Here is a term paper on ‘Conflict in an Organization’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short term papers on ‘Conflict in an Organization’ especially written for college and management students.

Conflict in an Organization

Term Paper Contents:

- Term Paper on the Nature of Conflict

- Term Paper on Conflict due to Frustration

- Term Paper on the Role Conflict and Ambiguity

- Term Paper on Conflict Resolution

- Term Paper on the Transactional Analysis for Conflict Management

- Term Paper on Managing Organizational Conflicts: A Contingency Perspective

- Term Paper on Comparison among the Three Modes of Resolving Inter-Group Conflict

Term Paper # 1. Nature of Conflict:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Conflict arises from disagreement over the goals to attend all the method to use to accomplish them. In organisations conflict among different interest is inevitable and sometimes the amount of conflict is substantial.

Writer D.H. Stamatis in his book describe the nature of conflict: Conflict occurs when two or more parties in an organization have to interact to accomplish a task, make a decision, meet an objective, or solve a problem and the party’s interest class. Secondly one party’s actions cause negative reaction of the others and also parties who are unable to resolve controversy among themselves.

Productivity suffers as long as conflict remains unsolved. The party’s in conflict influence co-workers, who begin to take sides or withdraw with the situations. In the end conflict adversely affects not only productivity but also working relationship.

These two definitions are different from each other and share a common buyer:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

That conflict is an able and has a negative impact on individuals and organisations. On the other hand there are two kinds of conflicts. Conflict that cost very little and that which cost a great deal. Both cause disruption in an organisation and loss of productivity. Low cost conflict in contrast may be considered constructive controversy and out of such controversy new ideas and improvement arise.

Fred luthans describe the nature of conflict as interactive behaviour that can occur and the individual, personal, group or organizational labour. It often results in conflict at each of this levels. Although such conflict as intra individual conflict is very closely related to stress.

According to him conflict has been defined as the condition of inconsistencies between values or goals. Because deliberate behaviour coming in the way of goal achievement and in terms of hostility. Further conflict behaviour in terms of objective conflict of interest, personals styles, reaction to threats and cognitive distortions.

These intra individual conflicts steams from frustration, goal displacement and roles ambiguity. These conflicts are examining from the prospective of transitional analysis and the Johari Window.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Term Paper # 2. Conflict due to Frustration:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

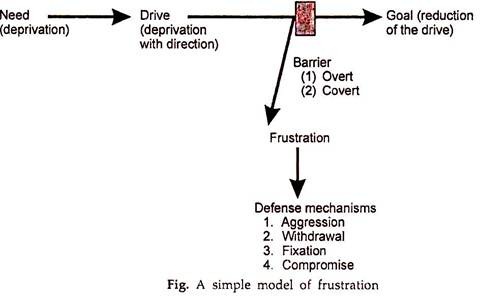

Frustration occurs when a motivated drive is blocked before reaching a desired goal. The following figure illustrates what happened. The barriers may be either overt (outward or physical) or covert (inward or mental socio psychological). Frustration normally triggers defence mechanism in the person.

Aggression has come to be viewed as only one possible reaction.

There are four broad category of mechanism:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Aggression,

2. Withdrawal,

3. Fixation and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. Compromise.

One example reveals that a frustrated person from the low educational background has intense need for pride and dignity might have frustration, if his needs are not fulfilled the drive set up to alleviate the need and accomplish the goal would throw a person in a feet of frustration.

In most of the cases frustration leave a positive impact on individual performance and organisational goal.

Goal Conflict:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Another common source of conflict for an individual is a goal which has both positive and negative feature or two or more competing the goal. But in frustration a single motive is brought before the goal is reached. In goal conflict two or more motives brought one another.

There are three separate types of goal conflict:

1. Approach-Approach Conflict.

Where the individuals are motivated to approach two or more positive but mutually exclusive goals.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Approach-Avoidance Conflict:

Where the individual is motivated to approach a goal and at the same time is motivated to avoid it. The single goal contains both positive and negative characteristics for the individual.

3. Avoidance-Avoidance Conflict:

Where the individual is motivated to avoid two or more negative but mutually exclusive goals.

To varying degrees, each of these forms of goal conflict exists in the modern organization.

Term Paper # 3. Role Conflict and Ambiguity:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Role Conflict and Ambiguity is closely related to the concept of norms. Role is defined as a position that has expectation evolving from establish norm. Most of the Role Conflict in an organization steam from expectation and demands of the person in the position. Generally we come across Role Conflict and Ambiguity in the position of a supervisor. His role is both a part of the management and one set of expectation of the role.

This set of expectation is exclusively based on his values and attitude but as a supervisor, he is to keep link between management and workforce. Conflict arises because of this dual position, he holds in the organizational setting.

