Here is a compilation of term paper topics on ‘Strategic Management’ especially written for college and management students.

Contents:

- Term Paper Topic on the the Strategy Hierarchy

- Term Paper Topic on the Process of Strategic Decision-Making

- Term Paper Topic on Strategic Dimensions of the Internet

- Term Paper Topic on Formulating Strategies of a Firm at the Business Level

- Term Paper Topic on the Organizational Structure of an Enterprise

- Term Paper Topic on the Product Divisional Structure of an Enterprise

- Term Paper Topic on the Geographic Divisional Structure of an Enterprise

- Term Paper Topic on the Matrix Structure of an Enterprise

- Term Paper Topic on Strategic Control through Performance

- Term Paper Topic on Strategic Control through Formal and Informal Organizations

Term Paper Topic # 1. The Strategy Hierarchy:

In most (large) corporations there are several levels of strategy. Strategic management is the highest in the sense that it is the broadest, applying to all parts of the firm. It gives direction to corporate values, corporate culture, corporate goals, and corporate missions. Under this broad corporate strategy there are often functional or business unit strategies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Functional strategies include marketing strategies, new product development strategies, human resource strategies, financial strategies, legal strategies, and information technology management strategies. The emphasis is on short and medium term plans and is limited to the domain of each department’s functional responsibility. Each functional department attempts to do its part in meeting overall corporate objectives, and hence to some extent their strategies are derived from broader corporate strategies.

Many companies feel that a functional organizational structure is not an efficient way to organize activities so they have reengineered according to processes or strategic business units (called SBUs). A strategic business unit is a semi-autonomous unit within an organization. It is usually responsible for its own budgeting, new product decisions, hiring decisions, and price setting. An SBU is treated as an internal profit centre by corporate headquarters. Each SBU is responsible for developing its business strategies, strategies that must be in tune with broader corporate strategies.

The “lowest” level of strategy is operational strategy. It is very narrow in focus and deals with day-to-day operational activities such as scheduling criteria. It must operate within a budget but is not at liberty to adjust or create that budget. Operational level strategy was encouraged by Peter Drucker in his theory of management by objectives (MBO).

Operational level strategies are informed by business level strategies which, in turn, are informed by corporate level strategies. Business strategy, which refers to the aggregated operational strategies of single business firm or that of an SBU in a diversified corporation, refers to the way in which a firm competes in its chosen arenas.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Corporate strategy, then, refers to the overarching strategy of the diversified firm. Such corporate strategy answers the questions of “in which businesses should we compete?” and “how does being in one business add to the competitive advantage of another portfolio firm, as well as the competitive advantage of the corporation as a whole?”

Since the turn of the millennium, there has been a tendency in some firms to revert to a simpler strategic structure. This is being driven by information technology. It is felt that knowledge management systems should be used to share information and create common goals. Strategic divisions are thought to hamper this process. Most recently, this notion of strategy has been captured under the rubric of dynamic strategy, popularized by the strategic management textbook authored by Carpenter and Sanders.

This work builds on that of Brown and Eisenhardt as well as Christensen and portrays firm strategy, both business and corporate, as necessarily embracing ongoing strategic change, and the seamless integration of strategy formulation and implementation. Such change and implementation are usually built into the strategy through the staging and pacing facets.

Term Paper Topic # 2. Process of Strategic Decision-Making

:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

How does one think and act strategically? Strategic decision-making is marked by four key distinctions. First, it is based on a systematic, comprehensive analysis of internal attributes and factors external to the organization, not just part of the organization. Second, it is long-term and future-oriented-usually several years to a decade or longer-but built on knowledge about the past and present. Third, it is distinctively opportunistic, always seeking to take advantage of favorable situations that occur outside the organization.

Finally, strategic thinking involves choices. Although making “win-win” strategic decisions is often possible, most involve some degree of trade-off between alternatives, at least in the short run. For example, raising salaries to retain a skilled workforce can increase wages, and adding product features or enhancing quality can increase the cost of production.

However, such trade-offs may diminish in the long run, as a more skilled, higher paid workforce may be more productive than a typical workforce, and sales of a higher quality product may increase, thereby raising sales and potentially profits. Decision-makers must understand the complex relationships among numerous factors across the business spectrum.

