Here is a compilation of essay topics on ‘Strategic Management’ especially written for college and management students.

Contents:

- Essay on the Influence of Industry Environment on Strategic Management

- Essay on the Influence of Internet on Strategic Management

- Essay on the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Model for Framing Strategies

- Essay on the Forces Affecting the Strategy of a Company

- Essay on the Formulating Strategies of a Firm at the Corporate Level

- Essay on the Functional Structure of an Enterprise

- Essay on the Focus of Strategic Control

- Essay on the Strategic Control Standards (Benchmarks)

- Essay on the Strategic Control through Competitive Benchmarking

Essay Topic # 1. Influence of Industry Environment on Strategic Management:

The roots of the strategic management field can be traced to the 1950s when the discipline was originally called “business policy.” Today, strategic management is an eclectic field, drawing upon a variety of theoretical frameworks.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Industrial organization (IO), a branch of microeconomics, emphasizes the influence of the industry environment upon- the firm, The central tenet of industrial organization theory is the notion that a firm must adapt to influences in its industry to survive and prosper; thus, its financial performance is primarily determined by the success of the industry in which it competes.

Industries with favorable structures offer the greatest opportunity for firm profitability. Following this perspective, it is more important for a firm to choose the correct industry within which to compete than to determine how to compete with a given industry. Recent research has supported the notion that industry factors tend to play a dominant role in the performance of most competitors, except for those that are the notable industry leaders or losers.

IO assumes that an organization’s performance and ultimate survival depend on its ability to adapt to industry forces over which it has little or no control. According to IO, strategic managers should seek to understand the nature of the industry and formulate strategies that feed off the industry’s characteristics. IO Because IO focuses on industry forces, strategies, resources, and competencies are assumed to be fairly similar among competitors within a given industry.

If one find deviates from the industry norm and implements a new, successful strategy, other firms will rapidly mimic the higher-performing firm by purchasing the resources, competencies, or management talent that have made the leading firm so profitable. Hence, although the IO perspective emphasizes the industry’s influence on individual firms, it is also possible for firms to influence the strategy of rivals, and. In some cases even modify the structure of the industry.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Perhaps the opposite of the IO perspective, resource-based theory views performance primarily as a function of a firm’s ability to utilize its resources. Although environmental opportunities and threats are important, a firm’s unique resources comprise the key variables that allow it to develop a distinctive competence, enabling the firm to distinguish itself from its rivals and create competitive advantage.

“Resources” include all of a firm’s tangible and intangible assets, such as capital, equipment, employees, knowledge, and information. An organization’s resources are directly linked to its capabilities, which can create value and ultimately lead to profitability for the firm. Hence, resource-based theory focuses primarily on individual firms rather than in the competitive environment.

According to contingency theory, the most profitable firms are likely to be those that develop a beneficial fit with their environment. In other words, a strategy is most likely to be successful when it is consistent with the organization’s mission, its competitive environment, and its resources. Contingency theory represents a middle ground perspective that views organizational performance as the joint outcome of environmental forces and the firm’s strategic actions.

Firms can become proactive by choosing to operate in environments where opportunities and threats match the firms’ strengths and weaknesses. Should the industry environment change in a way that is unfavorable to the firm, its top managers’ should consider leaving that industry and reallocating its resources to other, more favorable industries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Each of these three perspectives has merit and ‘has been incorporated into the strategic management process laid out in this text. The industrial organization view is seen in the industry analysis phase, most directly in Michael Porter’s “five forces” model. Resource-based theory is applied directly to tile internal analysis phase and the effort to identify an organization’s resources that could lead to sustained competitive advantage. Contingency theory is seen in the strategic alternative generation phase, where alternatives are developed to improve the organization’s fit with its environment. Hence, multiple perspectives are critical to a holistic understanding of strategic management.

Theories aside, the development and retention of competitive advantage are central to the strategic management process. If resources are to be used for sustained competitive advantage-a firm’s ability to enjoy strategic benefits over an extended period of time-those resources must be valuable, rare, not subject to perfect imitation, and without strategically relevant substitutes. Valuable resources are those that contribute significantly to the firm’s effectiveness and efficiency. Rare resources are possessed by only a few competitors, and imperfectly imitable resources cannot be fully duplicated by rivals. Resources that have no strategically relevant substitutes enable the firm to operate in a manner that cannot be effectively imitated by others, and thereby sustain high performance.

