Everything you need to know about:-Measuring Advertising Effectiveness.

List of some of the most suitable methods used for Measuring Advertising Effectiveness and Advertising Campaign

Measuring Advertising Effectiveness (With Methods)

The evaluation of advertising is divided into media research, copy research and sales results research. The multivariable forces influencing sales make it almost impossible to measure with high precision the sales effect of advertising.

Consequently, most advertising research measures the characteristics of an advertisement, such as exposure, and the ability of the receiver to comprehend, retain and believe in the advertisement. If all of these are present, it is inferred that the advertisement will be effective in producing sales.

The problem of measuring advertising effectiveness is still a frontier area for the application of complex scientific methods to market cultivation effort, particularly in Indian conditions, in which advertising industry is growing; and its problems are closely tied to the economics and cultural problems of the country.

Worth of Advertising:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

How much is advertisement worth? This is the question that is being asked all over the world, and certainly by the management in India. In the face of mounting advertising costs, on the one hand, and a squeeze on profitability, on the other, top managements are increasingly concerned about the cost benefit of advertising in the operation of a business.

This concern is understandable, for advertising is one of the few, if not only, item of expenditure in a company’s balance sheet that cannot be measured in terms of its specific contribution toward its sales or profitability.

When a sales manager wants to enlarge his staff, or a works manager wishes to buy machinery, he can project with reasonable certainty the additional sales or production that would result and correlate the extra expenditure with the resulting revenue. An advertising manager, ideally, should also be able to do this; but, in most cases, he cannot.

This apparent lack of accountability of advertising is increasingly becoming untenable today. Hard pressed with the escalating cost of raw materials, salaries and wages, strangulated by higher overheads and taxes, the managements of companies are finding it extremely difficult to approve any expenditure that is not likely to bring in additional profit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Advertising, therefore, has to prove its contribution to the total marketing effort like any other allocation of corporate resources; or else advertising expenditure will run the risk of being set arbitrarily or even slashed drastically.

The techniques of advertising measurement have admittedly not fully developed, and are yet a highly controversial matter; few experts are agreed on how advertising actually works or how its effectiveness may be precisely measured.

But, surely, in spite of the conflicting theories, it is possible to introduce a greater sense of realism in the setting of advertising objectives and goals, so that its evaluation is not subject to the caprice of individual opinion.

The principle of management by objectives provides a useful starting point. In any investment planning, there is a statement of investment objectives which are spelt out in detail, together with a statement of the nature and size of the returns expected on the investment. Advertising is a marketing investment; its objectives can therefore be put down in a similar manner, clearly indicating the results expected from the campaign.

What is Advertising?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The value of advertising cannot be determined unless its role and function are understood; the “unaccountability” of advertising, in most cases, arises from a lack of appreciation of what advertising can or cannot do.

Advertising should be viewed as a part of the total marketing effort of a company. The glib answer to the question- “Why do companies advertise?” is- “To sell product.” But, in recent times, an increasing number of advertising practitioners have been frankly admitting that advertising cannot actually sell products.

Supporting this view, the Association of National Advertisers, USA, defined advertising as a “mass, paid communication, the ultimate purpose of which is to impart information, develop attitudes and induce action beneficial to the advertiser” (which may lead to the sale of a product or service).

Advertising, the Association emphasized, was only one in a series of tools in the “marketing-communications mix”; the other tools are person-to-person selling, retailer recommendation, publicity, special promotions, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Ostensibly, the job of advertising is to perform certain communications jobs with greater speed, volume and economy than can be done by any other means. This pragmatic approach to advertising is fundamental, and must be accepted before any plans for measurement can be formulated.

Objectives and Goals:

Next, it is necessary to define advertising objectives and goals. To measure results, it is even more necessary to distinguish between advertising objectives and advertising goals. An objective is a broad aim; a goal is a specific and quantified task. The one is not measurable, the other is.

Often, advertising objectives in marketing plans are vaguely worded in general terms, such as “to increase sales profits,” “to expand our share of market,” or “to maintain a favourable attitude towards our company among the trade and consuming public.” Evaluation is not possible in these cases simply because there are no definite criteria for evaluation.

The examples cited relate to total marketing objectives, not advertising tasks. Marketing objectives may be stated’ in terms of sales or market shares; advertising objectives only in terms of communication. Advertising gives added value to brands by appealing to the consumer’s reasoning, senses and emotions; but, it cannot effect direct sales.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The ideal advertising goal not only makes its point in terms which may be used as a yardstick for performance evaluation but can also be stated as “a specific communication task to be accomplished among a defined audience to a given degree in a given period of time.”

Example of quantifiable advertising goals would be to “ensure that the advertising message, that brand ‘X’ gives more shaves than any other because it has………………… properties is made known to 10 million people of the target audience”; or “to increase awareness by ten per cent among the target group of the following – the brand name and the knowledge that the cleaning action of this brand is greater than that of any other washing powder because it contains more powerful bleaches,” or “to communicate to all existing purchasers of the brand that it has improved because the product is now sealed in a new airtight container to maintain freshness and aroma.”

Process:

To arrive at such specific goals, it is first necessary to identify the market and the target group in geographical, and, as far as possible, socio-economic terms, and determine the message and the media that will be suitable to persuade the potential buyer.

Then, from the total marketing mix, the particular communication tasks will have to be separated out, to form the advertising objectives. These should be translated into specific goals and stated in quantitative terms, so that the measurement of achievement may be possible.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Second, when the goals have been thrashed out, they should be written down and agreed upon by all the parties who are involved in making decision on advertising or who are responsible for implementing the communication function. This not only helps in the creation of advertising but also cuts down waste, for everyone has the same agreed goals in mind and acts with a common purpose, instead of pulling in different directions.