Role Conflict: The Lesser of Two Evils:

Filly and House conclude after an extensive review of the research on organisational role conflict that it has undesirable consequences but may be the lesser of two evils. This conflict could easily be resolved by granting the final decision making authority.

Filly and House also report that research indicates the extent of the undesirable effects from role conflict depends upon four measure variables:

1. Awareness of role conflicts

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Awareness of conflicting job pressures

3. Ability to tolerate stress

4. General personality make up.

Term Paper # 4. Conflict Resolution:

Robert Blake and Jane Mouton have defined five methods of handling conflicts:

1. Avoidance,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Accommodation,

3. Competition,

4. Compromise, and

5. Collaboration.

1. Avoidance:

Avoidance is withdrawal from the conflict or failure to take a position on it. The employees involved make no attempt to understand or correct the cause of the conflict. The human resources manager, when asked to help resolve it, denies its existence.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Accommodation:

In accommodation, employees overlook their own concerns and allow the other employees involved in the conflict to obtain what is important to them. Differences are downplayed in the attempt to reach an agreement. The accommodating HR manager, concerned with a quick fix for the problem, rolls the issues together and decides what will be the best, most quickly achievable solution.

3. Competition:

In the competitive mode, a simple “win-lose” mentality prevails. Each employee strives to obtain his or her objectives, to win even at the expense of the other employee(s). The competitive HR manager called in to resolve a conflict, chosen an employee he or she believes should win and works to achieve a “victory” for that employee.

4. Compromise:

Employees using the compromise method are willing to give up part of their own objectives in order to resolve the conflict. Compromising HR managers obtain concessions from each employee and guide the negotiations until a settlement is reached. This settlement may not fully satisfy either employee, but both agree that it is the best resolution for the conflict.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

5. Collaboration:

During collaboration, a mutual problem is resolved. Each employee accepts the others’ objectives and they work together to achieve the best outcome for both. During the collaboration process, trust and openness are required because attempts are made to identify and resolve concerns underlying the conflict. Trust and openness, in turn, are increased through the process. The HR manager involved in a collaboration works along with the employees to find the best possible solution.

6. Before selecting a method of resolving a particular conflict, the HR manager must consider the nature of the conflict and the likely consequences of the solution.

7. Again, keep in mind that successful conflict resolution always benefits the organization. In general, collaboration and accommodation are desirable methods because they promote employee cooperation and harmony.

But because such methods may be time-consuming and may produce results that are not entirely satisfying to any of the employees involved, these methods are inappropriate in some cases.

Like “confrontation” is a word with a bad reputation. It conjures up image of one person shouting at another telling another person that “this is the last straw” and stomping away. But confrontation is also a learned, step-by-step process or sequence of events that is used by two parties who are in conflict and who are trying to resolve their differences.

Certain conditions contribute to the success of a confrontation:

1. At least one of the parties (or third party) is aware that a conflict exists.

2. One of the parties is willing to start the confrontation process.

3. Both parties are willing to use a clearly defined confrontation process and problem- solving framework (i.e., collaboration, compromise, etc.).

4. Both parties expect, or at least hope, that this process will resolve their differences.

The process of confronting a conflict involves six major steps:

Step 1: Awareness:

During the awareness step an individual or group (Party ‘A’) recognizes that a conflict exists between that individual or group and another party (Party “B”). (Party “A” recognizes a conflict with Party “B”).

Step 2: The Decision to Confront:

Party “A” decides the conflict is important enough to warrant a confrontation with Party “B” and that such a confrontation is preferable to avoid the concern.

Step 3: The Confrontation:

Party “A” decides to use the collaboration or comprise model and confronts Party “B”. At this point, Party “B” may indicate a willingness to accept the confrontation, or may attempt to deny the existence of the conflict or reduce its seriousness. Often, the conflict is resolved in this step. If not, both parties must proceed to Step 4.

Step 4: Determining the Cause of the Conflict:

The confrontation is most likely to succeed if parties “A” and “B” are specific about their grievances. The parties should try to describe their own feelings, opinions, reactions, and fears in relation to the conflict. A key objective of this step is determining the cause of the conflict. If the two parties cannot agree on the cause of the conflict, then the confrontation has failed.

Step 5: Determining the Outcome and Further Steps:

Upto this point, both parties have been involved in defining the problem and sharing information. In Step 5 the parties attempt to devise specific means of reducing or eliminating the cause of the conflict. If both parties agree on a solution, then the confrontation has been successful.

Step 6: Follow-Through:

After the solution has been implemented, both parties should plan regular checks at specific times in the future to ensure that their agreements are being kept.

A successful confrontation can have many positive outcomes for the parties involved and the larger organization: a good solution to a problem, increased work productivity, a raised level of commitment to decisions by both parties, a willingness to take greater risks in the future, and a more open and trusting relationship between the parties.

The collaboration process as well as the methods of conflict resolution described above, is primarily for use in solving conflicts between individuals or small groups. But conflicts also arise between much larger organizations; such conflicts, in fact, are quite common in today’s economy. (Labour disputes are a typical example.)

There are two basic strategies for resolving conflicts between large organizations. In both approaches a neutral third party acts as a mediator for the parties in conflict. In the first approach, an “interpersonal facilitator” plays this role. He or she meets not with the conflicting groups, but with an individual representative from each.

These representatives do not deal directly with each other, but communicate through the facilitator. The facilitator plays an active role in the resolution process by identifying areas of agreement as well as disagreement between the groups and guiding the representatives toward an acceptable solution.

The interpersonal facilitator’s functions include:

1. Building Anticipation:

Before holding any meetings with both representatives, the facilitator meets with each individually to prepare him or her to meet the opponent. Each representative is encouraged to be open-minded, positive, and constructive.

2. Controlling Discussions:

During meetings, the facilitator controls and directs the discussions and maintains order.

3. Reversing Antagonists’ Roles:

The facilitator helps each group’s representatives to express their anger and frustration in a constructive way, so tensions and tempers are defused.

4. Transmitting Information:

Often the facilitator acts as the “go-between” for the two representatives, passing information between them to prevent the resolution process from breaking down.

5. Formulating Proposals:

With the information obtained from the two representatives, the facilitator drafts possible solutions and presents them to the representatives.

The second strategy is called the “interface conflict-solving” approach. In this approach, the group members attend meetings and are actively involved in the process, and disputants deal with each other directly.

In this strategy, as in the first a neutral person helps the groups through a programme of steps that help them identify and resolve their differences. In this approach, however, this neutral third party plays a less active role. Instead, it is the representatives of the conflicting groups, called the facilitators, who lead the meetings and guide the groups toward as resolution.

The functions of these facilitators include:

1. Setting Expectations:

The facilitators describe the objectives and activities involved in each step of the programme to their respective groups’ members.

2. Establishing Round:

Establishing Round Rules for the General Sessions.

3. Determining Sequence:

The facilitators establish the sequence of speakers within their groups to maintain order during meetings.

4. Monitoring for Candor:

They encourage openness and participation by group members.

5. Curbing Open Expression of Hostile Attitudes between Groups:

The facilitators sometimes have to intervene to let their own groups’ participants know they are breaking the ground rules.

6. Avoiding Evaluation:

The facilitators direct but do not evaluate the progress or quality of the groups’ efforts by resolving the conflict.

7. Introducing Procedures to Reduce Disagreements:

When the groups reach an impasse, the facilitators should suggest way to break the deadlock.

8. Ensuring Understanding:

When members of a group have finished speaking, its facilitator should make sure the other group’s questions have been answered satisfactorily.

9. Following Up:

After a solution has been achieved, the facilitator should arrange follow-up meetings to ensure that the changes have been implemented.

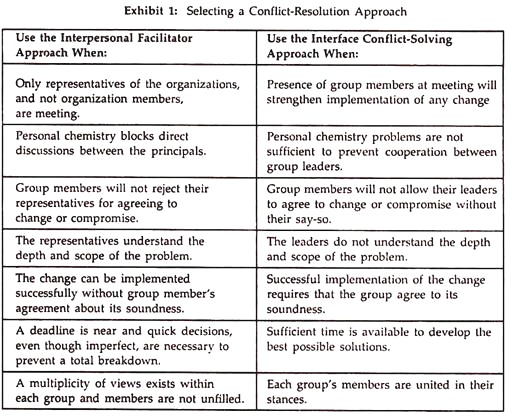

Exhibit 1 contrasts the circumstances when the interpersonal facilitator approach and the interface conflict-solving approach are most appropriate.

Conflicts, an inevitable part of life in the workplace, are generally regarded as a negative force that creates tension, lowers productivity, and disrupts employee relationships. As a result, human resources managers, who are frequently called upon to resolve employee conflicts, often regard them with dread. But for the human resources manager who learns to resolve them skillfully, conflicts can become, instead, welcome opportunities to improve and benefit the workplace.

Term Paper # 5. Transactional Analysis for Conflict Management:

Eric Berne and Games People play:

Following Alfred Adler in several ways, Eric Berne, a psychiatrist from San Francisco, also was rejected by traditional psychoanalysts; when he applied for membership in a psychoanalytical society he was not accepted. His revenge was inventing transactional analysis, or TA. Berne had his own weekly meeting (on Tuesday) or TA analysis which began at 8:30 in the evening (if you rang the bell at 8:20 according to one of his colleagues, the door remained shut) and finished at 10:00.

The experience of psychoanalysts seems to suggest that people function best in small groups of dedicated individuals. When the group members, who usually go through some form of baptism to gain admission, know enough, they go elsewhere to spread the word. This is good for the populace, who get a choice in terms of therapies, but bad for prophets and psychoanalysts.

Transactional analysis is a system of individual and social psychiatry which is concerned with the psychology of human relationships. In Games People play Berne describes 36 scripts people have devised to govern their transactions—the rules they play by. A typical game is “Courtroom”, in which the husband says to a third person something like, “What do you think she has done now? She did…….” And the innocent bystander pleads neutrality as the wife opens up with “This is the way it really was…………..”

In presenting the idea that people tend to spin out their lives by engaging in certain games, Berne strips the surface innocence of conventional relations and reveals what is simmering just below the surface in most human encounters. His penetrating and stimulating analysis takes as its starting point the idea of stimulus hunger—which he summarizes by noting, “If you are not stroked, your spinal cord will shrivel up,” He uses this term, stroke, to describe a social stimulus such as “Hello,” and defines a transaction as an exchange of strokes.

The Repertoire of Ego States: The Parent, the Adult, the Child:

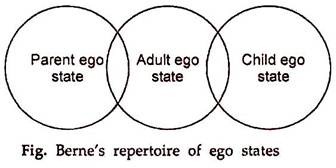

To explain games, Berne makes use of the idea that each individual has a limited repertoire of ego states.

There are three kinds of principal:

1. Ego states similar to those of the parental figure.

2. Ego states which are concerned with the objective appraisal of reality.

3. Ego states which are fixated in early childhood.

In talking about the Child ego state, Berne is careful to avoid the words childish and immature. In the Child are to be found intuition, creativity, and spontaneous drive and enjoyment. The Adult is essential for survival because of its reality-testing function, which enables it to process and analyze data and compute probabilities.

The Parent has two functions: It enables an individual to assume the role of parent, and it automates many decisions. According to Berne, these three aspects of personality are necessary for survival.

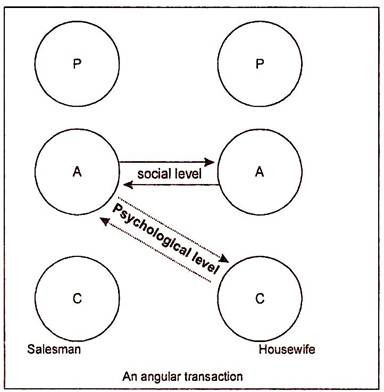

Sales people are professional games players, as the following example provided by Berne illustrates:

Salesman:

This one is better, but you cannot afford it.

Housewife:

That is the one I’ll take.

Analysis of this transaction is shown in figure. At the conscious, ostensible, social level,- the salesman (Adult ego) is stating two objective facts: “This one is better” and “You cannot afford it.” At the Adult level, the housewife should reply, “Right, both times.”

However, an ulterior or psychological vector was aimed at the housewife’s Child. The validity of the salesman’s judgment is vindicated by the Child’s response, which in effects is “Irrespective of cost, I’ll show you that I’m as good as anybody.”

Berne’s theory of games has considerable relevance for the student of organisational behaviour. For a start, Berne’s idea of stroking certainly has relevance to the way in which salutations are exchanged by executives.

Although Berne’s theory lacks theoretical consistency and has no considerable body of empirical data to lend it’s validity, it has considerable pragmatic relevance. A psychiatrist who re fete a troubled patient to the works of Freud, Jung, or Adler runs the risk of adding mental confusion to the patient’s other problems, but a copy of Games People Play may give the patient a valuable insight into her or his own personality dynamics. As a tool for analyzing organizational behaviour, it has considerable potential, to say nothing of the fun it is to use.

Thomas Harrs and I’m ok-You’re ok:

Dr. Thomas A. Harris, a psychiatrist, developed Berne’s ideas into a teaching and learning device which is of great interest to executives because of its simplicity and ease of understanding and the extent of its application to organizational problems. The device is transactional analysis (TA), the central thesis of which is that most people suffer from a vague sense of inferiority (they feel that they’re “not OK”).

Differing balances among these ego states result in four basic life positions:

1. I’m not OK—you’re OK (the anxious, dependent position).

2. I’m not OK—you’re not OK (the give-up position).

3. I’m OK—you’re not OK (the thug position).

4. I’m OK—you’re OK (the balanced, Adult position).

Transactional analysis can be taught to executives and other employees—and in spite of its simplifications, it is useful. For example, in the American Airlines training school for flight attendants, trainees spend a fair amount of time learning about ego states.

On the basis of the Berne gospel that people are divided into three types—the Parent, domineering and scolding; the Adult, reasoning and reasonable with; and the Child, creative and innovative but also likely to throw a tantrum or to sulk—the trainees are encouraged to covertly categorize their passengers and react accordingly. Having been introduced to the mysteries of Berne and Harris, they move on to learn TACT— transactional analysis and customer treatment.

Term Paper # 6. Managing Organizational Conflicts: A Contingency Perspective:

Like power and politics, conflict is also a largely negatively understood term. Most often, it is interpreted as a hindrance in the teamwork, which is supposed to be essential for achieving a common organisational goal. Correspondingly, management off conflicts is often equated with elimination or avoidance of conflicts. Responsible managers, it is assumed, must ensure that conflicts do not arise and harmony prevails.

This popular view (shared by many managers) was further strengthened in a study by Singh and Parthasarthy (1985). Based on the responses of 242 executives, they concluded that avoidance of conflicts and compromising when a conflict situation arises, appeared to be the most prevalent styles of conflict’ management among Indian executives.

Conflicts, however, are not always dysfunctional (even if they are uncomfortable). Boulding (1964) demonstrated that groups which contained deviant members who would challenge the established order, produced better ideas and more elegant solutions, than the perfectly harmonious groups (ironically, when asked to drop one group member, the groups ousted their deviant members, inspite of their positive value). Similarly, Pareek (1982) concluded that conflicts give impetus to richer exploration, more extensive debate and better solutions.

There are, admittedly, conflicts which can lead to disruption of organisational activities.

However, as Robbins (1987) noted:

“An organisation totally devoid of conflict is probably also static, apathetic, and nonresponsive to change. Conflict is functional when it initiates the search for new and better ways of doing things and undermines complacency within the organisation…. The manager’s job is to create an environment in which conflict is healthy but not allowed to run to pathological extremes.”

Related to this negative connotation attached to conflict is also the assumption that the best way of managing conflicts is through collaboration. Practising managers do realise that while collaboration may be an ideal worth striving for, it is often not the most feasible one in reality.

We will propose that, besides collaboration, there are also other strategies which can be effective and useful to manage conflicts in organisational situations. Derr (1978) proposed that besides collaboration, two other methods, bargaining and power- play, can be equally useful in managing conflicts, depending on the nature and context of conflicts. Moreover, organisations also use structural and procedural strategies to contain and resolve conflicts.

Term Paper # 7. Comparison among the Three Modes of Resolving Inter-Group Conflict:

A. Collaboration:

Collaboration is one of the most popularly recommended approach for managing conflicts. Most of the OD intervention techniques, in some way or the other, rely on establishing a collaborative climate among conflicting parties. It stands to reason also, that if people have problems with each other, the most rational and civilised way to deal with them is to understand each other’s point of view and to arrive at a mutually acceptable solution.

There are numerous advantages of using a collaborative approach to manage conflicts.

Some of the most significant ones are listed below:

1. Collaboration creates a climate of authentic and open interpersonal relationships among organisational members and sub-units. Such a climate is conducive to long- term smooth functioning of the organisation.

2. Collaboration is a problem-solving approach, and therefore, encourages more creative and innovative activities in the organisation.

3. Collaboration facilitates information flow and feedback processes in the organisation. In doing so, it also lays the foundations for the emergence of self-correcting mechanisms in the organisation.

4. Collaboration ensures long-term commitment of the organizational members to problem- solving, and thus, it also reduces the need for the introduction of more formal coordinating mechanisms.

Organisations can achieve collaboration among sub-units as also among member’s roles in a number of ways. OD techniques describe both structural as well as process-oriented interventions for collaboration.

Three of the most common methods for managing conflicts through encouraging collaboration are described below:

1. Creating Superordinate Goals:

Inter-group conflicts often develop because people get so involved in the achievement of their compartmentalized objectives, that they neglect the common goals for which they are working. These priorities, often perceived at the level of the group heads, also get pushed down the hierarchy, and become a major contributor to interdepartmental conflicts.

Many researchers suggest that a common understanding of shared goals can greatly facilitate a climate of collaboration. The current popularity of promoting a corporate vision (quality of product, customer service, increasing exports, etc.,) also highlights this process of creating superordinate goals, which help in unifying conflicting organisational energies. Research findings of Sherif and Sherif (1969) suggested that introduction of a “common enemy” helps in reducing hostility between groups.

Thus, when organizations face stiff competition in the market, it provides an opportunity of pitting the organisational team against market forces (it is interesting to note the extent to which the popular managerial terminology reflects this metaphor of battle, e.g., winning and losing, capturing the market, beating the competition, flagship company).

2. Joint Problem Solving:

This is one of the most frequently used techniques for increasing collaboration. It requires the conflicting parties to come together, analyse and define the problem, understand each other’s viewpoints, and arrive at a rational and objective solution through mutual interactions.

Intervention Format for Building Collaboration:

A number of formats have been described by management theorists and practitioners for effectively facilitating collaboration-building processes between conflicting groups. The underlying commonality among these interventions is in terms of the process, which they commonly follow.

The Typical Format for Conducting These Interventions:

1. Encourages conflicting parties to define and articulate their problems and perceptions separately;

2. Provides them opportunity for sharing these perceptions;

3. Once sharing is done, is to discuss and arrive at a common understanding of the problem;

4. Jointly explores alternatives for solving this problem, and arrives at a mutually acceptable solution;

5. Builds an action plan for implementation of this solution; and

6. Follows up and reviews the implementation at a future date.

The aim is to solve a problem, which is experienced by all parties, not to win or lose against each other. The usefulness of bringing people, face to face, lies in helping them to identify not only the differences, but also the similarities in their perceptions.

3. Increasing Interactions:

Often many interdepartmental conflicts are rooted in misperceptions and lack of understanding between different units. The functional segmentation is further augmented by each sub-unit developing its own norms of working and interacting. In the process of doing so, they also becomes insensitive to problems and requirements of other sub-units.

These demarcations can be broken down, if organisations provide more opportunities to the employees in these sub-Units to interact with each other. If people interact with each other, not only would they develop better understanding of each other’s way of functioning, but also may discover common interests, problems, and priorities.

For instance, the annual sales conferences, besides dealing with substantive organisational issues, also create a sense of camaraderie and understanding among executives looking after different territories. In many organizations, the same purposed achieved through more formalised means: they create a system of inter-unit, inter-divisional, and even inter-functional transfers (e.g., Hindustan Lever).

Inspite of the popularity of collaboration as a conflict management strategy (at least in the management literature), it is often not the most feasible one.

Derr (1978) pointed out that success of collaborative efforts depends on four basic preconditions:

(a) Conflicting units must be interdependent, i.e., should have long-term stakes in solving the problem;

(b) They must be equal in terms of their power in the organisation;

(c) There should be potential for mutual benefit as a result of solving the common problem; and,

(d) There should be organisational support (in terms of time, money and energy) available for the collaborative efforts.

It needs no great emphasis to point out that these conditions are not always present in the organisations. Sub-units lack power parity (in fact, that itself may – be the reason for conflict); for most departments, the stakes in solving a problem are short-term (meeting the annual targets); and only a few organisations are willing to invest resources in real team- building efforts (except as a cosmetic training programme). Most of the time, divisions and departments are left with no other alternative, than to adopt other strategies for managing conflicts.

It is also worth noting that the primary goal of any organisation is not achieving harmony and collaboration, but achievement of its strategic objectives. In many complex organisations, collaboration may not be a realistic, or even desirable, goal to strive for. Too much emphasis on collaboration (“we must live like a happy family”) can increase the chances of “group think”. Or, it can even become a tool in the hands of the political forces.

As Rico (1964) remarked:

The individuals or groups who are most vocal in advocating ‘harmony and happiness’ in an environment devoid of conflict, may only be protecting their vested interest in status quo.

B. Power-Play:

Power-play or power-politics is the archetypal antithesis of collaborative strategy. Whereas collaboration is a win/win strategy, which aims at establishing acceptable rules of interaction, power-play aims at a win/lose situation by circumventing or distorting the established rules. Derr (1978) defined power-play as “a secretive mode that could work in the best interest of those, whose covert objective is autonomy and whose desired impression is that of being committed.”

He also noted that this method of conflict management has often been condemned because it unleashes aggressive and hostile feelings, distorts or suppresses valid organisational information, displaces energies to unproductive purposes, and at times, even subverts organisational goals.

Nonetheless, power-play is an organisational reality, which often fulfills useful aims. There are a number of situations in which power-play and politicking may be an appropriate (or at least, an efficient) means of dealing with conflicts.

Some Such Situations Are:

1. When people need to work for their rational self-interest (which may not necessarily be contrary to organisational interests). For instance, experts in the organisation may like to maintain their autonomy, use their specialisation for organisational purposes, but without wanting to invest too much of their energies in building collaborative relations.

2. When the organisational environment is competitive, in which a collaborative stance may make one more vulnerable. For instance, if different divisions have to compete for budget allocation, then the sharing of critical information with others would make them aware of one’s weaknesses, and give them a strategic advantage.