Essay Topic # 2. Influence of Internet on Strategic Management:

The rise of the Internet has greatly influenced the strategic management process. The Internet has provided a new channel of distribution, a more efficient means of gathering and disseminating strategic information, and a new way of communicating with customers. The most fundamental change, however, concerns the dramatic shifts in organizational structure and their influences on viable business models, that is, the mechanism(s) whereby the organization seeks to earn a profit by selling its goods. As John Magretta put it, “A good business model begins with an insight into human motivations and ends in a rich stream of profits.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Internet has unleashed a number of alternative business models, some successful and some not. A number of critics have challenged the notion that “new business models” are needed to compete in the “new economy.” For example, Michael Porter noted that, “many of the pioneers of Internet business… have competed in ways ‘that violate nearly every precept of good strategy… By ignoring strategy, many companies have undermined the structure of their industries and reduced the likelihood that they or anyone else will gain, a competitive advantage.” In essence, Porter and others have argued that the market forces that governed the traditional economy have not disappeared in the Internet economy. Hence, many of the dot-coms that failed in 2000 did not succeed because they discarded these rules, set out to write their own, and built bad business models.

Consider the business model of one short-lived dot-com. By early 2001, Cyberrebate’s had become a very popular Web site, offering rebates with every product, some for the full purchase price. Critics charged that such a business could not sustain itself by giving away merchandise. However, a small percentage (less than 10 percent, according to CEO Joel Granik) of customers failed to collect their rebates for merchandise typically priced several times the retail level, and many others converted to products whose rebates constituted only part of the purchase prices. Time will determine the viability of such alternative business models. In Cyberrebate’s case, the company filed for bankruptcy protection in May 2001.

Interestingly, the success or failure of a business model may be a function of factors such as time, technology, or implementation, details, not the quality of the idea itself. As such, some business models may not prove successful at first, but with minor changes may become successful in a future period. For example, the concept of purchasing” groceries online was originally unsuccessful, due to such factors as Web design, inefficient warehousing, and relatively high prices. By 2003, improvements in these areas, as well as technological advances and a more Internet-savvy consumer, sparked a turnaround among online grocers. Hence, the original model has been enhanced and is yielding positive results.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The failure of many do-coms notwithstanding, the Internet has spawned a key change in the structure of business. During the past two decades, organizations have engaged in a process economists refer to as “dis-aggregation and re-aggregation.” The economic basis for this transformation was proposed by Nobel Laureate Ronald Coase in what is called Coase’s law; A firm will tend to expand until the costs of organizing an extra transaction within the firm become equal to the costs of carrying out the same transaction on the open market. In other words, large firms exist because they can perform most tasks raw material procurement, production, human resource management, sales, and so forth-more efficiently than they would otherwise be performed if they were “outsourced” to the open market.

However, recent technological advances, most notably the development of the Internet, have reduced the costs of these transactions for all firms. As a result, progressive firms have placed less emphasis-on performing all of the required activities themselves and have formed partnerships-contractual relationships with enterprises outside the organization-to manage, many of the functions that were previously handled in-house. Whereas outsourcing refers to specific agreements associated with a single task, partnering implies a longer-term commitment associated with more complex activities.

It is difficult to overstate the effects that dis-aggregation and re-aggregation have had on business enterprises, and more specifically, the effort to manage them strategically. In many respects, a partner can be viewed as an extension of the organization. Partner capabilities and limitations are fast becoming as important as internal strengths and weaknesses. Although these changes are more pronounced in some markets than in others, the development of the Internet economy has significantly changed the nature of business in all industries. Although the strategic management process described herein is applicable to almost any organization, most successful companies have already developed a substantial presence on the Internet.

Essay Topic # 3. Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Model for Framing Strategies:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A firm’s strategic managers often have difficulty coordinating the activities of multiple business. Units, particularly when they are minimally related or not related at all. A number of corporate portfolio frameworks have been developed to provide guidelines for strategists. Although firm-specific conditions may require exceptions to the guidelines, these frameworks can provide an excellent starting point to consider strategy in firms with multiple business units. The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) original frameworks a widely cited approach.

BCG Growth-Share Matrix:

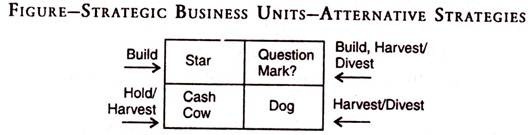

The BCG growth-share matrix was developed in 1996 by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) and is illustrated by the matrix. The market’s rate of growth is indicated on the vertical axis, and the firm’s share of the market is indicated on the horizontal axis. A firm’s business units can be plotted on the matrix with a circle whose size denotes the relative size of the business unit.

The horizontal position of a business indicates its market share and its vertical position depicts the growth rate of the market in which it competes. Managers and consultants can categorize each business unit as a star, question mark, cash cow, or dog, depending on each one’s relative market share and the growth rate of its market.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A star is a business unit that has a large share of a high-growth market, generally 10 percent or higher. Although stars are usually very profitable, they often necessitate considerable cash to continue their growth and to fight off the numerous competitors that are attracted to fast-growing markets. Question marks are business units with low shares of rapidly growing markets, and may be new businesses just entering the market. If they are able to grow and develop into market leaders, they evolve into stars; if not, they will likely be divested or liquidated.