Once this basic approach is agreed upon, plans should be drawn up to reach the goals. And giving a price tag to each task that is necessary to achieve the goal according to its priority rating, a detailed cost analysis, of the entire operation should then be made and the advertising budget prepared. Then the creative and media plans should be worked out.

The campaign which is then developed should be pre-tested to evaluate whether or not the advertising is likely to communicate the given goals. Bench marks can be set at this stage to establish brand position prior to advertising; and after the campaign has run, a further study may be made to assess the change and, generally, the extent to which the advertising has achieved the goals.

This is a continuous process, the successes and failures of one campaign helping to improve the -next one.

Advertising Copy Research:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Advertising deals with imponderables. Since people differ so greatly in their wants, in the economic and other motives which actuate them, and in the various ways by which their interest is aroused, it happens that some advertising is more effective than others.

Tens of thousands of rupees are thrown away every year in printed matter, so it is said, not only because the advertising does not get to the right people but because it carries an appeal which does not interest those to whom it goes. An often-quoted remark is that half the money spent on advertising is wasted; but no one knows, which half.

The government and business rely heavily on advertising to influence favourably the minds, emotions and actions of the people toward a particular idea or brand. Advertising is expensive, but is vital to the success of the advertiser. The advertiser wants his audience to see his advertisement. He wants them to read it. Above all he wants his advertisement to stimulate desire and to aid in the sale, of an idea or a product.

Advertising copy research seeks to find out how well an advertisement succeeds in attracting attention, and how well it delivers the intended message about a product or an idea. The theory behind such a test is that an advertisement, to be effective in selling a product or an idea, must first attract attention and deliver its message.

It covers tests of the effects of a complete advertisement, or certain elements in the advertisement and of the dominant theme of an advertisement or campaign.

The Purpose of Copy Testing:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The ideal copy research programme has, as its objective, the measurement of an advertisement’s effectiveness before it appears in its final form, during and after its exposure to the audience, to determine whether and to what extent it has accomplished its assigned task.

In this way, advertising may be controlled for the improvement of future advertising.

The test is made before (pre-test and after-post-test) an advertisement has been run. Pre-tests measure the effectiveness of different presentations of the message, including alternative presentations of the single theme. They help one to select the best for of advertisement before incurring the expense and risk of presents it on a full-scale run.

They are intended to discover both the strength and the weaknesses of an advertising campaign and of the individual advertisements.

Post-tests measure the impact of the message. They seek to discover which advertisements and what elements of various advertisements get the best response, what position produces better results, what medium or issue of a medium pulls better, or how well a whole advertising campaign is progressing. They provide information on whether a brand name or the selling theme of a given advertisement or advertising campaign has penetrated the reader’s mind, and the extent of this penetration.

It must be clearly understood that advertisement testing is not designed to help in setting creative strategy or in the development of advertising ideas. Its task is to provide guidance on the relative importance, in terms of consumer interest, of various possible advertising appeals.

Methods to Evaluate Advertising Effectiveness:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Methods of Copy Testing:

All copy testing procedures fall in the major types given below. All theme approaches may be used for the pre-testing of advertisements.

In addition, the methods at (iii), (iv) and (vi) may be used as post-tests.

(i) Consumer-jury survey;

(ii) Coupon-return analysis;

(iii) Recognition test;

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iv) Recall or impact test;

(v) Sales area test;

(vi) Psychological analysis;

(vii) Controlled experiment.

Each test has its limitations but all of them have been demonstrated to be valid measures of relative interest taken by readers in various advertisements.

(i) Consumer- Jury Survey:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This test is designed to learn, from a typical group of prospective customers, their preference for one advertisement over another or for several advertisements out of a group. Advertisements which have not yet been published are mocked up on separate sheets, and these are presented to the consumer-jury either in personal interviews or group interviews.

The juror is instructed to rank the advertisements in terms of his likes and dislikes. His verdict shows the relative action provoking power of the advertisements.

Advertising themes or snatches of copy may also be judged in personal interviews with a consumer-jury. The alternative wordings under consideration are printed on separate cards. These are placed in the hands of the respondent, two at a time. The respondent reads each of these and selects the one he considers most effective in terms of his personal reaction.

Another variation is the gift test in which the respondent is asked to choose one brand from a variety of brands as described in different advertisements. In the projective technique, the respondent is shown a picture of consumer using or buying the brand and is asked to select, from a variety of statements, the most applicable one for describing the situation.

In the product use test, the respondent is given two “types” of a product to use and evaluate. The two “types” are actually the same product, each accompanied by a different copy theme.

The major value of this test is its separation of the stronger from the weaker advertisements, the sheep from the goats.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Coupon-Return Analysis:

Various themes, advertisements or elements are measured on the basis of the number of enquiries received in response to an offer contained in the advertisement.

The devices used are:

(a) An open coupon offer of a standard premium; or

(b) A “hidden offer”; or

(c) The use of the split-run technique.

The open coupon offer is generally a free sample of the product. The giving of the sample is considered a more accurate gauge of the selling power of the advertising copy than an unrelated premium.

In the hidden offer technique, a premium offer is buried in the copy, usually near the end of the advertisement. This device is directed to those persons who are sufficiently attracted by the advertisement to read it completely.

It also eliminates the “coupon bounds” who glance through media for free or inexpensive offers. But one must be cautious in using this method because of the comparatively small number of returns received as a result of hiding the offer in this way.

The split-run technique consists of running different advertisements in separate sections of a magazine or newspaper so that a different advertisement appears in each half or third or fourth of the entire issue.

By means of coupon returns or other means, it is determined which advertisement pulls best. When publications do not permit split-runs, the different advertisements must be run at other times on as nearly a comparable basis as possible.

