

Management as a Group:

Most people use the term ‘management’ to designate a group of managers instead of limiting the use of the term to describe the specific purposes of planning, organising, leading and controlling. However, there is the need to clarify who is normally considered a member of management.

Managers are persons in an organisation who accomplish their work primarily by directing the work of others. So the pertinent question here: who are the persons performing all or any of these functions of planning, organising, leading and controlling?

In a representative organisation there are a broad of directors, a president, a group of vice-presidents or major executives, managers of divisions or departments and supervisors of specific areas or functions who perform specific duties assigned by the supervisor and report to a departmental supervisor. It is generally agreed that those who direct the work of others are a part of management.

However, there are some people who do not direct the work of others, but still participate in planning, organising, or controlling. These people are usually referred as staff specialists — rather than managers — and are also considered as part of management.

Allocation of the Manager’s Time:

Managers spend their times in different ways in different organisations. In general, “the distribution of a manager’s time spent in planning, organising, leading or controlling is a function of the level of that person’s position in the organisation”. The top-level executives of a company usually spend the major portion of their time in planning and organising.

They are responsible for policy-making which itself is a form of planning. They must also determine the nature and type of organisation necessary to execute these policies. On the contrary, a departmental supervisor directs the operative personnel in one department and is responsible for the amount and quality of work produced.

This explains why a major portion of the supervisor’s time is spent in leading and controlling the efforts of subordinates.

Management Principles:

Management scientists and writers on organisations have developed certain management principles which may be regarded as general statements of organisational and management behaviour. These principles are usually stated in a form that identifies cause and effect relationships.

In other words, principles provide guides to thought and action. “In doing so”, as Trewatha and Newport argue, “they contribute to the avoidance of mistakes by providing insights into possible results”. Consequently, advocates of management principles feel that their application will bring about good results; that is “a more effective and efficient achievement of organisational goals”.

Management is at best an inexact science. This implies that managerial functions are based on certain fundamental principles.

A principle is a fundamental truth and is generally stated in the form of cause and effect relationship. In the words of Koontz and O’Donnell: “principles are fundamental truths which are believed to be truths at a given time, expressing relationship between two or more sets of variables”.

The so-called principles of management are guidelines on organisation structure developed by management theorists like F. W. Taylor, H. Fayol, L. F. Urwick and J. D. Mooney.

The following are the most widely recognised management principles:

(a) span of control — there is an optimum number of subordinates an executive can control;

(b) levels of management — too many levels of management reduce the effectiveness of communication and control;

(c) unity of command — each man should report only to one manager or superior;

(d) delegation — there is need to delegate work to subordinates who should be given sufficient authority so that they can discharge their responsibility properly. But authority should not be relinquished in the sense that the executive who delegates a task himself remains accountable for its achievement;

(e) rational assignment — people should be assigned tasks rationally and economically so as to ensure full utilisation of an enterprise’s human resources (or manpower);

(f) action decisions — matters requiring a decision should be dealt with as near to the point of action as possible; and

(g) line and staff—it is desirable to separate the control of operation as a management function from the provision of services or advice to operational units.

Henri Fayol has emphasised the point that management principles are universal. These can be applied in all types of organisations like business firms, government departments, charitable trusts, hospitals, etc. However, in recent years some commentators, especially behavioural scientists who have emerged, question the universal validity of these principles.

They suggest “paying too much attention to them increases the rigidity of organisations and hence reduces their effectiveness, particularly in rapidly changing conditions”.

Universality of Management:

We have already defined management as a process.

A closer scrutiny reveals that there are three aspects to a such a definition:

1. Firstly, there is the need for co-ordination of resources.

2. Secondly, there is need to give consideration to performance of the managerial functions.

3. Finally, since management is purposeful in nature, it is necessary to include the purpose of the management process.

The manager of an enterprise coordinates the resources of an organisation, especially financial resources, physical resources and personnel to enable the organisation to reach its stated goals or objectives. The co-ordination of resources is achieved through the primary functions of the management process.

In the final analysis management is nothing but “the co-ordination of all resources through the processes of planning, organising, leading and controlling in order to attain stated objectives”.