A cash cow is a business unit that has a large share of a slow-growth market, generally less than 10 percent. Cash cows are normal, highly profitable because they often dominate a market that does not attract a large number of new entrants, Because they are well established, they need not spend vast resources for advertising, product promotions, or consumer rebates. The firm may invest the excess cash that they generate in its stars and question marks. Finally, dogs are business units that have small market shares in slow-growth (or even declining) industries. Dogs are generally marginal businesses that incur either losses or small profits, and are often liquidated.

Ideally, a well-balanced corporation should have mostly stars and cash cows, some question marks (because they can represent the future of the corporation), and few, if any, dogs. To attain this ideal, corporate level managers have four options. First, managers can build market share with stars and question marks. The key for question marks is to identify and support the promising ones so that they can be transformed into stars. Building market share may involve significant price reductions, which may result in losses or marginal profitability in the short run.

Second, management can hold market share with cash cows, thereby generating more cash than building market share does. Hence, the cash contributed by the cash cows can be used to support stars and those question marks deemed most promising.

Third, management may harvest, or milk as much short-term cash from a business as possible, usually while allowing its market share to decline. The cash gained from this strategy is also used to support stars and selected question marks. The businesses harvested usually include dogs, question marks that demonstrate little growth potential, and some weak cash cows.

Finally, management may divest a business unit to provide cash to the corporation and stem the outflow of cash that would have been spent on the business in the future. As dogs and less promising question marks are divested, the cash provided is reallocated to stars and more promising question marks.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

All things equal, healthy multi-business unit firms should maintain a balance of business units that generate cash and those that require funds for growth. Broadly speaking, business units below the dotted line are revenue generators, whereas business units above the dotted line are revenue users. The balance of businesses on both sides of the line can be a key factor in decisions to acquire new business unit or divest old ones.

The BCG matrix heavily emphasizes the importance of market share leadership as a precursor to profitability. Some question marks are cultivated to become leaders as well, but less promising question marks and dogs are usually targeted either for harvesting or divestiture.

The BCG matrix provides managers with a systematic means of considering the relationships among business units in its portfolio. A number of limitations of this and similar frameworks have been identified, however. For example, the BCG matrix assumes that success is directly linked to high performance, a relationship that often-but not always exists in a corporation.

The model also assumes that strategic managers are free to make portfolio decisions, such as transferring capital from cash cows to question marks, without challenges from shareholders and others. Hence, although the BCG matrix serves as an excellent starting point and generates discussion on critic strategy issues, it should not be interpreted literally.

Essay Topic # 4. Forces Affecting the Strategy of a Company:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Goals and Stakeholders:

Various stakeholders often have different goals for the firm. Each stakeholder group-including stockholders, members of the board of directors, managers, employees, suppliers, creditors, and customers-views the firm from a different perspective. Suggests what some of the goals might be for various stakeholders in a typical firm.

Although rationality suggests that stakeholders establish goals from the perspective of their own interests, it is easy to see how stakeholder goals can conflict with one another. For example, shareholders are generally interested in maximum profitability, whereas creditors are more concerned with long-term survival so that their loans will be repaid. Top management faces the difficult task of attempting to reconcile these differences while pursuing its own set of goals, which typically includes quality of work life and career advancement.

Influences on Goals:

Balancing the various goals of an organization’s, stakeholders can be a challenging task. For example, both top management and the hard of directors are primarily accountable to the owners of the corporation. As such, top management is responsible for generating financial returns, and the board of directors is charged with oversight of the firm’s management.

Some have argued, however, that this traditional shareholder-driven perspective is too narrow, and that financial returns are actually maximized when a customer driven perspective is adopted, a view that is consistent with the marketing concept. Consumer advocate and 2000 U.S. Presidential candidate Ralph Nader has argued for more than 30 years that large corporations must be more responsive to customer’s needs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Firms create value for various parties, including employees through wages and salaries, shareholders through profits, customers through value derived via its goods and services, and even governments through taxes. Corporations, however, should not seek to maximize the value delivered to any single stakeholder at the expense of those of other groups. Those that do so jeopardize their long term survival and profitability. For example, a firm that emphasizes the financial interests of shareholders over the monetary needs of employees can alienate employees, threatening returns in the long run.

Likewise, establishing long-term relationships with suppliers may restrict the firm’s ability to remain flexible and offer innovative products to customers. Top management is charged with the task of resolving opposing shareholder demands, recognizing that the firm must be managed to balance the demands of various stakeholder groups for the long-term benefit of the corporation as a whole.

2. The Agency Problem:

Ideally, top management should attempt to maximize the return to shareholders on their investment while simultaneously satisfying the interests of other stakeholders. However, for as long as absentee owners (i.e., the shareholders) have been hiring professionals to manage their companies, questions have been raised concerning the extent these managers actually place on maximizing financial returns. For this reason, it is not uncommon to see successful small partnerships seeking to stay small so the owner can remain personally in charge of the major business decisions.

