This article throws light upon the two main steps for constructing persuasive sales manager. The steps are: 1. The Basis of Persuasive Sales Messages – Identifying Objectives 2. The Basis of Persuasive Sales Messages Organizing the Message.

Step # 1. The Basis of Persuasive Sales Messages – Identifying Objectives:

There are two important steps in constructing persuasive sales messages (and all persuasive messages for that matter). The first is identifying the objectives of the letter; the second is organizing the message.

To identify the objectives of a persuasive message, you must answer three questions:

a. What product or service is being promoted? (the subject)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

b. To whom is the message being directed? (the audience)

c. What are the desired results? (the purpose)

These questions require knowledge of the product or service, the customer, and the desired action.

Know the Product or Service:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The better you understand the product or service to be sold, the more effective you will be in writing a persuasive message. For example, to promote a low cost life insurance policy, you might – if you were aware of the low-price – begin a sales letter in the following way:

“You can insure your family’s security for only two rupees a day”.

To persuade someone to buy your product or service, you cannot be satisfied with knowing the product in a general way. You need details. Before you write, you need concrete answers to such questions as:

a. What will the product do for the people concerned?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

b. From what materials is it made?

c. By what process is it manufactured?

d. What are its superior design features?

e. What is its price?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

f. What kind of servicing, if any, will it require?

Similar questions must be answered about competing products. Of particular importance is the question, “what is the major difference?” People are inclined to choose an item that has some advantage not available in a similar item at the same price.

Know the Customer:

A persuasive letter must appeal to the reader. This means you must know something about the individual to whom the letter is directed. For example, in the case of those people receiving the letter announcing a low-cost insurance policy, you need to know their age range, their general need for insurance, and how much coverage they are likely to require.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The targeted group should be people who currently have little insurance and can profit from an inexpensive supplement to their current coverage.

When writing to a group of customers, try to answer these questions:

a. Who would buy this product?

b. Why would they buy it?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

c. How frequently would the product be purchased?

d. How would the product be used?

e. Is this product a necessity or a luxury?

f. What do people like about it?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

g. What do people dislike about it?

You can ask yourself many similar questions to examine and uncover the needs of the readers and their attitude toward the product. To this end, demographic data and psychographic profiles of readers provide useful information.

Know the Desired Action:

What do you want your reader to do? Fill out an order form and enclose a personal cheque? Return a card requesting a representative to call? Whatever the desired action, you need to have a clear definition of it before beginning to compose the letter.

Step # 2. The Basis of Persuasive Sales Messages Organizing the Message:

An inductive or indirect approach is effective for sales letters and other persuasive messages.

The selling procedure includes four steps:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

a. Getting the readers’ Attention. (A)

b. Introducing the product and arousing Interest in it. (I)

c. Generating Desire for the product through convincing evidence. (D)

d. Encouraging Action. (A)