The above definition of management as a purposive, co-ordinative process is universal in its application to all forms of group behaviour. The term ‘management’ is not restricted (confined) to business enterprises alone. It is applicable whenever people attempt to reach a stated goal through group efforts.

Secondly, the concept of universality of management is also applicable to all levels of managers within an organisation who participates in the coordination of resources and the exercise of one or all of the managerial functions. “All work to achieve the stated objectives”.

Since management lies at the heart of all human activity it is universally applicable. It is applicable to business organisations, hospitals, universities, churches or governmental agencies, as well as in our personal lives.

As Trewatha and Newport argue- “In fact, before any organisation can achieve its goals effectively and efficiently, management is required to co-ordinate the physical factors of money, materials, information, marketing, machines and people. Thus it is referred to as a process in which individuals utilise human and material resources in seeking to accomplish predetermined objectives”.

The concept of universality implies that management and activities are transferable from one organisation to another. This mainly happens in the case of military people who often join industry after retirement. There are of course, instances where such transfers have not been successful.

Thirdly, there is need for flexibility. Managers must have sufficient flexibility when they adjust to new organisational environment. Each organisation has a different environment and for a manager, to be effective in moving from one organisation to another, he or she must be capable of adapting to change.

In this context one may venture-to quote Carl Heyel who writes- “like the domain of ancient philosophers, ‘all mankind’ is management’s province. Management art and science must be brought to bear whenever effort must be organised on a significant scale in government, the cultural arts, sports, the military, medicine, education, scientific research and religion as well as in the profit-pursuits of manufacture and commerce”.

8. Notes on the Challenges of Management:

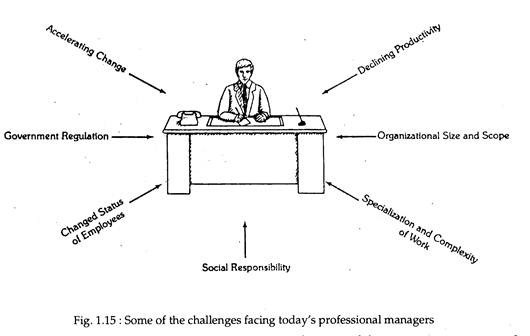

The manager’s job is full of challenges. However, in recent years the opportunities and problems that management faces have grown in completely. (See Fig. 1.15).

The following factors have contributed to this increase in the challenge to management:

1. Organisational Size and Geographic Scope:

As the size of the organisation expands and as business firms go international in search of raw materials and markets for finished goods the task of managing such complex organisation also grows in difficulty.

2. Specialization of Labour and Complexity of labour:

The modern system of production is based on Adam Smith’s concept of specialization and division of labour. Smith cited the example of a pin-manufacturing factory. Eighteen different processes are involved in the production of a simple item like pin. In Bata’s shoe factory there are hundreds of different processes. Managers must integrate and schedule the work of various departments. This is no doubt a complex task.

3. Changed Status of Employees:

In the 1950s, the right of the owner-manager to hire and fire was both recognised and exercised. But today’s employees are more conscious of their rights as members of the organisation. They have more education, stronger desires for individual identity and recognition and less patience for seemingly meaningless work.

They are often represented by unions having strong bargaining power. This transformation calls for greater finesse on the part of contemporary managers.

4. Government Regulation:

In recent years various regulatory agencies like the MRTP Commission, Bureau of Costs and Industrial Prices, Environment Protection Agency, etc. regulate almost all major aspects of organisational policy and behaviour. Consequently contemporary managers must be actually aware of the legal environment in which planning and decision making take place.

5. Accelerating Change:

Finally, managers must also cope with rapid inflation, energy crisis, growing commission, changing social and cultural trends as well as with scientific and technological innovation (See Fig. 1.15).

As Longnecker and Pringle have put it:

“The acceleration in the rate of innovation has altered the requirements for managerial success. Modern management is ineffective to the extent that it is unable to recognise and deal with innovation”.

A manager can hardly afford to emphasize tradition, accept the status quo and rely upon ‘experience’.

9. Notes on the Theories of Management:

No study of management is complete unless one analyses the problem of management theory and” is able to show the relationship between the theories of management and the practice of management.