Because of these distinctions, strategic decision-making is generally reserved for the top executive and members of his or her top management team. The chief executive is the individual ultimately responsible (and generally held responsible) for the organization’s strategic management, but he or she rarely acts alone.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Except in the smallest companies, he or she relies on a team of top-level executives including members of the board of directors, vice presidents, and various line and staff managers-all of whom play instrumental roles in strategically managing the firm. Generally speaking, the quality of strategic decisions can improve dramatically when more than one capable executive participates in the process.

The size of the team on which the top executive relies for strategic input and support can vary from firm to firm. Centralized organizations generally involve fewer managers in strategic decisions than do decentralized ones. In addition, companies organized around functions such as marketing and production generally involve the heads of the functional departments in strategic decisions. Very large organizations often employ corporate-level strategic-planning staffs and outside consultants to assist top executives in the process.

The degree of involvement of top and middle managers in the strategic management process also depends on the personal philosophy of the CEO. Some chief executives are known for making quick decisions, whereas others have a reputation for involving a large number of top managers and others in the process.

Input to strategic decisions, however, need not be limited to members of the top management team. To the contrary, obtaining input from others throughout the organization, either directly or indirectly, can be quite beneficial. In fact, most strategic decisions result from the streams of inputs, decisions, and actions of many people. For example, an employee in a company’s research and development department may attend a trade show where a new product or production process idea that seems relevant to the company is discussed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The employee may relate the idea to his or her manager, who, in turn, may modify and pass it along to his or her manager. Eventually, a version of the idea may be discussed with the organization’s marketing and production managers, and later presented to top management.

The CEO will ultimately decide whether or not to incorporate the idea into the ongoing strategic planning process. This example illustrates the indirect involvement of individuals throughout the organization in the strategic management process. Top management is ultimately responsible for the final decision, but its decision is based on a culmination of the ideas, creativity, information, and analyses of others.

Ethics and social responsibility are also key concerns in strategic decision-making. Simply stated, the moral components and social outcomes associated with a strategic decision, such as the effects of closing an existing production facility in search of lower costs broad, should be considered alongside economic concerns. These issues are discussed in greater detail under the umbrella of strategy formulation.

Term Paper Topic # 3. Strategic Dimensions of the Internet:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

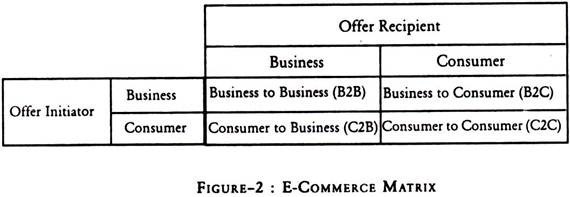

In addition to the movement towards di-aggreagtion and re-aggregation, the Internet has a number of characteristics closely associated with the strategic management process, the effects of which typically vary among industries.

1. Movement towards Information Symmetry:

Information symmetry occurs when all parties to a transaction share the same information concerning that transaction. Information symmetry is an underlying assumption of the economics- based models of “pure competition.” Information asymmetry-when one party has information that another does not-is the primary reason why many markets that might otherwise tend toward pure competition remain marginally competitive.

Businesses often seek to promote information asymmetry and utilize the information edge to their own advantage. Automobile retailers, for example, rarely post their absolute bottom line prices on their vehicles. Consumers are generally left to “haggle” with a number of dealers to estimate the true wholesale cost of the vehicle and the value of various options and accessories. The lack of consumer knowledge, as well as the lack of time and expertise required to obtain the information desired, results in higher selling prices for many of the retailers.

Following this example, the Internet provides a wealth of information to educate consumers. Independent vehicle test results, retailer web sites, wholesale costs for new vehicles, and estimated trade-in values are only a few mouse clicks away. Some consumers may end up purchasing a vehicle from a sponsor of an informational site, and even educated consumers who do not complete part or all of the transaction process online will likely force their traditional retailer of choice to negotiate in a more competitive manner.

2. Internet as a Distribution Channel:

The Internet acts as a distribution channel for non-tangible goods and services. Consumers can purchase items such as airline tickets, insurance, stocks, and computer software online without the necessity of physical delivery. For largely tangible goods and services, businesses can often distribute the “intangible portion” online, such as product and warranty information.