The agency problem refers to a situation in which a firm’s managers-the “agents” of the owners- fail to act in the best interests of the shareholders. The extent to which the problem adversely affects most firms is widely debated, and factors associated with the problem can vary from country to country. Indeed, some argue that management primarily serves its own interests, whereas others contend that managers share the same interests as the shareholders.

3. Management Serves Its Own Interests:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to one perspective, top managers tend to pursue strategies that ultimately increase their own salaries and other reward In particular, top executives are likely to grow their firms because increases their rewards usually accompany increases in organizational size and its greater responsibilities, even if growth is not the optimal strategy for the firm. This perspective is based on the tendency for management salaries to increase as the organization grows.

Executives may also pursue diversification, the process of increasing the size of their firms by acquiring other companies that may or may not be related to the firm’s core business. Diversification not only increases a firm’s size but may also improve its survivability by spreading operational risks among its various business units.

However, diversification pursued only to spread risk is generally not in the best interest of shareholder, who always has the option of reducing their financial risks by diversifying their own financial portfolios. This perspective does not necessarily suggest that top management is unconcerned with the firm’s profitability or market value, but rather that top managers may emphasize business performance only to the extent that it discourages shareholder revolts and hostile takeovers.

4. Management and Stockholders Share the Same Interests:

Because manager’s livelihoods re-directly related to the success of the firm, one can argue that managers generally share the same interests as the stockholders. This perspective is supported a least in part by a number of empirical studies. One study, for example, found that firm profit- not size-is the primary determinant of top management rewards. Another point to a significant relationship between common stock earnings and top executives’ salaries. Hence, according to these studies, management rewards rise with firm performance, a relationship that encourages managers to be most concerned with company performance.

One of the most common suggestions for aligning the goals of top management and those of shareholders are to award shares of stock or stock options to top management, transforming professional manages, into shareholders. Stock option plans and high salaries may bring the interests of top management and stockholders closer together.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Top executives seek to protect their salaries and option plans and can do so only by delivering higher business performance. Indeed, research has suggested that as managerial stock ownership rises, the interests of managers and shareholders begin to converge to some extent. This view has gained support from others, but for different reasons.

Many suggest that managerial jobs contain structural imperatives that force managers to attempt to enhance profits. In addition, when mangers are major shareholders, they may become entrenched and risk averse, adopting conservative strategies that are beneficial to themselves but not necessarily to their shareholders.

In sum, the debate over whether top managers are primarily concerned with their firms’ returns or their own interests continue- Most scholars and practitioners believe both perspectives have merit, and pursue compensation models designed to bring the two sides together, such as those that emphasize stock options and profit sharing for managers instead of fixed pay levels. Many companies have adopted employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) to distribute shares of the company’s stock to managers and other employees over a period of time.

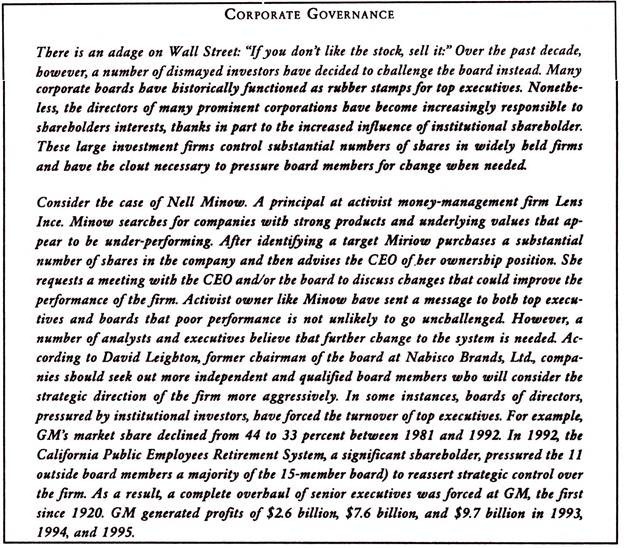

5. Corporate Governance and Goals of Boards of Directors:

Corporate governance refers to the board of directors, institutional investors (e.g., pension and retirement funds, mutual funds, banks, insurance companies, among other money managers), and large shareholders known as block holders who monitor firm strategies to ensure effective management. Boards of directors and institutional investors’ representatives of pension and retirement funds, mutual funds, and financial institutions are general y the most influential in the governance systems.

Boards of directors represent the shareholders and are legally authorized to monitor firm activities, as well as the selection, evaluation, and compensation of top managers. Because institutional investors own more than half of all shares of publicly traded firms, they tend to wield substantial influence. Block holders tend to hold less than 20 percent of the shares,’ so their influence is proportionally less than that of institutional investors.

Boards often include both inside (i.e., firm executives) and outside directors. Insiders bring company-specific knowledge to the board, whereas outsiders bring independence and an external perspective. Over the past several decades, the composition of the typical board has shifted from one controlled by insiders to one controlled by outsiders. This increase in outside influence often allows board members to oversee managerial decisions more effectively. Furthermore, when additional outsiders are added to insider-dominated boards, CEO dismissal is more likely when corporate performance declines and outsiders are more likely to pressure for corporate restructuring.

In the 1990s, the number of corporate board members with memberships in other boards began to increase dramatically. With outside directors of the largest 200 firms commanding are average of $152,000 in cash and equity in 2001, a number of companies became concerned about both potential conflicts of interest and the amount of the each individual can spend with the affairs of each company. As a result, many companies have begun to limit the number of board memberships their own be members may hold. By 2002, approximately two thirds of corporate board members at the largest 1,500 U.S. companies did not hold seats on other boards.

Boards of directors are composed of officials elected by the shareholders and are responsible for monitoring activities in the organization, evaluating top management’s strategic proposals, and establishing the broad strategic direction for the firm, although few board tend to ‘be aggressive in this regard. As such, boards are responsible for selecting and replacing the chief executive officer, establishing his or her compensation package, advising top management on strategic issues, and monitoring managerial and company performance as representatives of the shareholders.

A number of critic charges, however, that board members do not always fulfill their legal role. One reason is that board members are nominated by the CEO, who expects them to support his or her strategic initiatives. The generous compensation they 01 en receive is also a key issue.

When boards are controlled by insiders, a “rubber stamp” mentality can develop, whereby directors do not aggressively challenge executive decisions, as they should. This is particularly true when the CEO also serves as chair of the board, a phenomenon known as CEO duality. Although research has shown mixed results concerning the desirability of CEO duality, insider board members may be less willing to exert control when the CEO is also the chair of the board because present rewards and future career projects within the firm are largely determined by the CEO.

In the absence of CEO duality, however, insiders may be more likely to contribute to board control, often in subtle and indirect ways so as not to document any opposition to the decisions of the CEO. For example, the insiders may ostensibly present both side of various issues, while carefully framing the alternatives in favor of one that may be in opposition to the wishes of the CEO.

Pressure on directors to acknowledge shareholder concerns has increased over the past two decades. The major source of pressure in recent years has come from institutional investors, owners of large hunks of most publicly traded companies via retirement or mutual funds. By virtue of the size of their investments, they wield considerable power and are more willing to use it than ever before.

Some board members have played effective stewardship roles. Many directors promote strongly the best interests of the firm’s shareholders and various other stakeholder groups as well. Research indicates, for instance, that board members are often invaluable sources of environmental and competitive information. By conscientiously carrying out their duties, directors car ensure that management remains focused on company performance.

A number of recommendations have been made on how to promote an effective governance system. For example, it has been suggested that outside directors be the only ones to evaluate the performance of top managers against established mission and goals, that all outside board members should meet alone at least once annually, and that boards of directors should established appropriate qualifications for board membership and communicate these qualifications to shareholders.

For institutional shareholders, it is recommended that institutions and other shareholders act as owners and not just investor that they not interfere with day-to-day managerial decisions, that they evaluate the performance of the board of directors regularly, and that they should recognize that the prosperity of the firm benefits all shareholders.

6. Takeovers:

When shareholders conclude that the top managers of a firm with ineffective board members are mismanaging the firm, institution investors, block holders, and other shareholders may sell their shares, depressing, the market price of the company’s stock. Depressed prices often lead to a takeover, a purchase of a controlling quantity of a firm’s shares by an individual, a group of investors, or another organization.

Takeovers may be attempted by outsiders or insiders, and may be friendly or unfriendly. A friendly takeover is on in which both the buyer and seller desire the transaction. In contrast, an unfriendly takeover is one in which the target firm resists the sale, whereby one or more individuals purchase enough shares in the target firm to either force a changes top management or to manage the firm themselves. Interestingly, groups that seek to initiate unfriendly takeovers often include current or former firm executive.

In many cases, sudden takeover attempts rely heavily on borrowed funds to finance the acquisition, a process referred to as a leveraged buyout (LBO). LBOs strap the company with heavy debt and often lead to a partial divestment of some of the firm’s subsidiaries of product divisions to lighten the burden.

Corporate takeovers have been both defended and criticized. On the positive side, takeovers provide a system of checks and balances often required to initiate changes in ineffective management. Proponents argue that the threat of LBOs can pressure managers to operate their firms more efficiently.

Takeovers have beer- criticized from several perspectives. The need to pay back large loans can cause management to pursue activities that are expedient in the short run but not best for the firm in the long run. In addition, the extra debt required to finance an LBO tends to increase the likelihood of bankruptcy for a troubled firm.