As Mc Farland has put it:

“The purpose of scientific theory is to provide a framework for the explanation and interpretation of the facts, so that phenomena can be explained, understood, predicted and controlled. Concepts are developed to organise theory and help managers apply their own ideas, facts, business know-how and the ‘conventional wisdom’ of the management can lead to improved decision making and action”.

It is interesting to note that at present there is hardly any unified, comprehensive theory of management. Rather there is ‘an accumulating body of theory of management’.

Some writers on management focus on organisation theory, some on administrative theory and still others on human relations or group-theory. Management scientists (or writers on operations research) treat decision theory as the critical element in explaining management behaviour and action.

On the contrary, people like P. F. Drucker, P. R. Hampton and others prefer to emphasize the manager’s tasks and functions. Consequently diverse theoretical approach with varying hypotheses, assumptions and propositions has evolved. Harold Koontz has described this proliferation of parallel theories as ‘the management theory jungle’.

He found that researchers and writers, mostly from the academic world, were attempting to explain the nature and knowledge of managing from six different points of view, often referred to as ‘schools’.

These were:

(1) the management process school,

(2) the empirical school,

(3) the human behaviour school,

(4) the social system school,

(5) the decision theory school, and

(6) the mathematics school.

The varying schools or approaches have led to a jungle of confusing thought, theory and advice to practising managers.

The major sources of entanglement in the jungle were often due to varying meanings given to common words like ‘organisation’, to differences in defining management as a body of knowledge, to widespread casting aside of the findings of early practising managers as being ‘armchair’ rather than the product of distilled experience and thought of perceptive men and women, to misunderstanding the nature and role of principles and theory and to an inability or unwillingness on the part of many ‘experts’ to understand each other.

Billet feels that the jungle has been made more impenetrable by the infiltration in various colleges and management institutes of many highly, but narrowly, trained teachers who are bright but inexperienced. They are intelligent people but know too little about the actual task of managing and the realities practising managers face.

However, some modern management theories have suggested that variations in theoretical approaches are not very much in conflict. Moreover, integrative forces are almost always at work to bring about a synthesis.

Management theorists have still a long way to go in their effort to reduce the confusion in management theory by developing an integrated theory of management. Management theory emerged slowly prior to the turn of the century, but it has developed more rapidly since then.

McFarland has identified three stages in the evolution of management thought since the early 1900s:

(1) Scientific Management,

(2) The human relations movement, and

(3) Management science and related systems approaches.

Contemporary Management Theory:

At present there are two major theories of management which are discussed below:

1. Systems Theory (Approach):

Among the theories in Koontz’s management theory jungle there is one — systems theory — that can be apply integrated with the current practice of management. A system is defined as ‘anything that consists of parts connected together’. A system is an organised or complex whole: an assemblage or combination of things or parts forming a complex or unitary whole.

To be more specific, a system is composed of parts of a whole related to each other in different ways under varying conditions.

True enough, “systems theory is a powerful concept for the analysis of organisations and organisation behaviour as well as for the design of organisation from the standpoint of technology or engineering or from a behavioural point of view”.

Modern managers are generally realizing that organisations are systems and they are learning how to run the organisation as a system. This is what distinguishes the present views of management from those of the past. In the past managers were well aware of the fact that there was interdependence among the various parts of an organisation and its environment.

For example, early scientific management thinkers like F. W. Taylor and others, who were basically engineers by profession, saw in the development of machines the possibilities of the automatic factory, in effect, a production system integrating the flow of inputs, processing and the flow outputs as a whole.

However, they often lacked a full appreciation that an organisation is a system. They thought that “the most effective way to operate the system was to find the best way to perform a task and put it into effect”. But modern managers have learnt from experience that “the organisational system works most effectively when there are various ways of performing tasks, each one evaluated as best for a different situation”.

In truth, the total organisation is an important part of systems analysis. As David R. Hampton argued: “In an organisation, people, tasks and management are interdependent just as the nerves, digestion and circulation are interdependent in the human body. A change in one part affects the others, inescapably. Like an organiser, an organisation is a system”.

At present various aspects of organisation are proving amenable to systems analysis such as the marketing and distribution systems, engineering and scientific functions, financial activities among people in an organisation. In fact, almost all types of organisation can employ systems thinking.

Open V. Closed Systems: