Complication of Data and Information for helping you to prepare a presentation on Communication! After reading this article we will learn about:- 1. Communicating among People 2. Importance and Meaning of Communication 3. Process 4. Model 5. Behavioural Processes 6. Networks in Organisations 7. Communication in Groups 8. Managing the Communication Process 9. Organisational Actions and Other Details.

Contents:

- Communicating among People

- Importance and Meaning of Communication

- Process of Communication

- A Model of the Communication Process

- Behavioural Processes that Effect Communication

- Networks in Organisations

- Communication in Groups

- Managing the Communication Process

- Organisational Actions

- Individual Skills Required for Communication

- Informal Communications

- Role of Non-Verbal Communication

- Media and Communication

1. Communicating among People:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Communicating among people is not an easy task as it may appear to a layman. Thus, for managers to be able to communicate effectively, they must understand certain fundamental aspects of the communication process, i.e., how interpersonal factors such as perception, communication channels, nonverbal behaviour, and listening — all work to enhance or detract from communication.

1. Perception and Communication,

2. Communication Channels,

3. Nonverbal Communication, and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. Listening.

1. Perception and Communication:

Perception refers to the process one uses to make sense out of the environment. However, perception in itself often fails to give us an accurate picture of the environment. Perpetual selectivity refers to the process by which various objects and stimuli that vie for our attention are screened and selected by individuals. Certain stimuli fail to catch our attention but others do.

Once individuals recognize a stimulus, they organize or categorise it according to their frame of reference, that is, perceptual organisation. We just need a partial one to enable perceptual organisation to take place. For example, anybody can spot an old friend from a long distance and, without seeing the face or other features, recognize the person from the body movement.

The most common form of perceptual organisation is stereo-typing. A stereotype is “a widely held generalisation about a group of people that assigns attributes to them solely on the basis of one or a few categories, such as age, race, or, occupation.” For instance, young men usually assume that old people have a conservative outlook. Students may stereotype professors of philosophy as absent-minded.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

What is of importance to managers is that they should be aware of the fact that words can mean different things to different people and should not assume that they already know what the other person or the communication is about.

2. Communication Channels:

Managers have a choice of many channels through which to communicate to others (both managers or employees). A manager may discuss a problem face to face, use the telephone, write a memo or letter, or put an item in a newsletter, depending on the nature of the management. In truth, channels differ in their capacity to convey information.

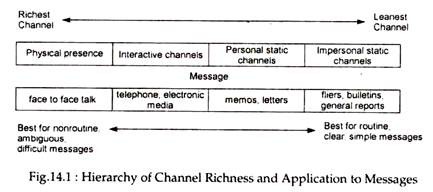

To be more specific, the physical characteristics of a channel limit the type and quantum of information that can be conveyed among managers. The channels available to managers can be classified into a hierarchy based on information richness. Channel richness refers to the quantum of information that can be transmitted during a communication episode. Figure 14.1 illustrates the hierarchy of channel richness.

The capacity of an information channel is influenced by three characteristics:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(1) The ability to handle multiple cues simultaneously;

(2) The ability to facilitate rapid feedback; and

(3) The ability to establish a personal focus for the communication.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On the contrary, interpersonal written media, including fliers, bulletins and computer reports, are the lowest in richness.

Channel selection also depends on whether the message is routine or non-routine. There is no misinterpretation in case of routine messages because they convey data or statistics or simply put into words what managers already agree on and understand. This explains why routine messages can be efficiently communicated through a channel lower in richness.

In a word, routing messages are simple and straightforward. On the contrary, non-routine messages typically are ambiguous, concern novel events, and have great potential for misunderstanding. These are often characterised by time pressure and surprise. It is possible for managers to communicate non-routine messages effectively only by selecting rich channels.

3. Nonverbal Communication:

Such communication refers to messages sent through human actions and behaviours (such as body movements, facial expressions, posture, or dress) rather than through words. It represents a major portion of the messages we send or receive.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Nonverbal communication occurs mostly face to face. So far three sources of communication cues during face-to-face communication have been discovered: the verbal, which are the actual spoken words, the vocal which include the pitch, tone, and timbre of a person’s voice; and facial expressions.

R. L. Dafts has rightly suggested that “managers should pay close attention to non-verbal behaviour when communicating. They must learn to coordinate their verbal and non-verbal messages and at the same time be sensitive to what their peers, subordinates and supervisors are saying nonverbally.”

4. Listening:

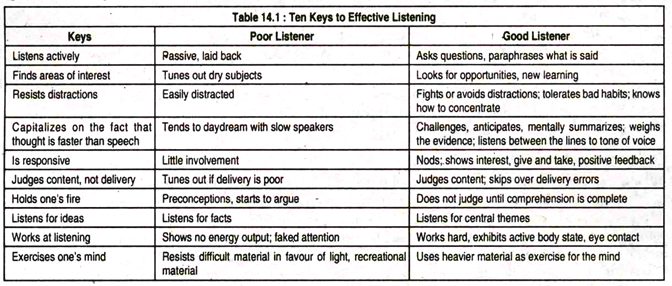

The last important characteristic associated with successful interpersonal communication is listening. A good listener must have certain qualities: he has to find areas of interest, be flexible, work hard at listening and use thought speed to mentally summarise, weigh, and anticipate what the speaker will say. Table 14.1 illustrates a number of ways to distinguish a bad from a good listener.

The listener is responsible for message reception, which is no doubt a vital link in the communication process. The listener must actively seek to grasp facts and feelings and interpret the genuine meaning of the message. Only at this stage can the receiver provide the feedback with which to complete the communication circuit. Listening requires at least 3 things: attention, energy and skill.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Most U.S. multinational firms take listening very seriously. Managers are made to know that they are expected to listen to employees.

2. Importance and Meaning of Communication:

Communication permeates every organisational (managerial) function. It is a problem that plagues many organisations and individual managers. When for instance, managers perform the planning function, they collect information, write letters, memos, and reports, and then meet with other managers to explain the nature of the plan.

When managers act as leaders, they communicate with subordinates with a view to motivating them to accomplish certain tasks. In performing the organising function, managers gather necessary information about the state of the organisation and communicate to others about a new organisational structure.

Thus there is hardly any need to emphasise that communication skills are a basic part of any managerial function (activity). Communication is just a managerial tool designed to accomplish objectives and should not be treated as an end in itself.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In a particular day, the manager performs various tasks — attending meetings, making and receiving telephone calls and correspondence. Ail are a necessary part of a every manager’s job and all clearly involve communication.

The various roles of managers involve a great deal of communication. The three major types of managerial roles of interpersonal, decisions and informational. The interpersonal roles involve interacting with supervisors, subordinates, peers and others outside the organisation.

The decisional roles require that managers seek out information to use in making decisions and then communicate those decisions to others. The informational roles obviously involve communication; they focus specifically on acquiring and transmitting information.

Communication also relates directly to the basic management functions of planning, organising, leading and controlling.

As Griffin has summed up the whole thing in the following words:

“Environmental scanning, integrating, planning time horizons and decision-making, for example, all necessitate communication. Delegation, coordination and organisation change and development also contain communication. Developing reward systems and interacting with subordinates as a part of leading function would be impossible without some form of communication. And, communication is essential to establishing standards, monitoring performance and taking corrective actions as a part of control”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Communication is essentially the process of transmitting information from one person to another and can thus be defined as “the process by which information is exchanged and understood by two or more people, usually with the intent to motivate or influence behaviour.”

3. Process of Communication:

Effective communication is the process of sending message in such a way that the message received is close in meaning to the message, this definition of effective communication incorporates the ideas of meaning and consistency of meaning. Meaning is that which the individual who initiates the communication process wishes to convey.