3. When preconditions for collaboration are not met, but coexistence is necessary for achievement of personal goals. Such a situation would result in a sort of dynamic equilibrium between the conflicting parties. For instance, the relations between management and union often endeavour to maintain a balance between compatible self-interests (also note that inspite of their power-play, both often benefit. While the management is able to save through redeployment of labour, the workers manage to get better salaries or amenities).

4. When the dispute is ideological in nature. For instance, the conflicting parties may be unwilling to look at the dispute as a problem to be solved or negotiated over. The only course open in such a situation is to achieve one’s ends at the cost of others.

What behaviours constitute power-play? Often the political behaviours in organisations have been described as “games”, Mintzberg (1983a) listed out a number of political games, which are often played by people in the organisation with the intent of optimising their power. For instance, experts in the organisation may seek to safe-guard their power, by keeping their skills from becoming common to all, or privileged information may be used by a less powerful member to “blow the whistle” to an influential outsider on questionable/illegal behaviour by the organisation. Similarly, Wofford, Gerloff and Cummins (1977) identified a list of power tactics used by executives and sub-Limits in the organisations.

Let us look at some of the commonly used political behaviours:

1. Withholding Information:

This is the most common power tactic. Information is a source of power. If one retains control over this source, it would ensure others’ dependence, and give one an advantage. For instance, if the copies of personnel policies manual are not made available to all line managers, it leads to their dependence on the personnel department.

2. Blocking-off Incoming Information:

If one can manage to block or delay the information from reaching oneself, it not only allows one to avoid or delay making commitments, but also ensures that the other party is forced to make a “personal request”. Departments often build complicated (and vague) procedures, nurture inefficiencies, or create internal bottlenecks to ensure that they can seal off requests and demands from other departments. For instance, the stores section may develop a complex system for indenting spare parts (with the legitimate excuse of avoiding pilferage) to emphasise its power over the shop floor sections.

3. Delaying Agreements and Decisions:

The longer one can delay an agreement which would make one accountable, the greater maneuverability one would have. Often this tactics is used in the form of appointing a committee to look into the problem. The trick involved is in making a vague commitment (e.g., “we need to discuss it in detail”), which ostensibly indicates one’s sincerity, but in reality keeps the problem hanging.

4. Emphasising Perfectionism:

Being perfectionists, quality-conscious and uncompromising on solutions is a legitimate behaviour in most organizations. But it can also be used as a tool to obstruct the work processes of other organisations. It is often used both ways—one may demand perfectionism from others (e.g., the maintenance crew will not be released till the machine runs noiselessly), or one may practice perfectionism oneself (e.g., the finance department will not pass a bill till all related documents, even the trivial ones, are enclosed). In either case, it puts pressure on the other party.

5. Protecting one’s Territory.

Organizations are horizontally differentiated along functional specialities. The more one can maintain the uniqueness of one’s job activities, the greater would be one’s value. This is true of not only highly skilled specialists, but even of the unskilled job categories (e.g., the cleaning staff may get unionised and protest against their jobs being made a part of the helpers’ jobs on the shop-floor).

C. Bargaining:

Bargaining is a middle-ground between the collaborative and political strategies of conflict management. It incorporates elements from both strategies—the problem-solving stance of the collaborative approach, as well as the tactical moves and counter moves of the power-play. It is also one of the most commonly practised conflict management strategy.

Bacharach and Lawler (1981) Noted:

Bargaining is a central element in a mixed-motive setting. Given simultaneous incentives to cooperate and compete, mixed-motive relationships are inherently unstable and inevitably involve some distrust. In this context, bargaining is the primary means for keeping the conflict within acceptable bounds and avoiding a complete bifurcation of the relationship.

Bargaining, may not be the ideal approach, but it is definitely a practical one. It has its limitations: the win/lose stance can create new interpersonal or organisational conflicts; it can only help arriving at less than perfect compromise solution; and, it involves commitments which are more legal and formal than intrinsic in nature.

Inspite of these imperfections, it is useful in a number of ways:

1. It ensures that the conflicting parties openly share their concern for, and also arrive at, some immediate solution.

2. It provides an opportunity to the conflicting parties to interact with each other, implicitly or explicitly acknowledge mutual interdependence, and thus, build grounds for better understanding.

3. It is an efficient way of establishing power parity, paving way for future collaboration. Not only can the two parties recognise the value of what each can give or withhold, they also enlarge their areas of agreement by arriving at some common solution.

4. It is probably the most efficient way in which scarce resources can be distributed.

While bargaining is a rather complex and dynamic process, it does invite certain predictable forms of behaviour from the involved parties.