Essay Topic # 5. Formulating Strategies of a Firm at the Corporate Level:

The first step in formulating an organization’s strategy is to assess the markets or industries in which the firm operates. At the corporate level, top management is charged with defining the corporate profile by identifying the specific business or industry in which the firm is and/or should be operating. Ideally, the corporate profile is a functional the firm’s particular strength and weaknesses, and the opportunities and threats (i.e., SWOT) posed by the external environment. A firm may choose three basic profiles to operate in a single industry, to operate in multiple related industries, and to operate in multiple, unrelated industries.

Most firm’s start as single-business companies, and many continue to thrive while remaining active primarily in one industry. Examples of such companies include UPS, Wal-Mart, Compaq, Campbell Soup, and McDonald’s. By competing only one industry, a firm can benefit from the specialized knowledge that it develops from concentrating its efforts and one business area.

This knowledge can help the firm improve product or service quality and become more efficient in its operations. McDonald’s, for instance, constantly changes its product line, while maintaining a law per-unit cost of operations by concentrating exclusively on fast food. Wal-Mart benefits from expertise derived from expertise derived from concentration in the retailing industry. Although involved in other businesses as well, Anheuser Busch limits its scope of operations primarily to brewing, from which it derives more than 80 percent of its revenues and profits.

Firms operating in a single industry are more susceptible to sharp downturns in business cycles. For this reason, mast firms eventually diversify and compete in more than one industry. Diversification allows a firm to raw, (potentially) uses its resources more effectively, and makes use of surplus revenues. Generally speaking, such firms may choose to compete in related or unrelated, industries.

Related diversification involves diversifying into similar businesses that may complement the original or primary business. Although diversification can reduce the uncertainty and risk associated with operating in, a single industry, participating in numerous unrelated businesses may result in un related associated with losing touch with the fundamentals of each business.

As a result, a number of scholars and executives occupy the “middle ground” by arguing that the aggregate uncertainty is minimized when a firm diversifies, but only into related industries. Relatedness, however, is ultimately “in the eyes of the beholder” and may be based on clear similarities such as product lines or customers or less obvious bases such as distribution channels or raw material similarities.

Unrelated diversification is driven by the desire to capitalize on profit opportunities in a given industry and involves the corporation in businesses that typically are dissimilar. Although such an approach may reduce risk fact of the firm, it also carries a number of potential disadvantages.

Because their interests are spread throughout unrelated business units, strategic managers may not stay abreast of market and technological changes that affect the businesses. In addition, they may unknowingly neglect the firm’s primary, or care, business in favor of one or more other units. Avoiding these pitfalls is easier when a firm’s business units are related.

The key to successful related diversification is the development of synergy among the related business units. The first step in the process is to identify the potential far a strong fit among the business units. Next, this fit should be parlayed into a competence that is difficult to imitate. Accomplishing this goal can be difficult when managers of the different business units do not share common cultural values.

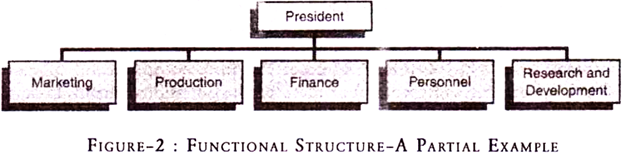

Essay Topic # 6. Functional Structure of an Enterprise:

The initial growth of an enterprise often requires that it be organized along functional areas. In the functional structure, each subunit of the organization engages in firm wide activities related to a particular function, such as marketing, human resources, finance, or production. Managers are grouped according to their expertise and the resources they use in their jobs. A functional structure has a number of strategic advantages.

Most notably, it can improve specialization and productivity by grouping together people who perform similar tasks. When functional specialists interact frequently, improvements and innovations for their functional areas may evolve that may not have otherwise occurred without a mass of specialists organized within the same unit. Working closely on a daily basis with others who share one’s functional interests also tends to increase job satisfaction and lower turnover. In addition, the functional structure can also foster economies of scale by centralizing functional activities.

Because of its ability to group specialists and foster economies of scale, this form tends to address cost and quality concerns well. However, the functional structure also has its disadvantages. Because the business is organized around functions rather than around products or geographic regions, pinpointing the responsibility for profits or losses can be difficult. For example, a decline in sales could be directly linked to problems in any of a number of departments, such as marketing, production or purchasing. Members of these departments may “point the finger” at other departments when firm performance declines.

In addition, a functional structure is prone to interdepartmental conflict by fostering a narrow perspective of the organization among its members. Managers in functional organizations tend to view the firm totally from the perspective of, their field of expertise. The marketing department might see a company problem as sales-related, whereas his human resource department might view the same challenge as a training and development concern.