3. Speed of the Internet:

The Internet offers numerous opportunities to improve the speed of the actual transaction, as well as the process that leads up to and follows it. Consumers and businesses alike can research information 24 hours a day. Orders placed online may be processed immediately. Software engineers in the United States can work on projects during the day and then pass their work along to their counterparts in India who can continue work while the Americans sleep.

4. Interactivity of the Internet:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Internet provides extensive opportunities for interactivity that would otherwise not be available. Consumers can discuss their experiences with products and services on bulletin boards or in chat rooms. Firms can readily exchange information with trade associations that represent their industries. Users can share files with relative ease.

5. Potential for Cost Reductions and Cost Shifting:

The Internet provides many businesses with opportunities to minimize their costs both fixed and variable-and thereby enhance flexibility. Information can be distributed to thousands or millions of recipients without either the expense associated with the mail system or the equipment required to do so. The “virtual storefront” does not necessarily require an actual facility and may reduce transaction costs through automated online ordering systems, although this is not always the case.

Term Paper Topic # 4. Formulating Strategies of a Firm at the Business Level:

After a firm’s top managers have settled on a corporate-level strategy, at least in general terms, they need to focus on how the firm’s business (es) should complete. Whereas the corporate strategy concerns the basic thrust of the firm-where top managers would like to lead the firm- the business strategy addresses the competitive aspect- who the business should serve, what needs should be satisfied, and how a business develop core competencies and be positioned so that the customers’ needs as satisfied.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A business unit is an organizational entity with its own mission, set of competitors, and industry. A single firm that operates within only one industry is also considered a business unit. Strategic managers craft competitive strategies for each business unit to attain and sustain competitive advantage, a state whereby its successful strategies cannot be easily duplicated by its competitors. In most industries, a number of different competitive approaches can be successful, depending on the business unit’s resources.

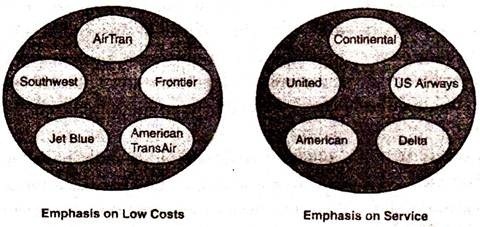

Although each business strategy is unique, strategies can be classified into a limited number of generic strategies based on their similarities. Generic strategies emphasize the commonalities among different business strategies, not their differences. Business adopting the same generic strategy comprises what is commonly referred to as a strategic group.

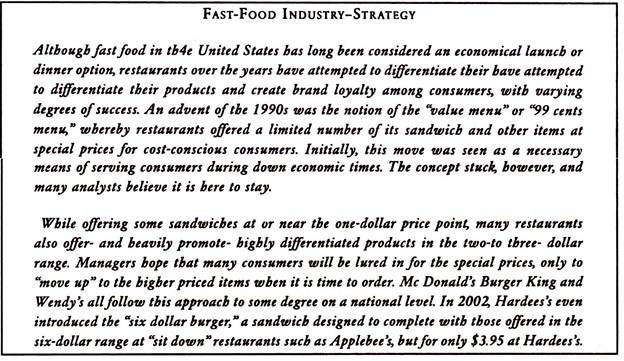

In the airline industry, for example, one strategic group may comprise carriers such as Southwest Airlines and Air Tran that offer low fares and no frills on a limited number of domestic routes, thereby maintaining their low cost structures price may traditional carriers such as Continental, United, and American that serve both domestic and international routes and offer extra services such as meals and movies on extended flights.

A new breed of fast-food restaurants is avoiding the value menu concept, however. High-end sandwich chains such as Paner Bread Company and Corner Bakery Cafe are sticking to a highly differentiated approach, emphasizing fresh bread and ingredients to an increasingly health- conscious market. The various strategic implemented by different, successful fast-food players demonstrate the number of viable market niches available in the industry.

Because industry definitions and strategy assessment are not always clear, identifying strategic groups within an industry is often difficult. Even when the industry definition is clear, an industry’s business units may be categorized into any number of strategic groups depending on the level of specificity desired.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There may also be one or two competitors that seem to be functioning between groups and are difficult to classify. For these reasons, the concept of strategic groups can be used as a means of understanding and illustrating competition within an industry, but the imitations of the approach should always be considered.