(iii) Recognition Test:

It determines the readership of advertisements in the publications and is conducted by personal interviews with readers and magazines or newspapers. The interviewers locate the readers of the particular issue of the publication in question. They then go through the publication, page by page, with the respondent indicating those advertising elements which he or she recognises as having read.

The scores developed by the recognition method indicate the proportion of qualified readers of a publication who claim to have “seen” (noted), “read some” or “read most” of the elements of individual advertisements.

The above describes the method used for post-testing. In a pre-test, a portfolio of advertisements is used. The respondent is asked to go through the portfolio, then it is taken away, and the respondent is asked; “What advertisements do you remember seeing?” The recognition test may thus be combined with the recall or impact test which has been described below.

(iv) Recall or Impact Test:

The recognition test measures the stopping power of the advertisement but does not tell us what the reader understood or retained of the advertisement. The recall or impact test is designed to measure the positive impressions of the advertisements. In response to the question asked by the interviewer, the reader reveals the accuracy and depth of his impressions by his answers.

A portfolio containing test advertisements or one test advertisement among several control advertisements is placed in the hands of the respondents who are asked to read the advertisements, taking as much or as little time as they want. All interviewing is done immediately after the respondent has finished reading the advertisements.

The performance of one advertisement is evaluated against all others. The respondent is asked a series of unaided or aided recall questions to determine which advertisements are remembered and which features stand out.

Another approach is to place a dummy magazine with a family and then call back a week later to pick up the magazine and interview readers on their recall of advertisements in the magazine.

(v) Sales Area Test:

This measures the effectiveness of an advertisement by determining the resulting amount of sales. Trial campaigns employing different themes or copy presentation techniques are run in a group of local markets, and sales are then measured by store audits.

This test, however, is not employed extensively because of the difficulty of controlling the many variables likely to distort the results, such as differences between markets, competitive activities, sales efforts, seasonal demand, and media.

(vi) Psychological Analysis:

The whole process of advertising is psychological in character. It is natural, therefore, that certain psychological procedures should be adapted for copy testing.

Four psychological testing techniques are most commonly used:

(a) Tests of readability and comprehension;

(b) Tests of believability

(c) Attitude tests; and

(d) Triple associates tests (theme penetration). The interviews are carried out in depth among a small target group of people.

(a) Tests of Readability and Comprehension:

These are made by means of a series of penetrating questions and by other techniques devised by psychologists to determine, in advance of publication, the ease of readability and comprehension of the proposed copy.

(b) Tests of Believability:

An advertising message must have a high degree of credibility for readers. Measurements of credibility may employ a scale technique, in which various statements or product claims are rated by consumers. Another method is to ask respondents which parts of an advertisement they find hard to believe after they have been exposed to it.

(c) Attitude Tests:

Various types of attitude tests have been developed by psychologists and applied to copy testing. Typical consumers are exposed to sample advertising messages, either printed or oral. The attitudes produced by these various messages are then determined by means of a series of penetrating questions.

Psychological reactions, such as age, involvement, the type of person who would use the product, and the personality of the product reflected by the advertisement that is tested, are obtained. The researcher looks especially for elements in the advertising which arouse psychological hostility.

(d) Triple Associates Tests:

This ties in advertising with recall by seeking to learn the extent of the consumers’ association with the product, brand name and copy theme. The test is useful only when the advertising features a specific theme or slogan, which the reader may remember. This procedure is sometimes known as “theme penetration.”

(vii) Controlled Experiments:

They are similar to the sales area test in general character but are conducted on a much smaller scale. One method is to make use of display material or signboards at the point of sale. Different advertisements may be placed in different groups of stores, and the effectiveness of each may be measured by the resulting sales.

A variation of this method is to attempt to sell the product from door to door. The percentage of successful sales is the basis for measuring the value of each theme. Yet another method is to distribute to consumers handbills with coupons, offering a cash discount. Each handbill represents a different advertisement for the product. The coupon redemption will indicate the sales effectiveness of the different advertisements.

In selecting the respondents for these tests, care should be taken to see to it that they bear on the target audience and that various types among them are adequately covered. Unless the sample is properly controlled, the results may be quite erroneous.

Advertising Goals:

If a firm’s advertising goals are to be achieved and ad effectiveness increased, the manager must attempt evaluation. To do so he requires better methods of learning how advertising affects the buyer’s behaviour. But this is a very difficult undertaking because measurements are imperfect and imprecise.

The effectiveness of advertising is measured by the extent to which it attains the objectives set for it. In this sense, advertising is like any other form of business activity.

In a very real sense, the integrity of promotional activities rests on how well those activities work. An advertising budget that is spent to accomplish some poorly defined task is more likely to be viewed as an economic waste than a similar expenditure for which the results can be precisely measured.

Any social institution upon which a significant portion of our total productive’ efforts is expended should be able to point to its specific accomplishments. Indeed, it is a source of discomfort both to those with paranoiac inclinations in the business of promotion and to outside critics that the specific results of advertising activities have not always been subject to precise measurement.

There are those, both practitioners and critics, who feel that promotion will only be accepted as a socio-economic institution with “full” rights and privileges “when the means exist to prove that; advertising rupees are productive rupees”. It is undoubtedly a source of no little embarrassment that although we have launched successfully Insat-IB, India’s multipurpose satellite into orbit which beamed back TV pictures, we are unable to say in definitive terms what a Rs. 10,000 expenditure on advertising will accomplish.

The exact result of a given advertising expenditure is extremely difficult to predict because:

(a) The reaction of consumer-buyers to the advertising effort cannot be known in advance;

(b) The reactions of competitors cannot be accurately anticipated, and

(c) Fortuitous events that may influence the results of the advertising efforts cannot always be predicted.

Consider the hypothetical case of a retailer who contracts to spend Rs. 500 with a local newspaper for a special sales event. The ad is run, and the crowds are greater than their early estimates. What caused the success of the sale? The advertisement? The low prices that were quoted during the sale? Was it because the products themselves were superior?