In addition, communication and coordination across functional areas are often difficult because each function tend to have its own perspective and vernacular. R&D, for example, tends to focus on long-term issues whereas the production department generally emphasizes the short run. Grouping individuals along function minimizes communication across functions and can foster these types of communication problems.

In sum, the functional structure can serve as a relatively effective and efficient means of controlling and coordinating activities. However, there has been a growing emphasis on customer service and speed in recent years, challenges that the functional structure may not be as well equipped to address. Depending on the specific issues facing an organization, a division along product or geographical lines may be more appropriate.

Essay Topic # 7. Focus of Strategic Control:

The focus of strategic control is both internal and external because it is top management’s role to align the internal operations of the enterprise with its external environment. Relying on quantitative and qualitative performance measures, top management uses strategic control to maintain proper alignment between the external and internal environments.

Although individual firms usually exert little or no influence over the external environment, these macro environmental and industry forces must be continuously monitored because shifts in the macro environment can have strategic ramifications for the company. The purpose of monitoring the external environment is to determine whether the assumptions on which the strategy is based remain valid. In this context, strategic control consists of modifying the company’s operations to more effectively defend itself against external threats that may arise or become known.

Considering internal operations, top management must assess the strategy’s effectiveness in accomplishing the firm’s mission and goals- If the firm seeks to be the industry’s low-cost producer, for example, it managers must compare its production efficiency with those of competitors and determine the extent to which the firm is attaining its goal. In the broad quantitative sense, management must assess the strategy’s effectiveness in attaining the firm’s objectives. For example, management can compare a firm’s 3.7 percent market share with its stated objective of 4.1 percent to determine the extent to which its strategy is effective.

Firm performance may be evaluated in a number of ways. Management can compare current operating results with those from the preceding quarter or year. A qualitative judgment may be made about changes in product or service quality. Quantitative measures may also be used, including return on investment (ROI), return on assets (ROA), return on sales (ROS), and return on equity (ROE), and growth in revenues.

Essay Topic # 8. Strategic Control Standards (Benchmarks):

Profitability is the most commonly utilized performance measure and is therefore a popular means of gauging performance and exerting strategic control. A number of additional financial measures may also be helpful.

Control standards should be established for the internal factors identified in the previous step. However, the focus should not consider past performance. Doing so can be myopic because it ignores important external variables. For example, a rise in a business’s ROA from 8 to 10 percent may appear to be a significant improvement, but this measure must be evaluated in the context of industry trends.

In a depressed industry, a 10 percent ROA may be considered outstanding, but that same return in a growth industry may be disappointing if the leading firms earn 20 percent. In addition, an increase in a company’s ROA is less encouraging if performance continues to lag behind industry standards.

Often, strategic control standards are based or competitive benchmarking the process of measuring a firm’s performance against that of the top performers, usually in the same industry. After determining the appropriate benchmarks, a firm’s managers set goals to meet or exceed them. Best practices- processes or activities that have been successful in other firms-may be adopted as a means of improving performance.

i. PIMS Program:

The PIMS (profit impact of market strategy) program is a database that contains quantitative and qualitative information on the performance of thousands of firms and more than 5,000 business units. PIMS was developed in the 1960s as a result of General Electric’s efforts to determine which factors drive profitability in a business unit. GE’s top managers and corporate staff began to assess business unit performance in a formal, systematic fashion. In 1975, other companies were invited to join the project, and the Strategic Planning Institute was founded to manage the effort.

Each of the participating businesses provides quantitative and qualitative information to the program, such as market share, product/service quality, new products and services introduced as a percentage of sales, relative prices of products and services, marketing expenses as a percentage of sales, and research and development expenses as a percentage of sales.

Two profitability measures are used- net operating profit before taxes as a percentage of sales (ROS), and net income before taxes as a percentage of total investment (ROI) or of total assets (ROA). Participating firms have access to the data aggregate form (i.e., no specific entries from other firms), whereas only limited data is available to nonparticipating organizations. Interestingly, the PIMS studies found the market perceived quality relative to that of competitors was the single best predictor of market share and profitability.

Each of the PIMS variables has implications for strategic control. For example, top managers may discover that a business with low quality measures may also be spending substantially less in research. R&D efforts may be enhanced to address the discrepancy.

ii. Published Information for Strategic Control:

Fortune magazine annually publishes the most-and least-admired U.S. corporations with annual sales of at least $500 million in such diverse industries as electronics, pharmaceuticals, retailing, transportation, banking, insurance, metals, food, motor vehicles, and utilities. Corporate dimensions are evaluated along factors such as quality of products and services, innovation, quality of management, market share, financial returns and stability, social responsibility, and human resource management effectiveness.