The challenging task of formulating and implementing a generic strategy is based on a number of internal and external factors. Selection of the generic approach is only the first step in formulating a business strategy. It is also necessary to fine-tune the strategy and accentuate the organization’s unique set of resource strengths.

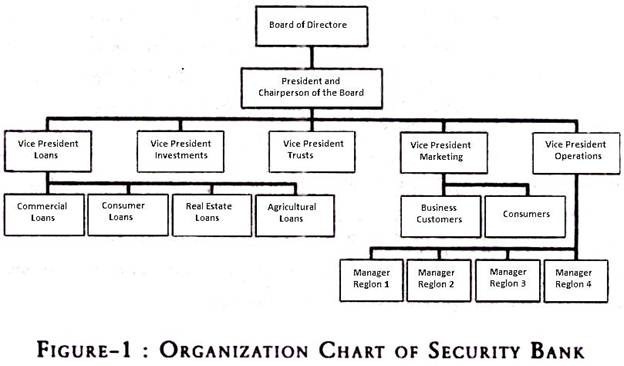

Term Paper Topic # 5. Organizational Structure of an Enterprise:

Although some new businesses are launched on a large scale, many start small with an owner/manager and a few employees. Neither an organizational chart nor a formal assignment of responsibilities is necessary. Each employee often performs multiple tasks, and the owner/manager is involved in all aspects of the business, a form of organization often called a “simple structure.” Early survival depends on an increase in demand for the company’s products or services.

As the organization grows to meet this demand, more permanent division of labor forms. The owner/manager, who once was nearly involved in all functions of the enterprise, begins to play more of a leadership role, and additional employees are assigned to more specialized functions. At some point, however, top management must evaluate the effectiveness of the evolving system of coordinating tasks and consider modifying it-if necessary-to facilitate implementation of the firm’s strategy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Organizational structure refers to the formal means by which work is coordinated in an organization. Simply stated, the structure exists to provide control and coordination for the organization. As such the structure designates formal reporting relationships and defines the number of levels in the hierarchy. There are logical reasons for organizing work along various lines.

For example, work can be organized along function so employees can work only in their areas of specially, by product so decisions about products can be made in an integrated fashion, and along geographical lines so decisions can be tailored to unique needs of various geographical regions. It is also reasonable to assume that individuals can and should work across the structure when necessary. Nonetheless, there is no single best structure, and the one selected for any organization will have its own set of benefits and challenges. Interestingly, many large, well-known companies change structures frequently as their environments change.

i. Vertical Growth:

The growth of the organization expands its structure, both vertically and horizontally. Vertical growth refers to an increase in the length of the organization’s hierarchy (i.e., levels of management). The number of employees reporting to each manager represents that manager’s span of control. A tall organization is composed of many hierarchical levels and narrow spans of control, whereas a flat organization has few levels in its hierarchy and a wide span of control from top to bottom. In reality, organizations fall somewhere in between the two extremes. Hence, organizations are seen as being “relatively tall” or “relatively flat.”

According to John Child, the average number of hierarchical levels for an organization with 3,000 employees is seven. Consequently, one might consider such an organization with fewer than seven hierarchical levels to be relatively flat, and one with more than seven to be relatively tall.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Because tall organizations have a narrow span of control, managers in such organizations exercise a relatively high degree of control over their subordinates, and authority tends to be relatively centralized. Conversely, authority is more decentralized in relatively flat structures because managers have broad spans of control and must therefore grant more flexibility to their employees. Because decisions are more likely to be made at lower levels in flat organizations, it is advisable for employees to have a more generalist orientation.

Strategically speaking both organizational types possess certain advantages. Tall, centralized organizations foster more effective coordination and communication of the business’s mission and goals to all employees. Planning and its execution are relatively easy to accomplish because all employees are centrally directed. As such, tall organizational structures may be best suited for environments that are relatively stable and predictable, although a number of experts have begun to suggest that tall structures do not yield the advantages today that they once did.