Or did it have something to do with the fact that, on the day of the sale, there were no competing sales of a comparable nature anywhere in the city? Or, indeed, did it have something to do with the beautiful weather that prevailed during the sale? Alas, the success of the sale was doubtless due to all these things, and the exact role of any one of the elements is virtually impossible to isolate.

The problem is one familiar to all social scientists, namely, the inability to establish in advance the precise cause-and-effect relationships when a multitude of variables impinge upon a particular event.

It is entirely possible that even with poor advertising support, a sale may prove to be a success because everything else falls into its proper place. It is likewise possible that an effective advertising effort may be limited in its performance by offsetting factors that work counter to it. Critics of mass advertising techniques would clearly have less to criticize if it were possible to predict accurately the results of a given advertising expenditure; but the complexity to the environment in which the promotional expenditure is usually incurred largely precludes accurate forecasting.

But to concede that it is virtually impossible to predict the effects of an advertising effort is not to say that we cannot measure the effects of particular advertising effort.

One of the activities with which advertising executives are concerned is the assessment of the effectiveness of the advertising effort. The management needs answers to such questions as- “Was the advertising campaign really successful in attaining our objectives?” “Were our TV commercials as good as those of competitors?” “Will the magazine advertisements, which we have designed, make consumers aware of our new products?”

Tests of effectiveness are needed to determine whether proposed advertisements should be used, and if they will be, how they might be improved, and whether ongoing campaigns should be stopped, continued or changed.

In accomplishing these purposes, marketers use pre-tests and post-tests. They conduct pre-tests before exposing target consumers to the advertisements, and post-tests after consumers have been exposed to them.

Advertisers are interested in knowing what they are getting for their advertising rupees. That is why they test the proposed advertisements with a pre-test and measure the actual results with a post-test.

In the past, pre-testing of advertising messages was handled mainly by advertising agencies. But advertisers have been taking an increasingly active role in the pre-testing process. There may be pre-test both before an advertisement has been designed and executed, after it is ready for public distribution, or at both points.

During pre-testing, there is often research on three vital questions:

(i) Do consumers feel that the advertisement communicates something desirable about the product?

(ii) Does the message have an exclusive appeal that differentiates the product from that of the competitors?

(iii) Is the advertisement believable?

Although advertisers spend money on pre-testing, they also post- test their promotional campaigns.

There are at least three distinct reasons for measuring advertising results.

These Are:

(i) The need to produce more effective advertising;

(ii) The need to prove to the management that a higher budget will benefit the firm;

(iii) The need to determine the level of expenditure that is most promising.

Most research focuses on the communication effect rather than on the sales effect. The short-term effect of advertising on sales is, no doubt, slight and unimportant, whereas, in the long run, its effect on brands and companies may be of great importance. For this reason, advertisers ate particularly concerned with their impact on consumer awareness and attitudes.

The main goals of most advertising are to capture the attention of a potential buyer and promote brand awareness.

Awareness builds a favourable for at least a curious attitude toward the product, which leads to experimentation “I will try it once and see how it is.” If the trial is satisfactory, the consumer may stick with the product.

There are many critical and unresolved issues in determining how to test the communication effects of advertising.

These are:

(a) Exposure Conditions– Should advertising be tested under realistic conditions (an actual on-the-air commercial) or under more controlled laboratory conditions?

(b) Execution– It is often expensive and time-consuming to pre-test a finished advertisement. Does pre-testing a preliminary execution produce accurate and useful data?

(c) Quality vs. Quantity Data– Quantitative data are easiest and most precise measurement. But qualitative data from in-depth interviews may provide information that short answer questions never can (a strong negative attitude exists regarding the use of humour in life insurance advertisements).

Many types of advertising tests are used. In TV, commercials testing, a sample of people are invited to a studio to view a programme, with commercials included. The audience is then surveyed about the commercials.

Print advertisements are tested through “dummy” magazine tests and portfolio tests. In the former, a magazine with test advertising in it is sent to a sample of readers, who are later surveyed. In the latter, about 10 to 12 advertisements are placed in a booklet that is shown to respondents; one of these is the test advertisement. The readers are asked to examine and comment on all advertisements in the booklet.

It is much more difficult to assess the sales effect of advertising than the communications effect. Nevertheless, many firms try to measure the effectiveness of advertising in terms of its sales results.

The practice is almost always misleading, although there are some exceptions. For example, direct-mail advertising for magazine subscriptions can require (for example, Span) that coupons be returned by interested customers.

In this situation, the management may count the number of coupons returned. If the objective is to achieve a specific number of coupon returns, the effectiveness of the campaign can be measured. Similarly, of a TV commercial, the sale results may be measured if the commercial message says something like- “Call 25691 to purchase.”

In most advertising situations, it is far more difficult, if not impossible, to establish the exact relationship between advertising activity and sales.

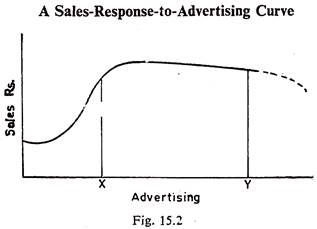

The curve in Fig. 15.2 suggests that some sales will occur even though there is no advertising. Up to Rs. X in spending, advertising appears to have a little impact, probably because it is not yet adequate enough to cross the threshold and enter the consumer’s awareness.

Beyond Rs. Y, there is little or no increase in sales (perhaps even a decline), because the market is saturated, or because some consumers are irritated by increased exposure.

Advertising does not occur in a vacuum. It is only one of the variables that affect the sales results. There are many other variables, both in the marketing process and in other aspects of business operations.