Based on studies on bargaining behaviour, one can identify the following four critical features of this approach:

1. Selective Sharing of Information:

In the bargaining process, parties use information selectively and strategically. While much information may eventually be exchanged by the parties during the process, this sharing is done in stages, to enable one to maintain some strategic advantage. On certain issues, complete information may not even be shared altogether. For instance, the Management may reveal its budget for welfare activities only after it has gauged the nature of demands the union is likely to insist upon.

2. Continuous Revaluation of one’s Position:

Since the picture of the problem as construed/ presented by the other, emerges gradually during the process, it becomes necessary for each party to re-evaluate their position during the process. This is often because each may realise that their insistence on some preferred alternative can have undesirable consequences for some other important concerns. For instance, the marketing wing may stop insisting on a new product-line, when it realises that this may affect its other important orders.

3. Variations in Pressure Tactics:

Corresponding to revaluation of one’s position, the process is characterised by what Thomas (1976) described as the “escalation/de-escalation” dynamics. Thus, during the bargaining process, the conflicting parties may increase or decrease the amount of pressure during various phases. For instance, one may increase or decrease the number of disputed issues, adopt flexibility on extreme demands, switch from an environment of agreement to that of hostility, and so on.

4. Trade-Offs:

The solutions in bargaining are achieved through periodic trade-offs during the bargaining process. Each party successively gives some concessions to the other, la exchange to certain hems of perceived importance. The net result is that most of the solutions arrived through bargaining are compromise solutions,

D. Structural and Procedural Strategies:

Organisational conflicts, often originate from the specific organisational conditions. It would be a reasonable contention, that manipulation of organisational elements would also help in resolving these conflicts. In fact, one of the purposes of coordinate and integrating mechanisms is basically to ensure avoidance of conflicts among the various sub-units. We will discuss some of the conflict management strategies, which involve rearrangement of organisational elements.

1. Reducing Interdependence Among Units:

Since one of the main reasons for conflicts to occur is the interdependence of the sub-units, to reduce the conflicts these sub-units could be made more autonomous and independent. For instance, if one unit is dependent on the outputs of another the conflict can be reduced by creating a buffer stock in the first unit. Alternatively, the first unit may be given freedom to obtain is inputs from other sources. Organisations, when they rearrange themselves by creating profit centres, also reduce the interdependence among the sub-units.

2. Top-Down Interventions:

If two parties fail to resolve their disagreements, it can be handled at the level of the mutual superior. The superior, in this case, takes up the role of an arbitrator and integrator. In certain cases, this role can also be played by a formal organisational system. For instance, the grievance redressal system in an organisation often helps in resolving conflicts which cannot be ordinarily resolved by one parties involved.

3. Enlarging Resources:

Since conflicts often arise because of scarce resources, expanding the resource base can be a successful strategy for eliminating conflicts. This, however, is easier said than done. Organisations work on the principle of optimising output even with limited resources, and increasing resources would definitely involve greater investments, which the organisation may not be willing to make.

The ultimate decision would depend upon considerations such as the relative costs of resources and the adverse impact of conflicts. Even within these limitations, however, it is often possible for the organisations to increase their resource utilisation. Manpower, equipments, and other resources can often be creatively and flexibly redeployed to overcome periods of scarcity.

4. Combining Conflicting Units:

This strategy is sometimes used in the organisations by restructuring the conflicting units in a manner so that one incorporates the other. For instance, in many manufacturing companies the quality control function is a part of the production department. It ensures that conflict between the two functions can be resolved at a local level. Similarly, in one of the academic institutes, the conflict between the Personnel and IR Department and Organisational Behaviour Department arose due to the overlapping nature of these disciplines. The strategy used was to combine the two and form a new department of HRD,

Implications for Managers:

A focus on the role of power in organisations is important for one to understand and to cope with the reality of organizational life.

For the practicing managers, the preceding discussion offers numerous insights for effective functioning:

1. It is important to recognise that organisations are not merely rational entities, designed by tangible situational contingencies. Rather, many intangible human and structural factors also conspire to create what an organization would ultimately be. In fact, as we saw, many rationally structured activities also carry an underlying implication for power distribution and sharing among the members. An awareness of these implications is essential for managers to function effectively.

2. Ideologically, a collaborative stance is necessary for the organizations to become more humane systems to work in. It is equally important, however, to recognise that collaboration may not always be a successful strategy to deal with the conflicts and power-issues. The ability and skills for using other strategies for conflict-resolutions (i.e., bargaining and power-play) are perhaps equally important for managers to be effective in achieving results.

3. Lastly, a fuller appreciation of the role of power in organisations would be incomplete, without focusing on how it influences the decision-making and leadership processes in the organization.