Agro-industries in India rank fifth in the industrial economy in terms of their contribution to value addition. This sector contributed 13.5 per cent (1997) of the total industrial output with a direct employment generation for more than 15 lakh persons and this was 19 per cent of the labour force in industries.

With capital being only 5.2 per cent of the industrial investment, the employment generation is 3.66 times the employment generation in non-food industries.

The following are top 10 food group industries:

1. Food grains processing and milling.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Dairy products e.g., milk in all forms and allied dairy products like curd, whey, butter milk, ghee, lassi, paneer, flavoured and chilled milk, shreekhand etc.

3. Alcoholic drinks.

4. Non-alcoholic drinks.

5. Processed, tinned and other packaged vegetables.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

6. Products made from fruits.

7. Cooked vegetables ready to be used after dipping the package in the boiling water for 2 minutes.

8. Confectionery items of exotic types.

9. Flour-based products from bread to biscuits or packaged ready to use material for so many common dishes like custard, dosa mix, idli mix, gulab jamun mix to – number of items.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

10. Products based on animal products, including medicines.

Defence services, police services, institutional buyers buy 60 per cent of the packaged food; the households pick up just 5 per cent. The institutional sector comprises of hotels, restaurants, hostels, airlines, railways. Nearly 35 per cent of such products are exported.

Oligopoly prices are charged from the household consumers and if the demand becomes sluggish, the producers do not reduce the price but attach some “freebees”.

Prices of frozen products become almost 2 times; of canned and bottled products 3 to 6 times; of pickled items become 6 times and of dehydrated items become 6 to 10 times. As new crops of vegetables and fruits come, the prices are high.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

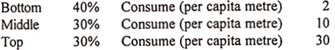

When the market arrivals reach peak levels, the prices are mostly down to one-sixth to one-tenth level. The rich enter their market first and other groups join with a time lag when they can afford prices. The poor purchase them when the prices become the lowest. They can wait.

The costs of raw materials are usually 30 per cent in most of the agro-products; use of utilities like power add up 10 per cent; transportation adds another 10 per cent; packaging costs are as high as 30 per cent The rest of 20 per cent costs go towards storage, margins of producers/middlemen and retailing. Now-a-days metal cans, glass containers, plastic containers/bags and aseptic bags are common for packaging.

Many agro-industries are no industries in the sense of factories. (Hence we can coin the word “manufacturing sector” for factory segment and manufacturing for all. The word “industry” is infact used for all activities including agriculture.

We say “national income by industrial origin, whereby industry means “labour” – work or hard work.) Unorganised sector dominates in number. There are innumerable bakeries, spice processing units, pickles units, flour mills, daal mills, oil ghanies etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the food industry fresh food industry dominates. It accounts of 93 per cent of the volume and 74 per cent of the food market. Semi-processed food constitutes 5 per cent of volume with a share of 16 per cent of value. Processed food has a share only 2 per cent in volume and 10 per cent in value, making it the most under-exploited sector of the food industry due to its being 3 to 5 times dearer.

By 2000, there were around 5000 licensed units engaged in the processing of vegetables and fruits; 90 per cent of them in the SSI and cottage industries sectors and 10 per cent in the medium and large sectors. These units mostly use traditional methods of processing and preservation like manual preparation, air/sun drying, batch pan concentration etc.

However, recently the state of the art technologies like vacuum concentration, aseptic packaging, freeze drying and individual quick freezing have been adopted. There are automatic and semi-automatic plants for the same.

Installed capacities are difficult to assess because of the seasonalities and different types of machines. On the basis of the figures given by the Ministry of Food Processing Industries, the installed capacity increased to nearly three times to be around 21 lakh tonnes by the year 2002-03. This was three times as much about 13 years back. Production too was four times as much at around 10- 12 lakh tonnes.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Not more than 5 to 6 per cent of the fruits and vegetables are processed in India. In countries like Malaysia, the USA, Brazil and Israel, nearly two-third to three-fourth output is processed.

Jams, jellies, dehydrated vegetables, marmalades, beverages, squashes, syrups, fruit juices fresh or put in paper-made packaging, fruits pulps, cooked vegetables (which can be made ready-to-serve with two-minutes boiling), canned fruits and vegetables with preservatives, bottled fruits and vegetables, fruit juice concentrates, pickles and chutneys, spice-packages for different types of dishes, tomato products, ketchups and sauces, frozen fruits and vegetables, candied or crystalized fruits, vinegar etc. are important food processing industries.