Flat structures also have their advantages. Administrative costs tend to be less than those in taller organizations because fewer hierarchical levels require fewer managers and support personnel. Decentralized decision-making also gives managers at various levels more authority, which may increase their satisfaction and motivation. The greater freedom in decision-making also encourages innovation. Hence, flat structures are best suited to more dynamic environments, such as those in which most Internet businesses operate. Quality tends to improve when decision-making is decentralized closest to the level at which the decisions will be implemented.

ii. Horizontal Growth:

Horizontal growth refers to an increase in the breadth of an organization’s structure. The owner/manager end a few employees may perform all of the functions in a new business. With growth, however, each function expands so that no one individual can be involved in all of the company’s functions, and the structure of the organization is broadened to accommodate the development of more specialized functions. Owners and managers who are unable to “let go” of former realms of responsibility as their ‘responsibilities increase are often referred to disparagingly as “micromanagers.”

Increases in organizational size usually lead to additional organizational layers and bureaucracy. Over time a large firm may become both less efficient and less capable of meeting the net is and expectations of its customers. Top management often responds by instituting a more horizontal structure-one with fewer hierarchies.

The organizational restructuring so pervasive throughout the 1980s and 1990s has often involved forming a more horizontal structure through downsizing, whereby one or more hierarchical levels- typically middle managers- are eliminated. Additionally, employee layoffs often occur in order to cut costs and eliminate some of the bureaucracy that invariable accompanies multiple organizational layers. As layers are reduced, decision -making becomes more decentralized.

Interestingly, downsizing often does not achieve the desired results, especially in the long term. Most studies suggest that only about one half of downsized firms actually lower costs, and many of these firms also suffer declines in productivity. When cuts are applied equally to all departments, both efficient and inefficient ones lose employees without regard to performance level when buyouts are offered to relatively high-paid, long-time employees, the firm can be faced with a drastic loss of critical experience.

In addition the positive changes in the formal organization created by downsizing often lead to dysfunctional consequences in the informal organization. Survivors (i.e. employees who remain after the cuts) are typically less loyal to the organization and wonder if they will be cut next. Hence, downsizing is a viable strategic alternative, but one whose long-term ramifications must be seriously considered before it is adopted.

Firms occasionally seek to downsize for the specific purpose of eliminating pat of the workforce so that it can be rebuilt in a different manner. A downsizing may occur after an acquisition if there are substantial cultural differences between the two firms and the acquiring firm wishes to reorient the new combined workforce.

Term Paper Topic # 6. Product Divisional Structure of an Enterprise:

The product divisional structure divides the organization’s activities into self-contained entities, each responsible for producing, distributing, and selling its own products. This structure often adopted when a businesses has several distinct product lines. For example a software developer may organize along three product lines business, productivity, and educational applications. Each division would have its own functional areas, such as R&D, marketing, and finance. The product divisional structure is used both in manufacturing and service organizations.

The product divisional structure has a number of advantages. Rather than emphasizing functions, the structure emphasizes product lines, resulting in a clear focus on each product category and a greater orientation toward customer service. Pinpointing the responsibility for profits or losses is also easier because each product division becomes a profit center-a well-defined organizational unit headed by a manager accountable for its revenues and expenditures.

The product divisional structure is also ideal for training and developing managers because each product manager is, in effect, running his or her “own business.” Hence, product manager-develop general management skills-an end that can be accomplished in a functional structure only by rotating managers from one functional area to another.

The product divisional structure also has its disadvantages. Because product divisional firms generally lave multiple departments performing the same function, the total personnel expense for manufacturing is likely to be higher than if only one department were necessary.

The coordination of activities at headquarters also becomes more difficult, as top management finds it harder to ensure consistency among the various departments. This problem can become substantial in large organization with 40 or more product divisions. Finally, because each product manager emphasizes his or her own product area, product managers tend to compete for resources instead of working together in the best interest of the company.