In effective communication, the meaning is transmitted in such a manner that the receiving person understands it. However it is to be noted at the outset that communication is not just sending information. The distinction between sharing and proclaiming is crucial for managerial success.

A manager who does not listen to others is like a used car dealer who claims, “I sold the car-he just did not buy it.” True enough, management communication is a two-way street that includes listening and other forms of feedback.

Three conditions:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Three conditions are necessary for communication to take place. Firstly, there must be at least two people involved. The relationship between these two people can vary significantly, in terms of proximity, intensity and time. Two managers having a discussion in an office engage in communication. Of course, more than two people may be engaged in consumer. Secondly, there must be information to be communicated. And third, there is need to make so attempt to transmit this information.

In the words of D.K. Berlo, effective communication is as follows:

When two people interact, they put themselves into each other’s shoes, try to perceive the world as the other person perceives it, try to predict how the other will respond. Interaction involves reciprocal role-taking, the mutual employment of empathetic skills. The goal of interaction is ‘the merge of self and other, a complete ability to anticipate, predict and behave in accordance with the joint needs of self and other.

It is the sheer desire to share understanding that motivates executives to visit employees on the shop floor and share food with them. The things managers succeed in learning from direct communication with employees shape their understanding of the corporation.

In a broad sense, communication is the process of transferring meaning in the form of ideas or information from one person to another. It is to be noted that a true interchange of meaning between people includes not only the words used in their conversations. It includes a number of other aspects of human behaviour, viz., shades of meaning and emphasis, facial expressions, vocal inflections, and all the unintended and involuntary gestures that suggest real meaning.

For an effective interchange mere transmission of data is not enough. What is required is that the person sending the message and receiving it rely on certain skills (speaking, writing, listening, reading and the like) to make the exchange of meaning successful.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Communication is the chain of understanding that links the members of different units or divisions of an organisation at various levels and in diverse areas.

It has three major elements:

(1) An act of making oneself understood,

(2) A means of pairing information between people, and

(3) A system for communicating between individuals.

This is the traditional view of communication which may occur between two or among more individuals. This view is being modified by the technological revolution to include communication between people, between people and machines, and even one machine and another (or one machine and other machines).

4. A Model of the Communication Process:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Most organisational people think that communication is a simple task because they communicate without conscious thought or effort. However, a deeper analysis reveals that effective communication is really a complex exercise and in any organisation there are innumerable opportunities for sending or receiving the wrong messages.

Often managers say, “But that’s not what I meant.” There are also occasions when a manager gives people directions in a clear fashion (at least in his own opinion) and they still get lost. Often a subordinate wastes time on misunderstood instructions.

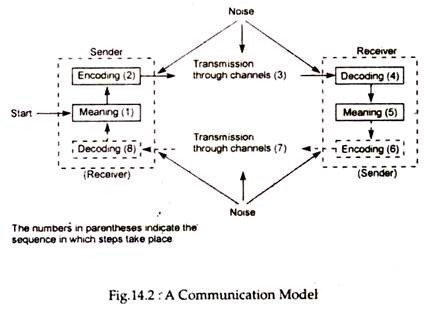

These are some of the situations in which individuals fail to communicate effectively with one another. In order to understand the reasons for such failure, we may now examine a model of inter-personal communication developed by C. Shannon and W. Weaver in 1949. The model is described in Fig. 14.2 below.

One-way communication (or communication from one person to another) involves five steps: meaning, encoding, transmission, decoding, and meaning. In the case of two-way communication (involving interaction between people), the three steps of encoding, transmission, and decoding are repeated as the second person responds to the first.

The process begins when one person (a sender) initiates a communication exchange. This person has decided that a fact, idea, opinion, or similar concept needs to be transmitted to someone else. This fact, idea, or opinion has meaning to the sender, whether it be simple and concrete or complex and abstract. Thus meaning is the first step in the communication process.

The next step is to encode the meaning into a form appropriate to the situation. This encoding might take the form of words, facial expressions, gestures, or even artistic expressions and physical action.

Obviously, the selection of an appropriate form for encoding the meaning is one point in the process where problems can arise.

After the message has been encoded, it is transmitted through the appropriate channel. The channel by which this present encoded message is being transmitted to you is the printed page. Other common channels include face-to-face discussion, the air waves (usually one-way communication) and telephone lines. Transmission is step 3 of the communication process.

Next, the message is received and decoded by one or more other people via such senses as eyesight and hearing. And, after the message is received, it must be translated into meaning relevant to the receiver.

In many cases, this meaning prompts a response, and the cycle is continued when the new message is sent by the same steps back to the original sender (steps 6,7, and 8). As suggested in Figure 14.2, “noise” may disrupt the process after it is transmitted but before it is received. Noise can literally be noise, such as someone coughing, a truck driving by, or two other people talking close at hand.

It can also include such disruptions as a letter being lost in the mail, a telephone line going dead, or one of the participants in a conversation being called away before the communication process is completed.

5. Behavioural Processes that Effect Communication:

Since communication involves more than one person, we would expect emotional and psychological differences between people to affect the communication process. And, the behavioural processes that probably have the most impact on communication are perception and attitudes.

Perception and Communication:

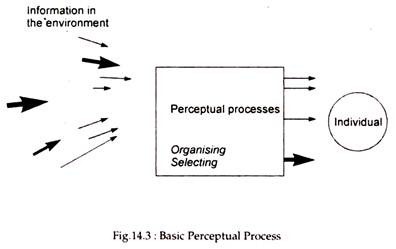

Perception can be defined as “the processes an individual uses to receive information from the environment”. This means that perception exploits the five senses of hearing, seeing, feeling, tasting and smelling. In terms of communication, perception plays a major role in receiving the message transmitted from the sender (step 3 in Fig. 14.2) and decoding it (step 4 in Fig. 14.2).

For managers the barrage of information takes the form of sales forecasts, phone calls and conversations. As Fig. 14.3 shows, perception acts as a filter for organisational people. It screens out information that is trivial and irrelevant. Perception helps us select and organise information from the external environment of business.

Selection:

Selection (also known as selective perception) is the process of screening out information organisation people are uncomfortable with (cost saving by a rival firm) or just do not want to bother about (development of a new sales promotion strategy by a competing firm).

Organising:

As we select and filter information from the external environment, it is to be organised. Organising refers to the process of categorising, grouping and filling in information in a systematic fashion. Information is organised either by stereotyping or by grouping it into categories. After organising information, it is also necessary to fill in gaps to make it more meaningful.

Attitudes and Communication:

A second important behavioural process that can affect communication is the attitudes of the people involved. As attitude is a person’s predisposition to respond in a favourable or unfavourable way to an object (in this sense, an object can be a person or an idea or even a physical object). All people develop their own attitudes toward jobs, other people and everything else they come into contact with.

People’s attitudes have three basic components, viz., emotional, knowledge and behavioural. The emotional component is the individual’s feelings about the object, i.e., it reflects whether a person likes or dislikes the object and how central this like or dislike is to his (her) personal value system.

The knowledge component of an attitude is the beliefs and information the person has about the object. The third output of an attitude is behavioural interrelation. Because of how we feel about the object and what we think we know about it, we develop intentions of how we expect to behave. However, people’s behavioural intentions change with changes in circumstances.

Attitudes are closely related to both the decoding (step 4) and the meaning (step 5) stages of the communication world presented in Fig. 14.2. They also influence the receiver’s responses. Attitudes interact with perception within the communication process. In short, attitudes help determine what information people selectively perceive and how they organise it.

Interpersonal Communication:

Interpersonal communication normally refers to communication between a small number of people. Such communication is of three types – oral, written and nonverbal.

(i) Oral Communication:

Oral communication involves face-to-face conversation, group discussions, telephone calls and other situations in which the sender uses the spoken word to communicate. The main advantages of this form of communication is that it allows prompt feedback in the form of verbal questions or agreement, facial expressions and gestures. Oral communication is easy and can be done with little preparation and without any equipment.