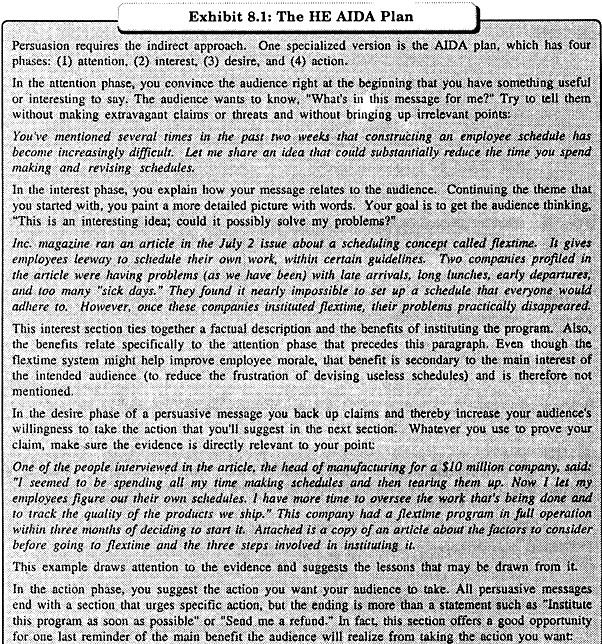

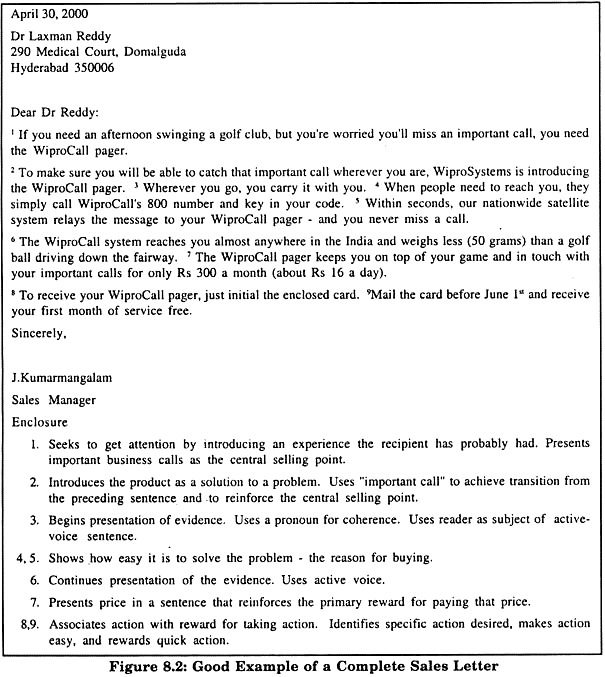

These steps – popularly known as AIDA – Constitute the basic outline for sales letters (See Exhibit 8.1). Each step is essential, but the steps do not necessarily require equal amount of space. Good sales writing does not require that we have separate sentences and paragraphs for each phase of the letter. Points (a) and (b) could appear in the same sentence; point (c) could require many paragraphs.

The four-point outline is appropriate for unsolicited sales letters. Solicited sales letters have been invited by the prospect; unsolicited letters have not. Someone who has invited a sales message (by requesting information) has given some attention to the product already; as a result the attention- getting sentence is hardly necessary.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Such a sentence is essential, however, when the recipient is not known to have previously expressed interest. The very first sentence is then deliberately designed to get the reader’s attention. To understand the organization and composition of a persuasive sales letter, let us examine four- broad divisions of the message: using the attention-getter, introducing the product, convincing the reader, motivating action.

First Paragraph: An Attention-Getter:

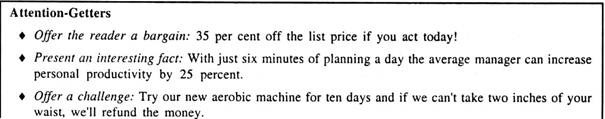

Various attention-getting techniques have been successful in convincing recipients to put aside whatever they are doing and considering an unsolicited letter.

Some commonly used methods are illustrated below:

a. A Solution to a Problem:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Writing-analysis software that identifies your mistakes helps you create error-free, professional documents.

b. A Startling Announcement:

More teens die as a result of suicide each month than in auto accidents.

c. A What-if Opening:

What if the boss announced, “we’re going to increase efficiency in our department by 30 percent?”

d. An Outstanding Feature of the Product:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

An answering machine that lets you check messages in the office when you are hundreds of miles away on business!

e. A Gift:

Ten free sheets of embossed, personalized stationery are enclosed as a free sample. You can experiment with many such action-oriented, attention-getting openings. See Figure 8.1 for more suggestions on such opening statements. Unfortunately, many action-oriented statements lose the reader’s interest. Here are some guidelines that can prevent this.

i. Avoid cliches: Boring, oft repeated statements should be avoided. Try not to use introductions like, “A penny saved is a penny earned,” “A stitch in time saves nine,” “Time and tide wait for no man.”

ii. Avoid asking foolish questions: “Are you interested in improving your health?” will always be answered with a “yes”. So why ask it? Instead, focus on selling points: “We can help you get in shape in just three hours a week.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Regardless of the attention-getting technique we choose for any persuasive message, we should ask ourselves some pertinent questions:

(a) Is the attention-getter related to the product and its virtues?

(b) Does the first sentence introduce a central selling feature?

(c) Is the attention-getter addressed to the reader’s needs?

(d) Does the attention-getter sound interesting?

(e) Is the attention-getter original?

(f) Is the first paragraph short?

Start with the product:

The beginning sentence of the first paragraph must suggest a relationship between the recipient and the product. And the sentences that follow the first sentence should grow naturally from it. If readers do not see the relationship between the first sentences and the sales appeal, they may react negatively to the whole message – they may think they have been tricked into reading.