Publications such as Forbes, Industry Week, Business Week, and the Industry Standard also provide performance scorecards based on similar criteria. Although such lists generally include only large, publicly traded companies, they can offer high-quality strategic information at minimal cost to the strategic managers of all firms, regardless of size. Published information on three measures- quality, innovation, and market share-can be particularly useful measures.

iii. Product/Service Quality:

Over the years” there has been a positive relationship between product/service quality-including both the conformance of a product or service to internal standards and the ultimate consumer’s perception of quality-and the financial performance of those firms. Conforming to Internet quality standards is not sufficient. Products and services must also meet the expectations of users, including both objective and subjective measures.

Fortune assesses quality by asking executives, outside directors, and financial analysts to judge outputs of the largest firms in the United States. Its studies consistently demonstrate a significant relationship between product/service quality and firm performance. Although the PIMS program assesses quality through judgments made by both managers and customer’s instead of asking executives and analysts, its findings also support a strong positive correlation between product quality and business performance.

Consumer Reports is also an excellent source of product quality data, evaluating hundreds of products from cars to medicine each year. Because Consumer Reports accepts no advertising, its evaluations are relatively bias free, rendering it an excellent source of product quality information for competing businesses. Even if the products of a particular business are not evaluated by this publication, that company can still gain insight on the quality of products’ and services produced by its competitors, suppliers, and buyers.

Specific published information may also exist for select industries. One of the best known is the “Customer Satisfaction Index” released annually by J. D. Power for the automobile industry. A survey of new-car owners each year examines such variables as satisfaction with various aspects of vehicle performance; problems reported during the first 90 days of ownership; ratings of dealer service quality; and ratings of the sales, delivery, and condition of new vehicles-. Numerous Internet sites-such as Virtual ratings(dot)com-offer quality ratings associated with a number of industries for everything from computers to university professors.

Broadly speaking, the Internet serves as an excellent resource for strategic managers seeking quality assessments for its industry. For example, a number of sites (e.g., www(dot)deal time(dot)com) provide consumer ratings of vendors. Although such information is not always reliable, feedback forums can provide strategic managers with valuable insight into the quality perceptions of their customers. Even Amazon(dot)com ranks all books on sales volume and provides opportunities for readers to post comment to prospective buyers.

iv. Innovation:

Innovation is a complex process and is conceptualized, measured, and controlled through a variety of mean. Some researchers use expenditures for product research and development and process R&D as a “surrogate” measure. Expenditures on developing new or improved products and processes also tend to increase the level of innovation, a finding also supported by PIMS data. However, it should not be assumed that all innovation-related expenditures yield the same payback.

Some firms plan and control their programs for innovation very carefully. 3M, for instance, has established a standard that 25 percent of each business unit’s sales should come from products introduced to the market within the past five years. Not surprisingly, 3M invests about twice as much of its sales revenue in R&D as its competitors. This approach is consistent with 3M’s differentiation and prospector orientation at the business level.

v. Relative Market Share:

Market share is a common measure of performance for a firm. As market share increases, control over the external environment, economies of scale, and profitability are all likely to be enhanced. In large firms, market share often plays an important role in manage rid performance evaluations at all levels in the organization. Because market share gains ultimately depend on other strategic variables, such as consumer tastes, product quality, innovation, and pricing strategies, changes in relative market share may serve as a strategic control gauge for both internal and external factors.

For successful smaller businesses, market share may serve as a strategic control barometer because some businesses may strategically plan to maintain a low market share. In this event, the strategic control of market share emphasizes variables that are not targeted. It growth and includes tactics that encourage high prices and discourage price discounts. Limiting the number of product/markets in which the company competes also serves to limit small market share.

A small market share combined with operations in limited product/markets may allow a company to compete in domains where its larger rivals cannot. Hence, for some companies, emphasizing increases in relative market share can trigger increases in cost or declines in quality and can actually be counterproductive.

Essay Topic # 9. Strategic Control through Competitive Benchmarking:

Realistic performance targets, or benchmarks, should be established for managers throughout the organization. At the organization level, factors such as profitability, market share, and revenue growth may be applied; the most appropriate performance benchmarks are those associates with the strategy’s success, and those over which the organization has control.

Benchmarks should also be specific. For example, if market share is identified as a key indicator of the success or failure of a growth strategy, a specific market share should be identified, based on past performance and/or industry norms. Without specificity, it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of a strategy after it is implemented if clear targets are not identified in advance.

Control at the functional level may include factors such as the number of defects in production or composite scores on customer satisfaction surveys. Like organization-wide benchmarks, functional targets should also be specific, such as “3 defective products per 1,000 produced” or “97 percent customer satisfaction based on an existing survey instrument.”

Generally speaking, corrective action should be taken at all levels if actual performance is less than the standard that has been established unless extraordinary causes of the discrepancy can be identified, such as a halt in production when a fire shuts down a critical supplier. It is most desirable for strategic managers to consider and anticipate possible corrective measures before a strategy is implemented whenever possible.