However, oral communication may suffer from problems of inaccuracy as the speaker chooses the wrong words to convey his (her) meaning or leaves out pertinent details, as noise disrupts the process, or as the receiver forgets part of or all of the message. In a two-way discussion, there is hardly any time for a thoughtful, considered response or for introducing many new facts. And, there is no permanent record of what has been said.

(ii) Written Communication:

Written communication may solve most of the problems inherent in oral communication. However, this type of communication does not occur presently. Moreover, it is not respected by managers.

The most serious drawback of written communication is that it slows feedback and often leads to misunderstanding. This problem can easily be solved by a phone call.

On the positive side, written communication is often quite accurate and it provides a permanent record of the communication which, in future, can serve as an ‘evidence’ of exactly what took place.

(iii) Non-Verbal Communication:

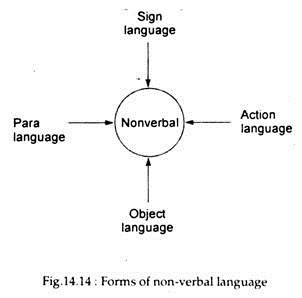

It refers to any communication exchange that does not use words and that uses verbalization to carry more meaning than the strict definition of the words themselves. Facial expressions, body movements, physical contact, sneers and gestures may all be used.

Study has indicated that three important kinds of nonverbal communication are practiced by managers: images, settings and body language. Images in this context refer to the kinds of words people elect to use.

The setting for communication refers to such things as boundaries, familiarity, the home turf and other such elements. Organisational theorists have written much about the symbols of power in organisations. The size and location of one’s office, the kinds of furniture in the office, and the accessibility of the person in the office all communicate useful information.

Body language is the third form of nonverbal communication. The distance we stand from someone as we speak, for example, has meaning. Positioning oneself closer than customary may signal familiarity or aggression. Another effective means of nonverbal communication is eye contact. Depending on the situation, prolonged eye contact might suggest either hostility or romantic interest. Other kinds of body language include body and arm movement, pauses in speech and mode of dress.

Organisational Communication:

Unlike interpersonal communication discussed so far, organisational communication involves broad pattern of communication, involving a large number of people. To start with, we may discuss various organisational communication networks.

Communication Network (channels):

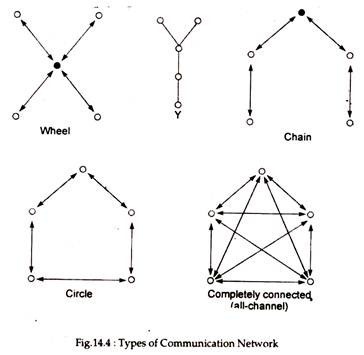

Communication networks refer to certain structured arrangements of a small number of individuals who are allowed to transmit information and communicate with one another only in a set and well-defined pattern. Simply put, a communication network is a pattern through which the members of the group communicate. Four types of networks have been discussed in groups numbering three, four, five members. See Fig.14.4

1. The wheel network:

In this network one member is at the center and four (or more) members are at each end of a spoke. In the wheel, all communication flows through one central person who is probably the group formal or informal leader. Obviously this network is highly centralised because one person receives and transmits all information.

2. The Y network:

The Y is slightly less centralised: two persons are closer to the centre.

3. The chain network:

In this case two members serve as endpoints; each can communicate directly with one person in the middle. The middle members act as relay points to the individual at the centre. The chain begins to offer a more even flow of information among members.

The path is closed by the shaded circle. In such a situation, the central person communicates directly only with the two middle members. They can have any communication with the end individuals. So, the chain network is also centralised. But, it is not as centralised as the wheel network.

4. The circle network:

It is to some extent decentralised in the sense that each individual in it can communicate with the other two next to him.

5. The completely connected (all-channel) network:

It allows a free flow of information among all group members. This type of network is highly decentralised in nature. In this situation, every individual in the group can participate equally and communicate directly with every other individual in the group and the group’s leader, if there is one, is not likely to have excessive power.

Consequences:

(a) Centralised Networks:

It may be noted that the two highly centralised networks — such as the wheel and the chain — are effective in solving routine and clear problems that mainly involve information gathering. This is logical in the sense that the individual at the centre of the wheel and chain networks is processing and weeding out the information the group generates, thus totally ignoring irrelevant communications.

Furthermore, in these types of communication networks, the leadership position of the central individual is strong. It is because he stands the strongest chance of influencing the other members of the group. The final point about centralised networks is that these groups structure their communication patterns very rapidly, since everyone learns quickly that he must process information through the individual in the central position.

(b) Decentralised networks:

Two decentralised networks such as the all-channel and the circle are more appropriate when the group is faced with a non-routine or ambiguous problem. Since, under these two systems, individuals can communicate directly with each other they feel free to express opinions and to generate various solutions; mostly of a creative and innovative nature.

The members of the groups enjoy a greater degree of satisfaction than in centralised networks because they are allowed to communicate with one another and to express their own points of view.

6. Networks in Organisations:

The practising manager can supply these findings to the behaviour of small specialised work groups within an organisation. In case of structured work which is to be performed by the members of the group in a set and routine fashion, the manager is possibly dealing with a centralised network.

On the contrary, if the manager directs the activities of a group whose work is non-routine, he seems to be a part of a decentralized network. Virtually all the properties of formal network models are found to exist in actual work groups most of the time. Unskilled employees, for instance, who perform repetitive jobs on the assembly line, work in centralised networks in the sense that the pace of the assembly line allows only limited communication among individuals.

Formal Communication Flows:

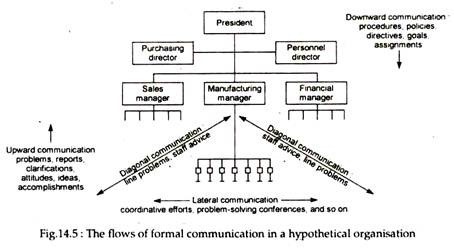

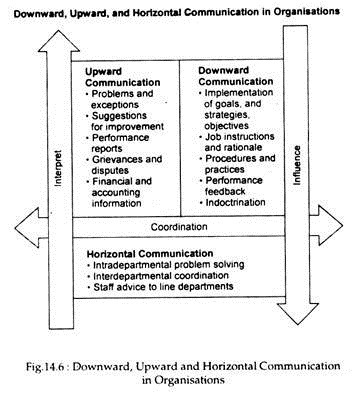

To understand organisational communication we have to examine the basic directions in which it moves. Formal communication channels are largely dictated by the structure of the organisation. Alternatively, they are prescribed by some other formal means. As Fig, 14.5 shows three basic communication channels are: vertical (upward and downward), horizontal (central) and diagonal.

Downward Communication:

Downward communication occurs when information flows down the hierarchy from superiors to subordinates. The superior may be assigning jobs or passing along needed information. In some cases, the manager may transmit so much information that subordinates suffers from role overload.

In other situations, the manager may fail to pass on important information, and as a result subordinations cannot do their jobs effectively. The solution is to transmit just the right amount of information — neither too much nor too little. Such a balance is often difficult to achieve.

Vertical Communication:

Vertical communication is said to occur when information flows between a subordinate and a manager. Such communication may involve only two people, or it may flow through several different levels in the organisation. And it may flow both up and down the organisation.

(a) Upward Communication:

Formal upward communications comprise messages that flow from the lower to the higher levels in the hierarchy of an organisation. They normally take the form of progress or performance reports and requests for resources and typically be viewed as a feedback of data or information from lower levels to upper management levels.