The main problem lies in getting the reader’s attention in an appropriate way. Is the following attention-getter related to the product and its virtues?

Would you like to make a million?

We wish we knew how, but we do know how to make you feel like a million. Have you tried our latest mentholated shaving cream?

The beginning sentence is short and, being a question, emphatic. But it suggests that the remainder of the letter will be about how to make a million, which it is not. All three sentences combined suggest that the writer is using high-pressure techniques. The mentholated cream does have virtues; one of them could have been emphasized by placing it in the first sentence.

Focus on a central selling feature:

Almost every product will in some respects be superior to the competing products. If it is not, such factors as favorable price, fast delivery, or superior service may be used as the primary appeal. This primary appeal (central selling point) must be emphasized, and one of the most effective ways to emphasize a point is by position.

An outstanding feature mentioned in the middle of a letter may go unnoticed, but it will stand out if mentioned in the first sentence.

Note how the following sentence introduces the central selling feature and leads naturally into the sentences that follow:

A complete collection of Hussain prints – only at Poster Shop.

You can select complete sets of prints by Bendre and Aziz, as well as Hussain, at the Poster Shop, the only fine arts poster dealer with this comprehensive selection of works of art by the “masters.” Poster Shop will also frame these prints professionally so you can display them in your home as proudly as you would the originals.

Address the reader’s needs:

Few people will buy just because doing so will solve a problem for someone else. How would a student react to the following sales opening?

After years of effort and expense, we have developed an electronic dictionary.

With the emphasis on the seller and the seller’s problems, the sentence isn’t particularly appealing. Revised, the beginning paragraph is changed to focus on a problem the reader has:

Your first draft is complete. Time is short and your spelling must be perfect. You can use Right- Spell (an electronic dictionary) to meet your term-paper deadline.

This “you” attitude – empathizing with the audience’s needs – is an important factor in all communication; and it is particularly important in persuasive communication. Before and during writing, think in terms of reader interests.

Keep paragraphs short:

The spaces between paragraphs provide convenient resting places for the eyes. What is your psychological reaction to a fifteen-line paragraph? Doesn’t reading it seem an arduous chore? A reader is encouraged to take the first step if it is a short one. If possible, hold the first paragraph to three or fewer lines.

A one-line paragraph (even a very short line) is acceptable. You can even use paragraphs less than one sentence long! Put four or five words in the first line and then, after a series of dots, complete the sentence in a new paragraph. Be careful to include key attention-getting words that either introduces the product on lead to its introduction.

Introducing the Product:

A persuasive message is off to a good start if the first sentences cause the reader to think, “Here’s a solution to one of my problems,” “Here’s something I need,” or “Here’s something I want”. We may lead the recipient of the message to such a thought in the first sentence.

If we do, we’ve succeeded in both getting attention and arousing interest in one sentence.

If the introduction of the product is to be effective, we need affirmative answers to the following questions:

(a) Is the introduction natural?

(b) Is the introduction action-oriented?

(c) Does the introduction stress a central selling point?

Be natural and cohesive:

If the attention-getter does not introduce the product, it should lead naturally to that introduction. One sentence should grow naturally from another.

Note the abrupt change in thought in the following example:

Strained eyes affect human relationships. The Lakeview Association of Office Managers has been conducting a survey for the last five months. Their primary aim is to improve lighting conditions.

“Strained eyes,” the first words of the first sentence, are related to “lighting conditions,” the last words of the last sentence. But the thoughts are too far apart. Moreover, no word or phrase in the first sentence is readily identified with the words in the second sentence. The abrupt change in thought is also confusing.

See how the relationship between the two sentences has been improved in the following example:

Strained eyes affect human relationships. That’s one thing the Lakeview Association of Office Managers learned from their five month survey of office lighting conditions. For light that is easy on the eyes, they’re switching to Philips Easy Glow. When you flip on your Easy Glow lights, you get….

The second sentence is tied to the first by the word “that’s.” The light of the third sentence refers to the “lighting” of the second sentence. And the Easy Glow light is introduced as a solution to the problem of strained eyes. It is not enough just to have ideas that are related to each other; these ideas must be closely woven together in such a way that one sentence leads smoothly to another.

Be action oriented:

To introduce a product in an interesting way, we should be action oriented (that includes using the active voice). Action is eye catching – it holds attention and interest more readily than description. Place the product in your reader’s hands and talk about their using it.