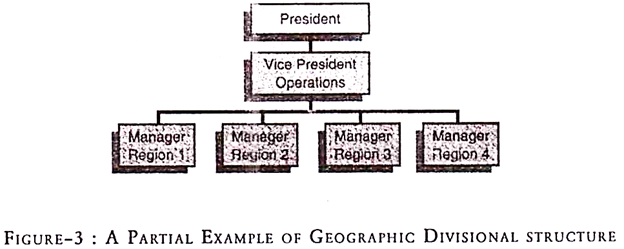

Term Paper Topic # 7. Geographic Divisional Structure of an Enterprise:

When a firm’s operations are dispersed through various locations, top executives often employ a geographic divisional structure) where ‘y activities and personnel are grouped by specific geographic locations. This structure may be used on a local basis (i.e., a city may be divided into sales regions) on a national basis (i.e., southern region, mid-Atlantic region, Midwest region or even on an international basis (i.e., North American region, Latin American region, Asian Region, Western European region). The primary impetus for the geographic divisional structure is the existence of two or more distinct markets that can be segmented easily along geographical lines.

There are two key advantages to organizing geographically. First, products and services may be tailored more effectively to the legal, social, technical, or climatic differences of specific regions. For example, relatively small 220-volt appliances may be appropriate for parts of Asia where living quarters tend to be limited and the American 110-volt system is not used. In addition, insurance companies are often organized along state and nation boundaries because of legal differences. Second, producing or distributing products in different locations may give the organization a competitive advantage. Many firms, for example, produce components in countries that have a labor cost advantage and assemble them in countries with an adequate supply of skilled labor.

The disadvantages of a geographic divisional structure are similar to those of the product divisional structure. Often, more functional personnel are required because each region has its own functional departments. Coordination of company-wide functions is often more difficult, and area managers may emphasize their own geographic regions to the exclusion of a companywide viewpoint.

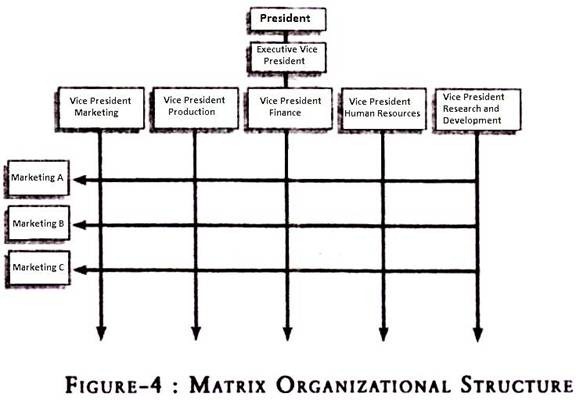

Term Paper Topic # 8. Matrix Structure of an Enterprise:

In a general sense, the functional and divisional structures-both product and geographical-can be viewed as opposites on ends of a continuum. The traditional demands for quality and price may pull an organization toward the functional end, whereas demands for service and speed may pull the organization toward the divisional end. To address these demands, to managers may settle on one of the two poles or may attempt to position the organization between the extremes. One such approach that has gained considerable popularity in recent years is the matrix structure.

Unlike the other structures that are characterized by a single chain of command, the matrix structure is a combination of the functional and product divisional structures. Hence personnel within the matrix have two (or more) supervisors- a “functional boss” and a “project boss.” In one project, a project manager might pull together some members of the organization’s functional departments. After the project is completed, the personnel in the project return to their functional departments. Hence, some individuals may be assigned to more than one team at the same time.

The matrix structure is most commonly used in organizations that operate in industries with a high rate of technological change, such as software development, management consulting, and telecommunications. Because of its complexity, the matrix structure is seen only in a relatively small number of organizations, such as engineering and interior design firms. However, recent developments in network technology have helped managers in many matrix organizations overcome some of the confusion and duplication that can accompany the structure. As such, matrix approaches are likely to continue to expand, especially in industries governed by technology.

A variation to the traditional project form of the matrix structure is reflected in the form of organization pioneered by Procter & Gamble (P&G) in 1927. At P&G, rather than a project manager being in charge of a temporary project, each of P&G’s individual products has a brand manager. Like a project manager, the brand manager pulls various specialists, as they are needed, from their functional departments.

Each brand manager reports to a category manager, who is in charge of all related products in a single category. The category manager coordinates the advertising and sales efforts so that competition among P&G products is minimized. Interestingly, P&G continues to modify its brand management approach as the environment changes, and has recently undergone a shift toward a more global orientation.