Upward communication includes oral, written and nonverbal messages from subordinates to superiors. Typically, this flow is from a subordinate to his(her) direct superior, then to that person’s direct superior, and so on through the hierarchy. Occasionally, however, a message might by-pass a particular superior.

Building healthy channels for upward communication is no doubt a painful and complex exercise. Still most organisations take pains to build such channels. As commented by Dafts: “Employees need to hear grievances, report progress, and provide feedback on management initiatives. Coupling a healthy flow of upward and downward communication insures that the communication circuit between managers and employees is complete.”

Upward communication is more subject to distortion than downward communication. Subordinates are prone to withholding or distorting information that makes them look bad. The greater the degree of difference in status between superior and subordinate and the greater the degree of distrust, the more likely the subordinate is to suppress or distort information.

Five types of information communicated upwards are the following:

1. Progress and performance (reports):

This is perhaps the best form of upward communication. These messages include periodic reports that pass on relevant information to the notice of management on how individuals and departments are actually performing (functioning). Example: “We completed the audit report of Jenson & Nicholson on schedule but on the Tata Chemicals report we are one week behind.”

2. Problems and exceptions:

These messages describe serious problems with and exception to routine performance in order to make senior managers aware of problem areas. Example: “The printing machine has been out of operation for three days; it will take at least a week to repair it and put it in a running condition.”

3. Ideas & Suggestions for improvement & problem solving:

These messages are ideas for improving task-related procedures to improve quality or enhance efficiency. Example: “I feel step 2 in the audit procedure should be dropped because it takes a lot of time and hardly produces any positive result.”

4. Requests for financial and accounting assistance and information:

These messages pertain to costs, accounts receivable, sales volume, anticipated profits, return on investment, and other matters of interest to top-level managers. Example: “Costs are 5% over the budget, but sales are 11% ahead of target, so the profit picture for the third quarter is quite impressive.”

5. Expression of attitudes, feelings, grievances and disputes that influence performance both directly and indirectly:

These messages are employees complaints and conflicts that travel up the organisational hierarchy for a hearing and possible resolution. Example: “The operations research manager cannot get the cooperation of the TISCO plant for the study of machine utilisation.”

From the organisation point of view, ‘open door’ policy, grievance system, attitude surveys or employee-management councils are all designed to provide upward communication to senior (top) management.

Most progressive organisations put considerable effort to facilitate upward communication through such devices as suggestion boxes, employee surveys, open-door policies, management information system reports, and face-to-face conversations between workers and executives.

In spite of all these efforts, however, barriers to accurate upward communication exist. It will be observed in this article that managers may resist hearing about employee problems, or employees may not trust managers sufficiently to push information upward.

(b) Downward communication:

Research that has been conducted on networks suggests some interesting connection between the network and performance. For example, when the group’s task is relatively simple and routine, the more centralised networks tend to perform with greater efficiency and accuracy.

The dominant leader facilitates performance in this structure by coordinating information flow. When a group is logging incoming invoices and distributing them for payment, for example, one centralised leader can coordinate things efficiently. When the task is complex and non-routine, such as making a major decision about organisational strategy, decentralised networks tend to be more effective.

This is because open channels of communication permit more interaction and a more efficient sharing of relevant information. Managers should recognise the effect of communication networks on group and organisational performance and should try to structure such networks accordingly.

This type of communication normally follows the organisation’s chain of command from top to bottom. In other words, it reflects and follows the typical authority-responsibility relationships depicted in the organisation chart.

A few example of downward communication are:

1. Information related to policies, procedures, rules, objectives and other types of plans.

2. Work assignments and directives.

3. Feedback on performance.

4. General information about the organisation such as its progress or status.

5. Specific requests for information from lower levels.

Downward messages may be in either of two forms: Written or oral. They are usually transmitted through diffusion board memos, report or other documents, conferences, meetings and speeches and interactions between small groups or between one person and another.

The traditional focus of management is on downward communication. Management has concentrated most of its effort on this type of communication. (But results achieved so far have not been really effective).

The most familiar and obvious flow of downward communication is the messages and information sent from top management to subordinates in a downward direction. The president of TISCO, for instance, sends bulletins to his vice-presidents, who, in turn, send memos to their subordinates. Management in modern organisations communicate downward to employees through such devices as speeches, messages in company publications, information leaflets inserted into pay envelopes, material on bulletin boards, and policy and procedure manuals.

Typically downward communication in an organisation encompasses the following topics:

Implementation of goals, strategies and objectives:

Communicating new strategies and goals provides information about specific targets and expected behaviours. It gives direction for lower levels of the organisation.

Example – “The new quality campaign is for result. We must improve quality if we have to survive.”

1. Job directives and rationale:

These are instructions on how to do a specific task and how the Job relates to other organisation activities. Example: “The purchasing department should order for steel now so that the construction work force can start construction of office building in a week’s time.”

2. Procedures and practices:

These are messages defining the organisation’s policies, rules, regulations, benefits, and structural arrangements. Example “After your one full year of employment, you are eligible to enroll in our company-sponsored salary savings plan.”

3. Performance feedback:

These messages appraise how efficiently individuals and departments are doing their work. Example: “Your aggressive salesmanship has greatly improved the sales of our new product — Raja Pressure Cookers.”

4. Indoctrination:

These messages are designed to motivate employees to adopt the company’s mission and cultural values and to participate in special ceremonies, such as picnics and cultural programmes. Example: “The company considers its employees as family and would like to invite everyone to attend the annual function on May 14.”

In this context R. L. Dafts has pointed out that “although formal downward communications are a powerful way to time a message is passed (transmitted) from one person to the next. In addition, the message can be distorted if it travels a great distance from its originating source to the ultimate receiver.”

(c) Horizontal (or lateral) Communication:

Whereas vertical communication involves a superior and a subordinate, horizontal communication involves colleagues and peers. For example, the production manager might communicate to the marketing manager that inventory levels are running low and that projected delivery dates should be extended by two weeks. Horizontal communication probably occurs more among managers than among non-managers.

It is the diagonal exchange of messages across peers or co-workers, both within and across departments. Thus, it is of two broad categories: (a) communication among peers within the same work group and (b) communication that occurs between and among departments on the same organisational level. The basic purpose of such communication is not only to inform but to request support and coordinate activities.

Three major types of such communication are:

1. Intradepartmental problem solving:

These messages take place between members of the same department and concern task accomplishment. Example: “Mr. Khanna, can you help us figure out how to complete the medical expense report form?”

2. Intradepartmental co-ordination:

Inter-departmental messages facilitate the accomplishment of joint tasks or projects. Example: “Mr. Banerjee, please get in touch with market and production departments and arrange a meeting to discuss the specifications for the new sub assembly. It seems that we may not be in a position to meet their requirements”.

3. Staff advice to line departments:

These messages are usually transmitted from specialists in functional areas such as operations research, finance or computer science to managers seeking assistance in these specialised areas. Examples: “Let’s have a word with the manufacturing supervisor about the problem he’s having interpreting the computer reports”.

Most organisations build in horizontal communications in the form of task forces, committees, liaison personnel, or even a matrix structure to encourage coordination. Thus, this form of communication is essentially coordinative in nature and is the result of specialisation in organisations. See Fig. 14.6 which is self-explanatory. It shows the interaction among the three types of communication.

The implication is that if one is to function effectively in his own job, he will most likely need to interact with, and be dependent on, other units within the organisation. Additionally, modern organisations today seek to use abilities of specialists by creating special project teams, task forces (e.g., the matrix form of organisation), or committees that pull together representatives from various specialities. Communication helps to coordinate these lateral activities.