The reader will get a clearer picture by reading about something “happening” instead of a tedious product description. And the picture is all the more vivid when the recipient is the hero of the story – the person taking the action.

A small amount of product description is necessary and natural, but too many sales writers overdo it, as in the following excerpt from a sales letter promoting a projector: This VM601 Kamcord is housed in a die-cast aluminum case. It has a 750-watt bulb, pitch- control knob, and easy-to-use, swing-out film gate.

See how each sentence has a thing as the subject. We’re looking at a “still” picture. Now let’s turn on the action. We’ll make a person the subject and watch that person do something with our projector.

Lift this Kamcord. See how easy it is? That’s because of the lightweight aluminum case. Now swing the film gate open and insert the film. All you have to do is keep the film in front of the groove embossed on the frame. See how easily you can turn the pitch-control knob for the range of sound that suits you best. And notice the clear, sharp pictures you get because of the powerful 750-watt projection bulb

In a sense, we don’t sell products – we sell what they will do. We sell the pleasure people derive from the use of a product. Logically, then, we have to write more about that use than we do about the product.

Stress the central selling point:

If the attention-getter doesn’t introduce a distinctive feature, it should lead to it. We can stress important points by position and by space. As soon as readers visualize our product, their attention has to be drawn to its outstanding features. These features are emphasized by being mentioned first.

Moreover, if we want to devote much space to the outstanding features, we have to introduce them early. In the following example, note how the attention-getter introduces the distinctive selling feature (ease of operation) and how the subsequent sentences keep the reader’s attention focused on that feature: Your child can see vivid moving pictures of this year’s birthday party – and from a machine so easy to use that your child can operate it.

Watch your child lift the Kamcord combination video recorder. See how easy? We kept the weight down to 2kg by using an all-aluminum case. Let your youngster set it on a coffee table, chair, or kitchen table – easily.

Now, swing the film gate open and insert your film. All you have to do is keep the film in front of the groove embossed on the frame. See how easily you can turn the pitch-control knob for the range of sound you like best. And notice the clear sharp pictures you get because of the powerful 750 watt bulb.

By stressing one point, you do not limit the message to that point. For example, while ease of operation is being stressed, other features – pitch control, swing-out film gate, and 750-watt bulb – are mentioned. A good sales letter should stress a central selling point; but this does not mean that other points have to be excluded.

Convince the Readers with Evidence:

After introducing the product in an interesting way, we have to present enough supporting evidence to convince our readers to purchase the product (or take suitable action). We should keep one or two main features of the product uppermost in the reader’s minds, and the evidence we present should support those features.

It would be inconsistent, for example, to use appearance as an outstanding selling feature of compact cars while providing abundant evidence to show economy of operation.

Use concrete language:

Merely saying that a children’s book is durable will not convince people. We must present information that shows what makes it durable; we must also define how durable.

In the “convincing-evidence” portion of the sales letter, we need all the information we have gathered about the product.

We can establish durability, for example, by presenting information about the manufacturing process, the quality of the raw materials, or the skill of the workers:

TCC Publishing’s Arora Classics will last your child a lifetime – pages bound in durable gold – embossed hardback, treated with special protectants to retard paper aging, and machine-sewn (not glued) for long-lasting quality. The 100-percent cotton fiber paper can withstand years of turning the pages. The joy of reading can last for years as your children explore the world of classic literature with TCC’s Arora classics.

The evidence presented must not only be authentic, it must also sound authentic. In certain cases, the use of facts and figures can be powerful. Facts can be very impressive and increase reader confidence. However, do not go overboard and inundate your readers with an abundance of facts or technical data that will bore, frustrate, or alienate them.

Never make your readers feel ignorant by trying to impress them with facts and figures they may not understand.

Be objective. Use language that people will believe. Specific, concrete language makes letters sound authentic. Unsupported superlatives, exaggerations, flowery statements, unsupported claims and incomplete comparisons make letters sound like high-pressure sales talk. Examine the following statements to see whether they give convincing evidence. Would they make a reader want to buy?

These are the best plastic pipes on the market today. They represent the very latest in chemical research. How do we know these pipes are the best? We don’t know, and the writer can’t convince us by simply using superlatives. The writer should have researched plastic pipes, identified the qualities that made them superior, and then illustrated those features in the pipes referred to in the sales letter.