It seems clear that, with few exceptions, the circumstances under which all other variables can be kept constant, so that the precise effect of advertising on sales can be measured, are almost non-existent.

Added to this is the fact that an advertising campaign is itself made up of a variety of factors, such as media, messages, colours, page or time-of-day locations, the size of the headline, and the appeals used. Thus, even if the advertising variable is isolated, this would still not answer questions about the effectiveness of the individual components of the advertising campaign.

Sales Effectiveness Measurement:

For those advertising managers who firmly believe that advertising must be evaluated by determining its impact on sales, some measures of sales response to advertising must be devised. Because of the many influences on sales in addition to that of advertising, the total sales of a product from the period in which the advertising was run are not a valid measure of advertising effectiveness.

The only exception is in those rare cases where the management believes that advertising is the sole, at least the most important influence, on sales. However, where advertising objectives are stated in terms of sales, it is desirable to measure the effect of the advertising campaign on sales.

(a) Historical Sales:

Some insights into the effectiveness of past advertising may be obtained by measuring the relationship between advertising and product (or brand or company) sales over several time periods. For example, a multiple regression analysis of advertising expenditures and sales would show how sales changes have corresponded to changes in advertising expenditures.

This technique estimates the contribution advertising has made to “explaining,” in a correlational rather than a causal sense, the variations in sales over the time periods covered in the study.

The data required for this approach are period advertising expenditure, which may be obtained from company budgeting records, and product sales measured by such techniques as store audits, warehouse shipments, or other sales records maintained by a company.

Of course, a historical sales analysis is only a post-test measure of advertising effectiveness, and is not applicable to pretesting.

(b) Experimental Control:

To establish more clearly a causal relationship between advertising and sales, it is essential to have experimental control, which is considered to be quite expensive when related to other advertising effectiveness measures; yet it is possible to isolate advertising contribution to sales.

Moreover, this can be done as a pre-test to aid advertising in choosing between alternative creative designs, media schedules, expenditure levels, or some combination of these advertising decision areas.

One experimental approach to measuring the sales effectiveness of advertising is test marketing:

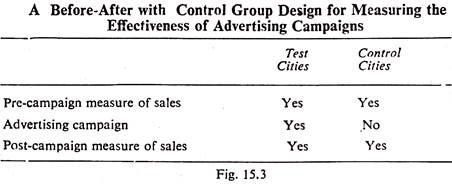

(i) Before-After with Control Group Design:

This classic design uses several test and control cities (Fig. 15.3). The normal level of sales is calculated for both types of cities prior to the campaign, and then the campaign is presented to the test cities and not the control cities. The level of sales is then calculated for both the control and test cities.

The effect of the advertising campaign is calculated by subtracting the amount from the differences between post- and pre-campaign sales in test cities.

The difference between the post and pre-campaign sales in test cities is a function of advertising plus all the other factors. The post pre-campaign differences in sales in the control cities is a function of all the other factors.

By subtracting the sales differences in control cities from those in test cities, a tolerably accurate estimate of the effect of advertising is obtained, provided that the test and control cities are reasonably comparable.

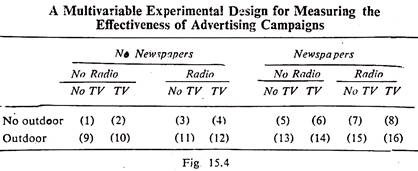

(ii) Multivariable Experimental Designs:

While the experimental design above yields a reasonably accurate estimate of the effect of the advertising campaign on sales, it does not generate explanations for the success or failure of the campaign. Multivariate designs produce these explanations, and are therefore used by some very large advertisers because of their superior diagnostic value. Fig. 15.4 presents a classic multivariate design.

The power of this factorial design is explained by G. H. Brown, former Fords Director of Marketing Research. For any single medium, eight geographic areas have been exposed, and eight have not been exposed. Thus, it is possible to observe how each medium behaves alone and in all possible combinations with other media.

If identical dollar expenditures (at national rates) are established for each medium, area 1 will receive no advertising expenditures; areas 2, 3, 5. And 9 will receive advertising at the same dollar rates; areas 4, 6, 7, 10, 11. And 13 will receive advertising at twice this dollar rate; areas 8, 12, 14, and 15 at three times the dollar rate; and area 16 at four times this dollar expenditure.

This type of factorial design is capable of measuring the effectiveness of all combinations of media used, as well as four different levels of advertising expenditures. For these reasons, it is a very efficient design. However, the complexity and cost involved make it impractical for all but very large advertisers.

Indirect Measures:

Because the measurement of the direct effect of advertising on broad company goals, such as increased profits or sales, is so difficult, most firms rely heavily on indirect measures. These measures involve such factors as customer awareness or attitudes, or customer recall of advertising messages or portions thereof.

The assumption is that a favourable or improved awareness, attitude and/or recall will lead in some way to the attainment of greater sales and profits, or whatever is the primary object of the marketing and corporate strategy.

This assumption, in turn, rests on assumptions about human behaviour that are by no means firmly established or universally accepted. It seems obvious that making a housewife aware of a brand will not necessarily bring about a purchase. Moreover, even if she does buy the brand, it may not be due to the advertisement. It may, in fact, have nothing to do with the advertisement.

Despite the uncertainties about the relationship between the intermediate effects of advertising and the ultimate results, there appears to be hardly any alternative to the use of indirect measures.

Among the types of measures commonly used are:

(i) Exposure to Advertisement:

In case of print media, for example, estimates are made of the readership of individual advertisements by interviewing members of the audience of the magazine or newspapers in which the advertisement has appeared.

In order to be effective, advertisements must gain exposure. The management is concerned about the number of target consumers who see or hear the organization’s messages. Without exposure, advertising is doomed to failure.