Communication among peers and colleagues serves a number of purposes. First, it facilitates coordination among interdependent units. If unit A provides input for unit B (sequential interdependence), the supervisor of unit A might let the supervisor of unit B know in advance when the anticipated workload for the next day is going to be especially light or heavy so that he or she can plan accordingly. Horizontal communication can also be used for joint problem-solving, as when two plant managers of a large manufacturing firm get together to work out ways to improve productivity. Finally, horizontal communication plays a major role in matrix structures and in committees with representatives drawn from several departments.

(d) Diagonal Communication:

Finally, a passing reference may be made to diagonal communication. Such communication includes that which cuts diagonally across an organisation’s chain of command. It mainly results from line and staff department relationships. Wide-ranging forms of such communication are observed — from a purely advisory staff relationship to one in which staff exerts strong functional authority over line.

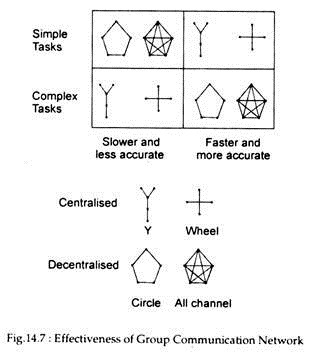

7. Communication in Groups:

Organisational communication most frequently occurs within groups and departments. Since employees work together to accomplish tasks, the group’s communication structure influences not only group communication normally but focuses on two characteristics: the extent to which group communication are centralized and the nature of the group’s task. Fig.14.7 illustrates the relationship between the two characteristics.

The group communication network may be either centralised or decentralised. The former refers to a group communication structure in which members communicate through a particular individual to arrive at a decision or to solve a problem.

On the contrary, the latter refers to a group communication structure in which group members communicate quite freely with one another to make decisions collectively. Members process information equally among themselves until there is a consensus on a particular decision.

Certain laboratory experiments have been carried out on group communications. It was discovered that “members could simply pass relevant information to a central person for a decision. Decentralised communications were slower for simple problems because information was passed among individuals until someone finally put the pieces together and solved the problem. However, for same complex problems, the decentralised communication network was faster.”

The reasons are easy to find:

(1) Since all necessary and relevant information was not restricted to a single individual, a pooling of information through widespread communications provided greater input into the decision.

(2) Likewise, the accuracy of problem solving was related to the complexity of the problem.

In most laboratory experiments, the centralised networks committed fewer errors on simple problems but more errors a complex ones. In truth, decentralised networks were less accurate for simple problems but more accurate for complex ones.

Empirical studies have also revealed a close relationship between communication and task complexity. It has been found that when the complexity of the departmental task is high, a decentralised communication process, in which all members share information for problem solving purposes, works best.

However, since the research and development and strategic planning departments involve complex tasks, these should be organised for decentralized communications. On the contrary, for simple and routine departmental tasks, such as for assembly line workers in an automobile plant or bank cashiers, communication can be centralized to a single person for efficient problem solving and decision-making.

Organisational design:

Finally, one may note that group communication processes are likely to have several implications for the design of organisational departments.

Two important points may be noted in this context:

1. Firstly, groups dealing with difficult, non-routine problems usually need a free flow of communication in all directions. So it is essential to encourage members to discuss problems with one another as also to devote a large percentage of employee time to information processing.

2. Secondly, groups performing routine tasks normally spend less time for information processing. The implication of this is that communication can be centralized. In such circumstances it is possible to channel data to a supervisor for decisions, freeing workers to spend a greater percentage of time on task activities.

8. Managing the Communication Process:

Given the obvious importance of communication in organisations, it is vital for managers to understand how best to manage the communication process. By this we mean that managers should understand how to maximise the potential benefits of communication and minimise the potential problems.

The importance of communication in modern organisations can hardly be overemphasized. This is why mangers usually spend a considerable portion of their time to communicate with others. But research has pointed out that almost 75% of all business communication fails to achieve the desired objectives. Certain external forces (which are beyond the control of a firm or its management) render communication ineffective.

There are, in fact, a number of barriers to effective communication. There are many road blocks that can interfere with effective communication. They interrupt or block communication or prevent mutual understanding.

Several factors may disrupt the communication process or serve as barriers to effective communication. One common problem is lack of credibility. Credibility problems arise when the sender is not considered a reliable source of information.

He (she) may not be trusted or may not be perceived as knowledgeable about the subject at hand. When a manager makes several wrong decisions, the extent to which they will be listened to and believed thereafter diminishes.

Reluctance may occur for various reasons. A manager may be reluctant to transmit downward information that he (she) knows is unpopular or that will cause negative reactions. A subordinate may be reluctant to transmit information upward for fear of reprisal or because it is felt that such as effort would be futile.

Two attributes of the received that may impede effective communication are poor listening habits and the predisposition to think in a certain set way.

Some people are poor listeners and may not comprehend part or all of the message. Receivers may also bring certain predispositions to the communication process. They may already have their minds made up, firmly set in a certain way.

Sometimes problems develop because attributes of the sender conflict with those of the receiver. That is, communication is disrupted by the interaction of sender and receiver attributes. Four of these interactions involve semantic problems, status differences, power differences, and perceptual differences.

Environmental factors may also disrupt effective communication. Noise may affect communication in various ways. Likewise, overload may be a problem when the receiver is being sent more information than he (she) can effectively handle.

So there are numerous barriers to communication. Some barriers arise in interpersonal, face to face communications while others are unique to organisational structures.

These can be divided into two broad categories:

(1) Organisational barriers, and

(2) Individual barriers.

In other words, barriers to communication can exist within the individual(s) or as part of the organisation.

Organisational Barriers:

It is necessary to note at the outset that organisations, by their very nature, tend to inhibit effective communication.

Five organisational barriers are:

1. Status and Power Differences:

It is noted that when an organisation starts growing, its structure expands, creating various communication problem. If a message has to pass through added (new) levels, it will obviously take long time to reach its destination and will tend to get distorted on the way. This is caused by the problem of status and power differences.

As Dafts has commented: “Low-power people may be reluctant to pass bad news up the hierarchy, thus giving the wrong impression to upper levels.” In a like manner, high-power people may not pay attention or may feel that low-status people have hardly anything to contribute.

Power differences often do disrupt communication. The marketing manager may have more power than the human resource manager and consequently may not pay much attention to a staffing report submitted by human resource department.

Similarly, communication problems may arise when people of different status try to communicate with each other. The company president may not pay much attention to a suggestion from an operating employee. Similarly, when the president goes out to inspect a new plant, workers may be reluctant to offer suggestions because of their low status.

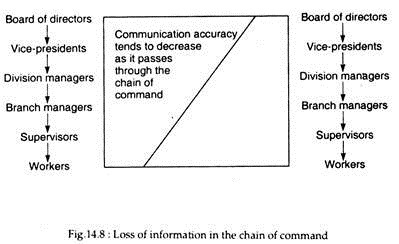

Fig.14.8 shows that as a message goes up or down through organisational levels, it passes through several ‘fitters’, each with its own perceptions, motives, needs and relationships with the nature of the message.

As each level in the communication chain can add to, take from, modify, or completely change the intent of a given message, there will be loss of information in the chain of command.

One proximate reason for this seems to be that messages are usually broader and more general at higher levels of management. As Chester Barnard has noted: “It follows that something may be lost or added by transmission at each stage of the process……. Moreover, when communications go from high positions down they often must be made more specific as they proceed.”

2. Managerial Unanimity:

Authority is a necessary feature of any representative organisation. It is not possible to accomplish much without certain persons having the right to make decisions. Yet the basic fact that one person supervises others creates a barrier to free and open communication.

3. Specialisation:

Specialisation is no doubt a part of organisational life. But it is not an unmixed blessing. It often tends to separate people even when they work side by side. The performance of difference functions, the pursuance of special interests of subgroups, use of different technical terms frequently prevent any commonality of feeling, make understanding very difficult, create strains between individuals and departments, act as barriers to communication and lead to errors.