Take a look at the following statement:

Gardeners are turning cartwheels in their excitement over our new weed killer!

Doesn’t that statement sound preposterous? And if we don’t believe in the cartwheels, can we believe in the weed killer?

Use interesting attention-getters, describe the product in a lively manner, but be objective at all times. Go overboard with the descriptions, and your reader might just trash your sales letter.

Interpret the evidence:

Since your readers will be less familiar with the product and its uses than you will be, you will have to interpret the evidence for them where necessary. In other words, indicate how the information will benefit the readers.

For example, note the limitations in the following description:

This calculator weighs 14 grams. Its dimensions are 7 ½ by 5 ½ by 1/10 centimeters. It comes in black or ivory.

In what way is a 14 gram unit superior to a 200 gram one? Or is a 200 gram unit actually better? Is there any advantage in having a calculator of these dimensions? What would be the disadvantage if it were twice as big?

Now see how interpretation makes the letter more convincing:

Compare the weight of this calculator with the weight of a credit card. The credit card may be heavier than the calculator’s 14 grams. See how easily it fits inside a wallet. That’s because its dimensions are 7 ½ by 5 ¼ by 1/10 centimeters – about the size of a playing card.

The revision shows what the figures mean in terms of reader benefits. It also makes use of a valuable interpretive technique – the comparison. We can often make a point more convincing by comparing something unfamiliar with something familiar. Most people are familiar with the size of a playing card, so they can now visualize the size of a calculator.

Be careful when you talk about price:

Once readers start learning about the benefits, they wonder “How much is this going to cost?” If this question is not handled properly, the sale will be lost.

Here are a few guidelines for handling the price discussion:

a. Introduce price only after presenting the product and its virtues.

b. Keep price talk out of the first and last paragraphs – unless price is the distinctive feature. The price should be mentioned at the beginning of a paragraph only if it is the most important selling point.

c. Use figures to illustrate how enough money can be saved by the product to pay for the expenditure.

d. State price in terms of small units. (Twelve rupees a month seems a lot less than Rs. 144 a year.)

e. If practical, invite comparison with similar products.

f. If facts and figures are available, use them to illustrate that the price is reasonable.

g. Mention price in a complex or compound sentence that refers to the virtues of the product. In this way, the sentence that mentions the price also reminds readers of the benefits they get in return.

h. The price should appear in some position other than the first or last word of a sentence. First and last words are emphatic; but unless it is the central selling point, price should be subordinated.

When talking about the price, bear in mind that the objective is to present the product or service as affordable.

Last Paragraph: Motivating the Reader to Action:

Our chances of getting action are increased if we:

(a) State the specific action wanted;

(b) Refer to the reward for taking action in the same sentence in which action is encouraged;

(c) Present the action as being easy to take;

(d) Provide some stimulus for quick action; and

(e) Ask confidently for action.

Mention the specific action you want:

Unless specific instructions are included, such general instructions as “let us hear from you,” “take action on the matter” are ineffective. Whether the reader is to fill out an order card and return it with a cheque, place a telephone call, or return an enclosed card, define the desired action in specific terms.

Refer to the reward for taking action:

For both psychological and logical reasons, readers are encouraged to act if they are reminded of the reward for acting. So the distinctive selling feature of the product should also be worked into the parting words.

Present action as being easy to take:

Instead of asking readers to fill in their names and addresses on order forms or return cards and envelopes, do that work for them. If action is easy or consumes little time, they may act immediately. Otherwise, they may procrastinate.

Provide a stimulus for quick action:

The longer the reader waits to take action on our proposal, the dimmer our persuasive evidence will become. Reference to the central selling point helps to stimulate action. Here are some commonly used appeals for getting action.

Buy while present prices are still in effect.

Buy while the present supply lasts.

Buy before Diwali.

Buy now while a rebate is being offered.

Ask confidently for action:

Avoid statements like “if you agree…” and “I hope you will”. Such expressions indicate doubt on the part of the writer. Instead of saying “if you want to save time in cleaning, fill in and return..,” say confidently, “to save time in cleaning, fill in and return….”

For good appearance and proper emphasis, the last paragraph should be kept relatively short. Yet the last paragraph has a lot to do: it must indicate the specific action wanted, refer to the distinctive selling feature, present action as being easy to take, encourage quick action, and ask for it confidently.