Marketers may obtain an idea of the exposure generated by a medium by examining its circulation or audience data, which reveal the number of print copies sold, the number of persons passing the billboards or riding in transit facilities, the number of persons living in a tele-viewing or radio-listening area, and the number of persons tuned into various TV and radio stations at various points of time.

The media cross-classify circulation and audience data by such variables as the age, occupation, income, and areas of residence of the audience or reader population. As a result of the examination of such data, advertisers can determine the approximate number of target consumers that are exposed to advertising messages.

Another means of gauging exposure is through readership or listener surveys. Here, interviewers ask consumers if they have read, viewed or listened to advertisements. Readership tests provide a useful supplement to the circulation data, since the circulation data do not indicate how many target consumers actually read the advertisements.

(ii) Attention or Recall of Advertising Message Content:

A widely used measure of advertising results is the recall of the message content among a specified group or groups of prospective customers. Recall is usually measured within 24 hours.

Advertisements cannot be effective unless they attain the attention of target consumers. One means of testing the attention- getting ability of one or more advertisements is to ask consumers to indicate the extent to which they recognize or recall each one.

Researchers may conduct such inquiries in a laboratory setting. Here, consumers read, near or listen to the advertisement, and then evaluate it in a per-test. Another method is to ask consumers for indications of recognition or recall after the advertisement has been run (a post- test). These measures assume that consumers have attended to that which they can recognize or recall.

Various mechanical devices in the Western world provide indices of attention. The eye camera, for instance, measures the paths taken by the eyes as a subject views an advertisement. This device indicates which parts of the advertisement he or she reads and how much time is devoted to each part.

Another method is to measure the size of the subject’s pupils when exposed to advertising. The puplis tend to dilate when something pleasant or interesting is perceived, constrict when something unpleasant or uninteresting is seen or heard, and remain unchanged when the response is neutral.

Thus, a change in size is indicative of attention. An analysis of inquiries for messages presented in advertisements provides a measure of attention.

(iii) Product or Brand Awareness:

The marketers who rely heavily on advertising often appraise its effectiveness by measuring the customer’s awareness of a product or brand. This type of measure is subject to much of the same criticism as is applicable to sales measures, that is, the awareness is affected by many factors other than advertising. But, for new products, changes in awareness can often be attributed to the influence of advertising.

(iv) Comprehension:

Consumers utilize advertisements as a means of obtaining information. They cannot be informed, however, unless they comprehend the message. Various tests of comprehension are available.

Marketers use recall tests as indicators of comprehension. The implication is that consumers recall what they comprehend. Another measure of this variable is to ask subjects how much they comprehend a message they have recently heard or viewed. One may employ a somewhat imprecise test of the comprehension of a newspaper and radio advertisement.

One may, from time to time, ask individuals he considers to be typical target consumers such questions as- “What did you think of my new commercial ?” and, “Did it get the message across ?” The answers to such questions provide valuable insights into advertising decision making.

(v) Attitude Change:

Since advertising is usually intended to influence the state of the mind of the audience toward a product, service, or organization, the results are frequently measured in terms of expressed attitudes among groups exposed to advertising communication.

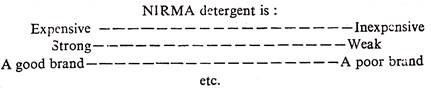

Various types of attitude measures are used, ranging from questions about willingness to buy or the likelihood of buying, to the measurement of the extent to which specific attributes (for example, “modern”) are associated with a product.

An assessment of attitude change calls for the measurement of attitudes toward the product or organization in question, both before and after the appearance of the advertisement.

The researcher may conduct this in a laboratory setting (a pretest) or in conjunction with the appearance of the actual advertising effort (a post-test).

Attitude scales are useful means of gauging attitudes.

A typical scale contains questions such as:

The measuring instrument normally contains 15 to 20 scales, such as the three set forth above. Scaling techniques of this sort (called the semantic differentials) provide a useful means of measuring attitudes in a short period of time.

Other ways of gauging attitudes are analyses of recall and inquiries. The assumption underlying these methods is that consumers remember or inquire about matters toward which they hold favourable attitudes. In addition, some researchers utilize the pupil dilation test in evaluating this variable.

(vi) Action:

Finally, an important advertising objective is to stimulate action or behaviour. The intention-to-buy measuring instruments can provide measures of proposed actions.

These instruments include such points as the following regarding the product under consideration:

(a) I already own it.

(b) I hope to buy it within the next year or sooner.

(c) I will probably buy it sometime in the future.

(d) I have no idea whether I shall even buy it.

(e) I am sure I will never buy it.

An analysis of these responses yields measures of consumer buying intentions and are indicative of expected future purchasing activities.

One type of action that advertisers attempt to induce is buying behaviour. The assumption is that if an increase in sales follows a decrease in advertising expenditure, the changes in sales levels are good indicators of the effectiveness of advertising.

Logic suggests that measurements of sales are preferable to other measurements. After all, are not most advertisements used to increase or maintain sales, either directly or indirectly?

Some problems arise in the use of sales tests. Sales, depend upon a number of factors, not only on advertisements factors that may seriously disrupt the test. Sales increases may be the result of a decrease in the rival’s advertising expenditure, an increase in his prices, a decrease in the strength of the organization, a more aggressive personal selling effort by company personnel.

An increase in income, improvements in the weather and many other factors. In short, external factors may easily contaminate the results.

Another problem is the difficulty of measuring the impact of advertising upon sales over a period of time. A housewife may read an advertisement for a new brand of refrigerator and, as a result, be impressed by the product. Yet she may not buy the brand until two years later, when she sees it in a store.

Or, the advertisement of a soft drink producer may stimulate a purchase which makes the consumer loyal to the brand; yet the sales may be spread out over the next ten or twenty years. Most sales tests do not take measurements over so long a period. Even if they did, other factors probably would contaminate the results.