In the words of Dafts: “Differences across departments in terms of needs and goals interfere with communications. Each department perceives problems in its own terms.” The production department, for instance, is concerned with production schedules and may not fully appreciate the need for and urgency of the department to supply the product in the market as quickly as possible.

Likewise, the specialised jargon (or technical vocabulary) of the engineering department may make it difficult for engineers to communicate with less educated foremen on the shop floor.

4. Lack of Channels:

Additionally, lack of adequate formal channels reduces communication effectiveness. It is of considerable importance for organisations to provide adequate upward, downward, and horizontal communication in the form of employee surveys, open door policies, newsletters, memos, task forces, and liaison personnel. In the absence of such formal channels, it is not possible for the organisation as a whole to communicate.

5. Mismatch between Communication Flow and Organisation’s Tasks:

Finally, it may be noted that the communication flow may not fit the group’s or organisation’s task. As Dafts has noted: “If a centralized communication structure is used for a non-routine task, there will not be enough information circulated to solve problems. When a decentralised, wide open communication style is used for solving simple tasks, excess communication takes place. The organisation, department or group is most efficient when the amount of communication flowing among employees fits the nature of the task.”

6. Perpetual Differences:

If people perceive a situation differently, they may also have difficulty in communicating with one another. Two people often fail to communicate effectively if one has a positive impression and the other a negative one about the same problem or the same solution to a particular problem.

Individual Barriers:

Even in the absence of the above organisational barriers managers could find that their messages would became distorted. On most occasions miscommunications are caused not by organisational factors, but by problems of human and language imperfections.

Individual barriers are of the following four categories:

1. Interpersonal Barriers:

Such barriers include problems with emotions and perceptions held by group participation. Communication will be a hazardous task if, for instance, people are more concerned with their own feelings and emotions than with the people with whom they are communicating. Dafts has noted that “Rigid perpetual labeling or categorizing of others prevents modification or alteration of opinions. If a person’s mind is made up before the start of the communication process, communication will fail. Moreover, people with diverse backgrounds or knowledge may interpret communication in different ways.”

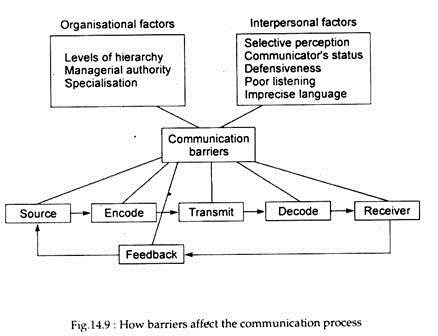

A deeper analysis reveals that there are five specific inter-personnel barriers to communication. These are discussed below (and illustrated in Fig. 14.9).

(a) Selective perception:

Perception is the complicated process through which we select, organize and give meaning to various occurrences. From experience we learn certain reactions: We expect a train when we hear a train whistle. One becomes defensive when called into the boss’s office.

Thus the expectations we have lead us to see events, people, objects and situations the way we want them to be. This is known as selective perception. It occurs because our perception is limited. A limiting factor is that one cannot grasp the whole of a stimulus at a given instant of time. Some parts of an event receive greater attention than others, and some receive no attention at all.

Another limiting factor seems to be that when one perceives an object or person, one’s evaluation is frequently coloured by the larger attributes of which that object or person is just a part. Thus, for instance, the way one perceives by boss’s messages is influenced not only by his relationships with the boss but also by his attitude toward management in general.

(b) Status of the communicator:

The second major inter-personal barrier to communication is the tendency to size up, evaluate, and weigh a message, in terms of sender’s credibility or ‘expertness’ in the subject area being communicated and on the degree of one’s influence or trust that the sender will communicate the truth.

In general, people in organisations accept a given message when they have confidence or a favourable attitude toward the sender. When they perceive managers as having a high credibility rating, subordinates are more likely to accept their messages, even blindly in some situations.

From this one can predict that “Managers must be viewed by their subordinates as credible and trustworthy. Otherwise, attempts to motivate, persuade, and direct the work efforts of subordinates are greatly handicapped from the very outset.”

(c) Defensiveness:

Another serious communicating feeling of defensiveness is on the part of a message sender, receiver or both. Thus when one person becomes defensive it finds expression in his(her) face, body movements and speech. This, in its turn, makes the other party equally, if not more, defensive.

Thus a defensive chain reaction is triggered. This defensive listening causes people to concentrate more on what they are going to say than on what they are hearing. When people feel defensive, they also distort what they do receive and are less likely to perceive accurately the motive, values and emotions of the receiver.

Since managers have status and can exercise control over situations they must be especially be aware of those situations that are likely to make subordinates feel defensive.

(d) Poor listening:

Since everyone in an organisation is always eager to defend his actions, both managers and employees resent un-favourable communication. Moreover, many supervisors avoid listening because they apprehend that they will get involved in the personal problems of a subordinate.

A poor reception or listening in one instance, however, is likely to affect a subordinate’s willingness to communicate job-related problems in the future. Moreover, listening being a time- consuming process, a manager, having too large a span of control, enjoys limited listening opportunities.

(e) Imprecise use of language:

Another barrier is created by the fact that all words that are used in organisations are not properly interpreted. Improper use of certain terms may also cause problems.

For example, a supervisor may instruct a subordinate to clear up the area (where a machine has been installed) before work starts. It is just five minutes’ job. The subordinate returns after one hour after cleaning up the entire floor, at the expense of a backlog of production work. Is it fair to blame the worker for the communication breakdown? Blaming the worker may simply protect the supervisor’s ego, but it represents a poor approach to a manager’s communication responsibilities.

2. Wrong Channel:

The second major communication barrier at the individual level is the selection of the wrong medium (channel) for sending a communication. If, for instance, a message is emotional it is better to transmit it face to face rather than in writing. On the contrary, for routine message, written notes prove most effective. But written notes lack the capacity for rapid feedback and multiple cues are needed for difficult messages.

3. Semantics:

The word ‘semantics’ refers to the meaning of words and way they are used. It often causes communication problems. Semantic problem arise when words have different meaning for different people. Words and phrases such as profit, increased productivity, retained earnings and return on investment may have positive meanings for managers but less positive (or even negative) meanings for labour. For example, an advertising effort may mean cost rise to a cost accountant but may imply more sales revenue to the marketing managers and more profit to the finance manager.

Likewise, the word ‘effectiveness’ may mean raising productivity of resources and cost reduction to a production superintendent but providing for employee satisfaction in the mind of a personnel staff specialist. Most words have diverse meanings. Thus communications must take care to select the appropriate words that will accurately encode ideas.

4. Inconsistency:

Finally, lack of consistency between verbal and nonverbal communications may cause problems. To be more specific, sending inconsistent cues between verbal and nonverbal communications will confuse the receiver.

If one’s facial expression does not match one’s words, the communication will contain noise and uncertainty. So it is absolutely essential that the tone of voice and body language is consistent with the words, and action should not contradict words.

Overcoming Communication Barriers:

Certain steps may be taken both at the individual and organisational levels to overcome the barriers discussed above. By overcoming these barriers greater communication effectiveness can be achieved. Managers can so design the organisation as to encourage positive, effective communication. Designing involves both organisational actions and individual skills.

To the extent possible, the sender should bear in mind four elements that can improve communication effectiveness: feedback, awareness, credibility and empathy.

9. Organisational Actions:

The following steps may be taken at the organisational level to improve the communication system:

1. Awareness of the need for Effective Communication:

It is necessary for managers to appreciate the important role that communication plays and then employ ‘communication specialists’. Their task is to help improve communicating by helping supervisors solve internal communication problems; devising company communication strategy regarding pay-off, plant closings or relocations, and terminations; and measuring, through interviews or surveys, the quality of communication efforts.