The matrix structure offers four key advantages. First, by combining the functional and product divisional structures, a firm can enjoy many of the advantages of both forms. Second, a matrix organization is flexible because employees may be transferred with ease between projects with different time frames. Third, a matrix permits lower-level functional employees to become heavily involved in projects and gain valuable experience. Finally, top management in a matrix is freed from day-to-day involvement in the operations of the enterprise in order to focus on strategic leadership.

The matrix also has a number of disadvantages First, because coordination across functional areas and across projects is so important, matrix personnel spend considerable time in meetings exchanging information, ultimately growing the bureaucracy and raising personnel costs. Second, matrix structures are characterized by considerable conflict, both between project and functional managers over budgets and personnel, and among the project managers themselves over similar resource allocation issues. Finally, reporting to two managers simultaneously violates a basic premise of management (i.e., each employee should report to only one boss) and can create role conflict when different bosses provide conflicting instructions.

Term Paper Topic # 9. Strategic Control through Performance:

Control through performance occurs by comparing the company’s profitability or market share growth to others in the market place. For example, the collective market share for cable television providers consistently declined throughout the 1990s. A number of cable customers switched to less expensive satellite providers such as DirecTV and Dish Network. By the early 2000s, cable’s competitive advantage of simplicity and complete local network programming had eroded in light of the satellite providers ability to offer small, easy-to install, and discreet satellite dishes and include local networks as part of the service plan. As a result, a number of cable companies began cutting rates in 2002 in an effort to regain lost market share.

Because individual measures of performance can provide a limited snapshot of the firm, a number of companies have begun using a balanced scorecard approach to measuring performance, whereby measurement is not based on a single quantitative factor, but on an array of quantitative and qualitative factors, such as return on assets, market share, customer loyalty and satisfaction, speed, and innovation. The key to employing a balanced scorecard is to select a combination of performance measures tailored specifically to the firm. This approach has helped a large number of firms better understand performance issues.

The PIMS program provides a broad range of benchmarks against which a firm’s performance can be compared. Top managers may also monitor the price of the company’s stock as relative price fluctuations suggest how investors value the performance of the firm. A sudden drop in price makes the firm a more attractive takeover target, whereas sharp increases may mean that an investor or group of investors is accumulating large blocks of stock to engineer a takeover or a change in top management.

Term Paper Topic # 10. Strategic Control through the Formal and Informal Organizations:

Strategic control can occur directly through the formal organization (i.e., the organizational structure) or indirectly through the informal organization. The formal organization the official structure of relationships and procedures used to manage organizational activity-can facilitates or impedes a firm’s success. When an organization’s structure is no longer appropriate for its mission, strategic control can initiate a change. However, structural changes typically require changes in the reward system all well.

In the 1990s, a number of organizations shifted from functional or product divisional structures to matrix structures and experienced considerable unanticipated difficulty. Substantial structural changes cannot be easily implemented and typically require a large amount of training and development. Strategic managers at many of these firms underestimated the complications associated with transforming their organizational structures into a more complex matrix structure.

The informal organization refers to the norms, behaviors, and expectations that evolve when individuals and groups come into contact with one another. The informal organization is dynamics and flexible and does not require managerial decree to change. Simply stated, informal relationships can promote or impede strategy implementation and can play a greater role than the formal organization.

When top executives use the formal organization effectively, the informal organization tends to reinforce the formal organization and promote the same values. However, when the organization’s value system is unclear or even contradictory, the informal organization will ultimately develop its own, more consistent set of values and rewards. For example, every organization claims to reward high job performance. However, when promotions and pay increases go to individuals who have the greatest seniority (regardless of their level of performance), employees will lose motivation and develop their own set of informal rules concerning what will and will not be rewarded.

Management must recognize its limitations concerning the informal organization. Specifically, management can influence, but cannot control, the informal organization. The most effective means of influencing the informal organization is to develop and promote a formal organization that is consistent with the core values of the firm. The informal organization becomes dysfunctional when it develops means to address inconsistencies in the formal organization.

The relationship between the formal and informal organizations should not be underestimated. In general, any change in structure may also necessitate an appropriate modification in the organization’s reward system, so that the new forms of desired behavior will be properly rewarded. When management fails to align the formal organization’s reward systems with new expectations, the informal organization typically changes to counterbalance the inconsistencies.