Some advertisers utilize sales tests, despite their limitations. The marketers whose advertisements solicit mail orders, for instance, frequently employ this technique.

Another type of action test consists of tabulating the number of coupons that consumers redeem. The coupons are placed in advertisements and consumers are asked to take them to retail outlets and purchase the brand at a discount. If a large number of consumers redeem their coupons, the advertiser assumes that the message was powerful in generating action.

The purpose of some advertising is to generate inquiries. Thus, a good measure of effectiveness is to tabulate their number. Similarly, retailers may count the number of consumers who visit their outlets, both before and after the appearance of the advertisements in question.

Finally, lottery tests provide measures of action. The researcher presents a sample of consumers with a list of brands and asks- “Which of these do’ you want to receive if you turn out to be the winner of our lottery?” Then the researcher exposes the subjects to one or more advertising messages.

Following the exposure, the researcher again asks the subjects which brand they would prefer if they win the lottery. Those advertisements featuring brands that are mentioned by more consumers in the “after” than in the ‘before” measurement are deemed to be more effective in attaining their objective.

Measuring Advertising Effectiveness

The intelligence with which planning is conducted can be greatly enhanced if the planner can measure the results of what has already been done. This is as true of advertising as it is of any other activity. The essence of measuring advertising effectiveness is to determine what influence, if any, the advertisement has had on the thinking and actions of the people who make or influence buying decisions. Unfortunately, no generally applicable technique for achieving this purpose with assured accuracy has yet been developed.

There would appear to be rather general agreement, though, that attempts to measure advertising effectiveness must be individual to the firm and must begin with a clear understanding of the purposes each advertisement or program is designed to achieve. Methods may then be developed to determine the extent to which each purpose has been accomplished.

For example, if a program was designed to stimulate demand, the flow of orders before and after its initiation could be determined, along with the cost of selling the additional volume. Admittedly, this approach has a few holes in it, the worst being that frequently the influence of advertising cannot be separated from that of other activities going on concurrently.

However, if no other activity was in progress to which a given increase in sales could be attributed, the advertising program would appear to be its principal cause.

If the purpose of advertising is to identify new customers, the extent to which it does so can be measured at least in part by the number and kind of inquiries it generated. An inquiry usually contains internal evidence of the stimulus which triggered it.

If inquiries obtained by advertising are followed up and result in sales, the cost of the inquiry and the subsequent cost of making the sales can be computed. This makes possible the calculation of an advertising cost per dollar of sales associated with the advertising.

If an advertising program was intended to create an image or dispel a prejudice, an attitude survey conducted before and after the initiation of the program may reveal the extent to which its purpose has been accomplished. Whether or not the purpose, or the extent of its achievement, is worth the cost is much more difficult to determine.

However, management must have decided that the purpose was worth at least the amount budgeted for it. Consequently, the cost of complete or partial achievement can be computed and compared with the expenditure originally approved.

Measuring the effect of advertising designed to disseminate information can be done by thorough before-and-after surveys of what sample members of the target audience know about the subject matter presented. The cost and value considerations are the same as those which apply to an image or attitude objective.

While this discussion barely scratches the surface of the subject, its intent is merely to indicate that it is possible to devise methods with which the results of much industrial advertising can be measured with an acceptable degree of accuracy. The cost of measuring performance may, of course, exceed the value of the information it provides. In such cases, one can reasonably question whether or not advertising itself is worth its cost.

Measuring Advertising Effectiveness (Evaluation, Issues & Guidelines)

Advertising planning and development is a complex process which requires multitude of decisions. Different people participate directly or indirectly at each stage of the ad development process and hold stake in performance of the ad. Advertiser, as a spender, holds the prime stake and seeks desired effects of advertising on the target audience.

Advertising agencies are concerned for its image as a developer of creative ads. Media houses and other facilitating organizations also like to be a part of the success stories of the brand as they largely depend on advertising revenues. Though immediate customers/audiences and society at large are not the direct participants in decision making process, their concerns for ad performance are of equal importance.

Customers hold stake for having access to information at the right time and of right type and it has no misleading element in it. Society, at large, is concerned for the allocation of its scarce resources and the effects of advertising on the wellbeing of the society.

Where both the advertiser and the agency hold their stakes. The focus here will be on various aspects of evaluating advertising performance and determining its effectiveness in terms of advertising purpose.

Evaluating Ad Effectiveness:

Advertising effectiveness refer to the changes that advertising causes in the mental or physical state or activities of the recipient of an ad. The continuous process of advertising requires a time-to-time measurement of advertising performance, more accurately called as advertising effects, and its comparison with the standard.

Ad effectiveness is determined by the extent to which advertising performance meets the standard. Here, advertising objectives constitute the standard or criteria for evaluating ad effectiveness. The market environment, the competition level, nature of the product and service, the selling methods being used, the performance of channel of distribution and other situational conditions could interfere with the advertising performance in a given period of time. For evaluating ad effectiveness, these factors are, therefore, kept constant.

Advertising outcomes are slow, and occur over a long period of time, and it is possible that the factors otherwise kept constant at the time of advertising exposure might change in between and influence advertising performance. Hence, there is always a probability of exactly determining advertising effectiveness. At times there are controversies about the effects of advertising and they make the people skeptical raising doubts like, does advertising really work?

Issues in Evaluation of Advertising Effectiveness:

There are issues which need concern at the time of evaluating ad performance and determining its effectiveness. One of them concerns with the parameters of advertising performance which could either relate to change in sales or some communication variable commonly referred to as sales effects or communication effects.

It depends upon advertising objective in a given situation that what would be the parameter of advertising performance and how it is to be measured. However, there is always a possibility of some disagreement particularly due to the fact that advertising objectives differ at different points of time, or differ for different target groups.