It is also necessary for top management to acknowledge the key communication linkage represented by first-line supervisors in their organisations. For, in the ultimate analysis, it is this level that works directly with the great bulk of operative employees.

2. Use of Feedback:

Another important means of improving the communication system is to use the feedback from messages sent. Feedback is facilitated by two-way communication, which allows the receiver to ask questions, request clarification and express opinions that let the sender know whether he(she) has been understood.

As a general rule, the more complicated the message, the more useful two-way communication is. Secondly, the sender should be aware of the meanings that different receivers might attach to various words. Thirdly, the sender may try to maintain credibility. Finally, the sender should be sensitive to the receiver’s perceptive and try to empathies with the receiver.

The techniques for receiving messages more effectively are to be a better listener and to be- sensitive to the sender’s perspective. Being an effective listener involves various things: not interrupting, putting the speaker at last, showing that the receiver is interested, not getting distracted, being patient and asking questions.

Being sensitive to the sender’s perspective, is not as trying to appreciate the sender’s position and to understand why he (she) might be sending a particular message. When, for instance, a subordinate receives bad news from a manager, the subordinate is likely to react with abruptness and hostility at first. After some time has lapsed, the nature of the subordinate will regain composure and the hostility will subside.

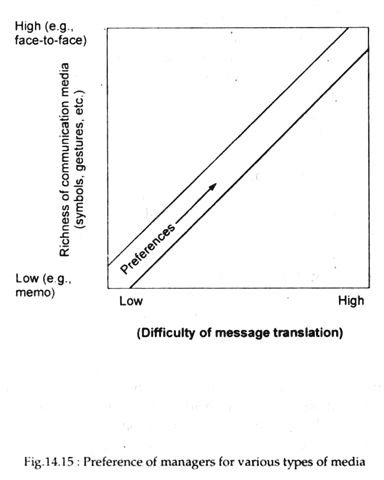

Three useful techniques can enhance communication effectiveness for both the sender and the receiver: following up (checking at a later time to be sure that the message has been received and understood), regulating information flow (the sender or receiver taking steps to ensure that overload does not occur), and both parties understanding the richness of different channels (media).

Here managers play a two-fold role to encourage feedback and use it effectively. Initially they can create a supportive environment that encourages feedback and can solicit feedback by their own actions thereafter.

(a) Creating an encouraging environment:

The way managers communicate with their subordinates determines largely, if not entirely, the amount of feedback they receive. The type of communication used and the communication environment are no doubt important in determining what feedback is obtained. But the responsibility for getting feedback goes much beyond these factors.

It is essential for managers to take an active role in soliciting feedback from others. At the same time managers, in their turn, must provide subordinates with .pertinent feedback. So it is a two-way traffic.

(b) Actively seeking feedback:

Participative management consists of two-way communication. This type of communication generates the best possible feedback. In fact, a manager who permits employees to make decisions or express opinions receives helpful responses from them which can be fruitfully utilized as a form of feedback that helps the manager better understand the employees’ thinking. Additionally, the opportunity to participate makes employees discharge a greater responsibility to ‘make things go right.’

A related point may be noted in this context. Most managers have a tendency to ignore feedback. This tendency increases when one finds himself in positions of power. Top level managers are, therefore, likely to have a stranger tendency than others to practise one-way communication.

3. Creating a Climate of Trust and Openness:

Perhaps the most important thing managers can do for the organisation is to create an organisational climate of trust and openness. This will undoubtedly encourage people to communicate honestly with one another. Subordinates are likely to feel free to transmit negative as well as positive messages without fear of retribution. In order to foster openness, honesty and trust, efforts must be made to develop interpersonal skills among employees.

4. Universal Use of Formal Channels:

It is also necessary for managers to develop and use formal information channels in all directions. Same companies use newsletters, others use daily training sessions at which managers address workers concerning the business. Other techniques are direct mail, bulletin boards and employee surveys.

5. Use of Multiple Channels:

It is also necessary for managers to encourage the use of multiple channels, including both formal and informal communications, such as written directives, face-to-face discussions, MBWA, and the grapevine. Sending messages through multiple channels enhance the chance that they will be properly received. In certain situations, it is desirable to by pass the formal channel and go directly to intended receivers.

6. Fitting the Structure for Meeting Needs:

Finally there is the need to fit the structure properly to meet communication needs. For instance, interdepartmental task forces can be created to overcome communication barriers among departments. The organisation can be so designed as to use teams, task forces, liaison personnel, or a matrix structure as needed to facilitate the horizontal flow of information for co-ordination and problem solving.

Moreover, the structure should be such as to reflect group information needs. When the task is highly complex it is necessary to implement a decentralised structure in order to encourage discussion and participation. In a routine department (such as the training department) the structure can be centralised with a single individual (the training officer) making most decisions.

10. Individual Skills Required for Communication:

Individual should develop the following skills:

1. Active Listening:

Perhaps the most important individual skill is active listening. Active listening is an important tool for achieving greater managerial effectiveness. Those managers who have this skill can do better than others.

It refers to such things as raising questions, showing interest and occasionally paraphrasing what the speaker has said to ensure that one is interpreting accurately. Active listening additionally implies providing feedback to the sender to complete the communication loop.

The most important listening technique which is used in practice is the use of reflective statements by the listener. Such statements demonstrate that the listener has heard what the sender said and bounces the communication ball back to the speaker.

However, this method is time-consuming. Secondly, subordinates, when permitted to open their mouths, may speak certain things which are discomforting or embarrassing.

2. Selection of Appropriate Channel:

Secondly, individuals must be competent enough to select the most appropriate channel for the messages. A rich channel (such as face-to-face discussion or telephone) should be used to send a complicated message. On the other hand memos, letters or electronic mail may be used to send routine messages because there is hardly any chance of misunderstanding.

3. Mutual Understanding:

Thirdly, it is of considerable importance for both senders and receivers to make a special effort to understand each other’s perspective. As Dafts put it, “Managers can sensitise themselves to the information receiver so that they will be better able to target the message, detect bias, and clarify missed interpretations. By understanding others’ perspectives, remarks can be classified, perceptions understood, and objectivity maintained.”

4. Wandering Around:

Finally the individual manager has to develop the skill of wandering around. Managers must be willing to get out of the office and check communication with others. Managers can develop an understanding of the organisation through direct observation and face-to-face meetings. This will enable them to communicate important ideas and values directly to other members in the organisation.

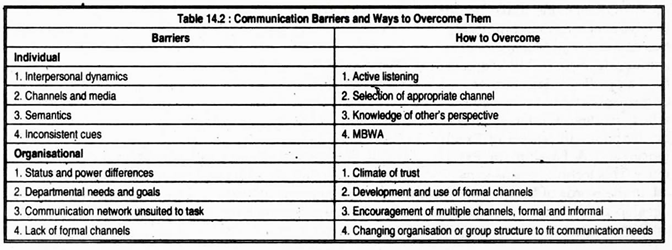

Table 14.2 below summarises the various barriers to communication and the steps that can be taken to overcame them.

11. Informal Communications:

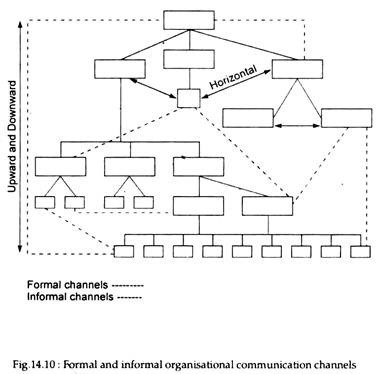

The nature of formal communication flows, i.e., the channels carrying messages have been designed by the organisation managers to carry job-related messages. But communication channels within an organisation, however, have an informal component. The latter is undoubtedly an important part of an organisation’s communication flow.