Also, the testing techniques to measure performance parameters are many in number and the choice of one best technique at times becomes difficult.

Advertising agencies are significant participants in advertising process and have their own reservations for the system of ad evaluation. Agencies usually hold the opinion that applying measures to evaluate ad performance may interfere with their creativity whereas the norm is that the more creative the ad, more likely it is to be successful.

Also, due to the ambiguousness of testing procedures and of advertising itself, there is always the possibility of lack of true measurement of creativity and effectiveness. Therefore, agencies want to be creative without any limiting guidelines from the advertiser.

Advertisers, being the major stakeholder in running an advertising programme on the hand, are always in the favour of evaluating ad effectiveness so much so that agency’s remuneration is at times being linked to the ad performance itself. So, there is a scope for conflict between the agency and the advertiser.

Lagged effects of advertising, and possibility of disagreements relating to advertising performance brings certain ambiguities that circumvent the evaluation task. There is always the need to justify the time and money spent for this purpose. Where time is the critical factor in terms of availing the new opportunities, money can be spent elsewhere to earn better returns on capital.

But due to the lack of a proper evaluation exercise, the poor advertising programme is a cause of more harm and is likely to have more damaging effects for product performance in the market. In view of huge investments involved there is always a need to avoid the situations of over spending which results into waste expenditure.

The under spending situation is of equally more concern as advertising will fail to achieve its purpose for the lack of sufficient funds. Thus, within the given budget allocations the evaluation of an ad performance enables the advertisers to find out the sufficiency level of expenditure to achieve the advertising purpose.

The various aspects of evaluating ad effectiveness to bring more clarity in this regard. There are four W’s related to evaluation of ad effectiveness and subsequent discussions will provide required explanations to each one of them-

1. What to measure?

2. When to measure?

3. Where to measure?

4. Which method to use for measurements?

Summarized View on Measuring of Ad Effectiveness:

A summarized view on various aspects of decisions concerning evaluation of ad effectiveness are given below.

The following points can be noted in this regard:

1. Measuring ad effects whether for print or broadcast ad, as each form has its own requirements for measurement techniques to be used.

2. Measuring whether there are sales effects or communication effects. Sales effects can adequately be measured only in few of the situations; measurement of communication effects is complex.

3. Advertising objectives provide the measurement criteria.

4. Measurement of ad effects takes place either before and/or after the launch of an ad.

5. Pre-tests occur in pre-launch period at number of point during development of the ad.

6. Pre-tests are of diagnostic nature which involves partial testing of ads for its various elements such as headlines, illustration, concept, layout and so on.

7. There are number of pre-tests, which can be conducted in lab setting or in the field.

8. Post-tests occur in post-launch period and the purpose is to determine the accomplishment of the objectives sought. They serve as input to next situation analysis.

9. Post-tests are the field tests.

10. Data collection methods for various testing techniques can either be based on self- reports or on observation approach.

11. Excepting for few testing techniques, methods for data collection can either be self-report or observation type.

Guidelines for Testing Ad Effectiveness:

There is no best way to test ad effectiveness. Different techniques have been developed to test different advertising variables (input, output or process variables) pertaining to different aspects (media, message, budget) of effectiveness. For example, pre-testing techniques are well suited for measuring message variables but are generally not as appropriate for measuring media scheduling and budgeting variables.

Similarly, different forms of advertising call for different testing techniques. Television and radio ads are required to be measured through techniques different from those used in testing radio ads.

In 1982, twenty one of the largest US ad agencies issued PACT (Positioning Advertising copy Testing) report which viewed advertising as performing on several levels. In order to succeed, an advertisement must have an effect so that it is received (reception), understood (comprehension) and make an impression (response). These are the communication issues which a copy testing should address depending upon the objectives of the specific advertising being tested.

Also, in PACT report agencies agree that it is useful to obtain response to various executional elements such as story elements, illustration, music, characters, etc. which can provide insight about the strengths and weaknesses of the advertising and why it performed as it did. Through PACT report agencies, endorsed a set of principles aimed at ‘improving the research used in preparing and testing ads, providing a better creative product for clients, and controlling the cost of TV commercials.’

This set of nine principles, called PACT (Positioning Advertising Copy-Testing) defines copy testing as research ‘which is undertaken when a decision is to be made about whether advertising should run in the market place. Whether this stage utilizes a single test or a combination of tests, its purpose is to aid in the judgment of specific advertising executions/Copy-testing, therefore, implies that funds will be allocated to research on consumer reactions to the advertising before the final campaign is launched.

The Nine Principles of Good Copy Testing are:

1. A good copy-testing system provides measurements which are relevant to the objectives of the advertising.

2. A good copy-testing system is one which requires agreement about how the results will be used in advance of each specific test.

3. A good copy-testing system provides multiple measures because single measurements are generally inadequate to assess the performance of an advertisement.

4. A good copy-testing system is based on a model of human response to communications—the reception of a stimulus, the comprehension of the stimulus and the response to the stimulus.

5. A good copy-testing system allows for consideration of whether the advertising stimulus should be exposed more than once.

6. A good copy-testing system recognizes that the more finished a piece of copy is, the more soundly it can be evaluated, requiring as a minimum that alternative executions be tested in the same degree of finish.

7. A good copy-testing system provides controls to avoid the biasing effects of the exposure context.

8. A good copy-testing system is one that takes into account basic considerations of the sample definition.

9. A good copy-testing system is one that can demonstrate reliability and validity.

Thus, adherence to PACT principle tends to provide appropriate testing of ad in the pre launch period with the purpose to refine the process of ad development. Yet, the effectiveness of an ad is subject to its performance and its evaluation.

In this Regard the General Criteria are to:

1. Establish communication objectives.

2. Make use of consumer response models.

3. Use multiple measures, and

4. Understand and implement proper research.