Informal communication channels refer to those channels which exist outside the formally authorised ones and do not adhere to the organisation’s hierarchy of authority. In fact, “informal- communications co-exist with formal communications but may skip hierarchical levels, cutting across vertical chains of command to connect virtually anyone in the organisation”.

This form of communicating serves a variety of managerial purposes. For example, the manager of a leading computer company in USA uses-informal channels by letting any employee reach him through his computer terminal. He also arranges wine and cheese get-together once a month (Friday afternoon).

The idea is to create an informal communication channel for employees. The idea is that over wine and cheese, employees are more willing to talk openly. In Fig. 14.10 we illustrate both formal and informal communications. It is shown that formal communications can be vertical or horizontal depending on task assignments and co-ordination responsibilities.

Purposes:

Informal communication channels serve four basic purposes:

1. They satisfy personal needs, e.g., relationships with others.

2. They counter the effects of boredom or monotony.

3. They attempt to influence the behaviour of others.

4. Finally, they serve as a source of job-related information that is not provided by formal channels.

Channels:

Most organisations make use of two types of informal communication channels: (a) Management by wandering around (MBA) and (b) the “grapevine”. The former is a communication technique in which managers interact largely by the books In Search of Excellence and A Passion for Excellence.

This technique is used by executives who talk directly with employees to learn what is going on. In the words of Dafts: “MBWA works for managers at all levels. They mingle with employees, develop positive relationships with them, and le^ directly from them about their department, division or organisation.”

However, the grapevine is the most well-known type of informal communication. It is twisted, tangled, and hard to follow but in practice it functions rapidly, selectively and effectively. The technique is so important that it demands detailed discussion.

The Grapevine:

Almost all organisations except the smallest have grapevines which are informal, person-to-person channels of communication network among individuals that are not officially sanctioned. However, grapevines do not always follow the same patterns as, nor do they necessarily coincide with formal channels of authority and communication.

Typically, the grapevine links employees in all directions, ranging from the president or chief executive through middle management, support staff and line employees. The grapevine is supposed to exist in an organisation all the time, but it can became a dominant force when formal channels are closed.

In such a situation, the grapevine actually becomes a service because the information it provides helps make an uncertain or unclear situation really meaningful. Employees using grapevine rumours to fill in information gaps are enabled to clarify management decisions. The grapevine tends to be more active during periods of change, excitement, anxiety, and economic depression.

Characteristics of Grapevines:

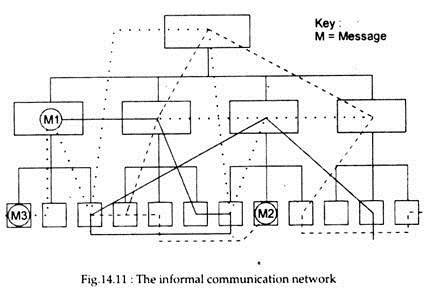

Fig. 14.11 illustrates several important characteristics of grapevines. Message 1 starts one level below the top of the organisation and flows from one person to another across the second and third levels of organisation, with the final recipient sending it down to a still lower (not shown in the Fig.14.11). Message 2 begins at the third level but follows a more complicated path as it flows through all three of the top levels of the organisation and is eventually transmitted outside to another organisation. Message 3 follows the most complicated path of all. It comes into the organisation from outside, travels through all three level and is transmitted to more than one person at a time.

In Fig. 14.11 some people receive all three messages, some receive only two and one manager does not receive any. Some people transmit the message to only one other person, whereas others tell more than one. This communication network seldom follows formal paths; some messages travel up, some down, some laterally, and still others diagonally. Obviously, the result is a complex messy pattern of communications.

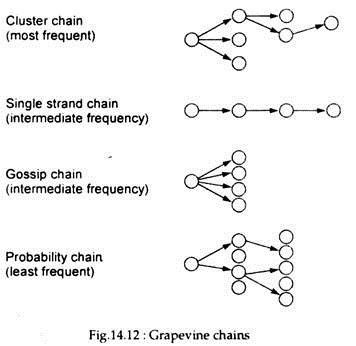

Keith Davis has identified four basic kinds of grapevines, as shown in Fig. 14.12. The least common grapevine is the probability chain. In this situation, people pass on messages to others on a random basis. This chain is likely to emerge when the information is of only passing interest and not really very important to anybody. The possibility of a manager in another organisation changing jobs might be transmitted through a probability chain.

The gossip chain occurs when one person spreads the message to as many others as possible. This chain is likely to carry personal information about such matters as divorces, births and love affairs.

Also of intermediate frequency is the single-strand chain, in which one person passes the information to only one other person. Accuracy of information suffers the most in this chain. The most common grapevine pattern is the cluster chain. One person passes the information to a selected few individuals some of whom pass it to a few other individuals while the others keep it to themselves.

Implications for Managers:

The manager has some control over the accuracy of information in the grapevine. By maintaining open communication channels and responding vigorously to inaccurate information, he(she) can help minimise the damage the grapevine can do.

In Griffin’s view:

“the grapevine can actually be an asset. By learning who the key people in the grapevine are, for example, the manager can partially control the information they receive and the grapevine to sound out employee reactions to new ideas such as a change in human resource policies or benefit packages. The manager can also get valuable information via the grapevine and use it to improve decision-making”.

In reality it is observed that a few people are primarily responsible for the success of a grapevine.

In the gossip chain, a single individual brings a piece of information to the notice of others. In a cluster chain, a few individuals each convey views to many others. The accuracy of grapevines depends on the fulfillment of one condition — having only a few people conveying information. Great distortion would occur if every person told one other person in sequence.

Merits:

Grapevines are not only accurate but highly relevant to the organisation. More than 75% of grapevine communications pertain to business-related topics rather-than personal, vicious gossip. Furthermore, about 70% to 90% of the details passed through a grapevine are accurate.

To prove the importance of grapevines, same researchers have deliberately planted a rumour in the organisation, and several hours later they passed out a questionnaire about the rumour. In this fashion they were enabled to find out such things as how many people passed on the rumour and how much distortion had occurred.

Another merit of grapevine is that it is highly selective, i.e., members of the grapevine filter out same information because of its sensitivity. For example, only two of 41 executives who had not been invited to a party given by the president of a company ever learned about it.

Thirdly, the grapevine is fast. The news that one executive had become a departmental head spread to 60% of the members of the organisation even within a few hours.

Demerits:

However, the grapevine frequently transmits incorrect information or unsubstantiated rumours, particularly during hours of crises or uncertainty or ambiguity. At such times management should guard against a grapevine that carries such inaccurate information that will only heighten anxiety.

Secondly, as the quantity of information on the grapevine increases, its accuracy tends to decline. And, in a crisis period, quantity tends to increase.

Thirdly, about 10-15% of the members of the organisation are active transmitters on the grapevine. Most members who receive information do not pass it on at all. What is more serious is that some individuals and groups are so divorced from the grapevine that they never receive any rumours.

On balance it seems that many managers would prefer to destroy the grapevine because they consider its rumour to be untrue, malicious, and harmful to personnel. Typically, this is not the case. However, managers have to be aware of the fact that almost 80 – 85% (or 5 out of every 6) important messages are carried to same extent by the grapevine rather than through official channels. Destructive rumours are likely to occur when official communication channels are closed.

In fact, a final aspect of the grapevine is the rumour network that extends beyond the organisation’s boundaries. Many of these rumours stop after being received by one or two people, but others spread to many people. And, of course, they may also be started by someone outside the organisation.

Rumours about impeding mergers, acquisitions or liquidations may affect share prices and credit standing. Even more damaging are rumours that undermine the public’s faith in an organisation. Some organisations have gone to the extent of hiring consultants or establish clinics or hot line numbers to squelch false rumours.