The top four are:

(i) Fruit pulp (25%),

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Beverages (25%),

(iii) Pickles and chutneys, and

(iv) Frozen fruits and vegetables about 12.5% each.

Ministry of Food Processing Industries (Est. 1998) tries to improve production and exports profiles. There is then APEDA (The Agricultural and Processed Food Products Exports Development Authority) which claims all facilities can be given. Provisions exist right from 1950s about the quality control.

In recent years excise duties are being slashed. There is that general reduction in the credit lending rates of which advantage can be taken by the growers.

Reservations and continued reservations are reviewed so that whatever is necessary can be arranged. EXIM policies of all years contain the necessary props for the agro-industries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is estimated that by 2005, the food industry will grow to be of the size of Rs. 4, 80,000 crore. It is to be noted that some industries of food-processing are giving rise to those products which the dieticians call “junk food”. Their consumption is leading to over-weight of children and the adults.

They are making consumers unbelievably fat. The bad cholesterol levels are rising. Their consumers are becoming prone to diabetes, high blood pressure, heart diseases and all attendant problems.

Tobacco products and alcohol leads towards such ailments of liver, kidney etc. that ultimately there is multiple organs failure. Confectionery items, pizza, pasta, noodles, buns, burgers, ice-creams, soft drinks etc. if taken in excessive way may lead to all such things.

It is to be noted that while the increase in consumption pattern by 2005 for such items as rice, wheat and pulses will be just 14 per cent it is targeted to be 150 per cent for snack products, ice cream and “eating-out” products. For products which do not fall in the harmful class but come in the semi-necessity class (like soft drinks, packaged atta, meat preparations), the demand is expected to increase to be double i.e., 100 per cent increase.

Indian laws do not permit the corporate ownership of land for growing raw material for the use in the agro-industries, except in tea, coffee, rubber and in some cases sugarcane. Hence the companies have to outsource the raw materials. They maintain a close contact with the progressive farmers to grow the required things with specified technology of genetically muted seeds grown with the required inputs as desired by them.

There are land based cold storages as well as moving (trucks) cold storage facilities but they are totally inadequate in that 30 per cent of production still rots and cannot be used either for ‘table consumption’ or as ‘processed item of consumption’. Reefer trains of containers for fruits and vegetables can be counted on finger and they run on selected routes (say Delhi-Mumbai).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Punjab, Haryana and Delhi have better cold storage facilities than other States. Figures are available for 1995-96 and they show that the sales of food processing industries were of Rs. 3782 crore; operating profits were Rs. 418 crore; gross profits Rs. 332 crores and net profits Rs. 208 crores.

The new rich class which includes many scamsters is patronizing all things costly from cars to farm houses or from palatial city houses to foreign visits. One reason why the market of such ordinary things as of processed food items cannot be patronized by a vested majority is the fact that post-LPG (liberalisation, privatization, globalisation), the distribution of employment and income earning opportunities is becoming ever more skewed.

The relative incomes of the middle class, lower middle class and lower classes are falling sharply but of the upper class are rising sharply and steeply. Sky seems to be the limit of their capabilities of earning. Since the income elasticity of demand for agro-products is very very low at this stage, the agro-products is very low at this stage, the agro-products and agro-processing industries are yet not able to ensure that very little of the production of vegetables and fruits is wasted.

Tragi-Comic Aspects of Participation of MNCs in the Agro-Industries in India:

The good aspect is that the foreign companies (MNCs) bring technology. Indian firms could not invent the technology of potato chips as they are marketed by the foreign firms. Then these firms bring capital and then take initiative to pickup big farmers of progressive pockets of various States to produce the raw materials of the required quality.

The tragic aspect is that instead of permitting this Indian industrialist should have taken the lead to pay the royalty for technology (if the technology could not be developed by them) and then do all other works themselves. Very few Indian firms enjoy the goodwill that their quality will be respected.

Suggestions on Manufacturing for Agro-Industries:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Some important lines of manufacture can be studied:

1. Grain Processing:

They are rice mills, wheat flour mills and daal mills. India is the second largest producer of rice and fourth largest producer of wheat in the world. There are nearly 1.5 lakh rice mills. The estimates about others (rounded off) can be about 95000 hullers, 5000 shellers, 10000 huller cum shellers and nearly 40000 modern rice mills.

Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Chhattisgarh are the most important four States for rice mills. Rice gets its name but except for basmati all other types of rice are sold loose bearing grade name rather than brand name (kalimooch, dubraj, bhunjia).

There are close to 850 wheat roller flour mills. These mills exist in all the States, more so in the wheat belts. However, there are many flour mills in Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Bihar.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Officially India is in “Operation Flood” (milk production revolution)—III. About 55 per cent of the milk produced in India is converted to milk products- organised sector having 10 per cent share and the unorganised sector 90 per cent.

Curd, sweet curd, shreekhand, whey, butter milk, salted-spiced butter milk, sweet milk, condensed milk, lassi, butter, paneer (cheese), ghee, ice-cream, milk powder, whole milk, toned milk, milk without fat, malted milk, infant baby foods, skimmed milk, dairy whiteners are agro-processed products.

3. Consumer Food Industries:

They are innumerable. There are industries which produce poha, salted grams, fried namkeens of all sorts, boondies, ‘sev’ with different admixtures of spices and of various shapes and thickness (like ganthias are without spices), roasted and pressed chana zor garam, chips of bananas or potatoes, nuts salted and unsalted, dried fruits of several types, pizzas, bread, buns, “paav”, biscuits, biscuits with cream (actually hydrogenated oil laced with crystal sugar), badees of various types of daals including of soyabean, ready to use powders for idli, dosa, gulab jamun, tarts, pies, pellets of many things, “maggy type products “, sivai, coco-toffees, toffees and chocolates of hundreds of types, and fruit juices of several types.

4. Cotton Textile Industry:

If all types of producing units, from handlooms to most modern mills, are included they would account for the employment of nearly 2 crore persons directly and all types of clothes (included blended) account for 20 per cent of the industrial output. However exports have a higher percentage in the total i.e., one-third (33%) of all the exports earnings.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These exports are not merely of cotton cloths and clothes but mixed also. Readymade garments are both imported and exported. India scores over other countries because of the cheapness. Chinese have their own system of costing. (Chinese say that since land is a free gift of Nature, minerals and a good part of the produce of earth can be regarded as costless. Hence the world finds it difficult to charge them with dumping).

Whichever middle-east country is exporting, they have atleast two things that Indians do not have. First, their clothes have better shine, sheen, finis, finesse and finish. They colours and designs are simply exotic. Secondly, their supplies are exactly what their samples were on which count Indians fail. Their time saving is such that if a ship takes 7 days to reach destination, the work of (say) putting buttons in the holes, pressing the clothes and packaging can be done on the ship itself.

The decentralised sector is gaining over the mill sector. In most countries this is other way round. In the year 1950-51, the mill sector produced 3780 m.sq. metres of clothes while the production of the decentralized sector was 1010 m.sq. metres. The percentage shares were 79:21 respectively. However, by 1997-98 these shares were 5 per cent versus 95 per cent respectively.

Powerloom and handloom sectors lead the mill sector in all types of clothes, cotton and blended in different proportions. Rural consumption pattern of cloth is highly skewed which proves the point the skewness in income is the most important problem of rural marketing rather than a question of marketing strategy.

The poor also prefer blended clothes because they last longer, though there is a lot of cheating on the part of the producers who produce cloths/clothes which are very substandard, bad for skin and give too much of “electric-like charge ” (at night if one is moving on a scooter, the clothes give “sparks ” without involving fire and if one alights from the vehicle and touches iron, once again a sort of “current shock” is there). It is also seen that some clothes do not last even a few days while good ones seem never to wear off.

Per capita availability of clothes is now 32 metres as against half 40 years ago. It was almost 50:50 for cotton and non-cotton clothes. The increase in the man-made fibre was 1500 per cent but in case of the cotton cloth it was mere 14 per cent in all these 40 years ending 2002. Exports were over Rs. 50000 crore and they were 760 times!

Most of mills were old. The mill-owners wanted to use the mill land for urban uses and would have earned billions of rupees with which they could buy most modern industrial machinery and could have established mill complexes outside Mumbai or Surat or Ahmedabad. The Government wanted the land to be surrendered to them. The mill-owners preferred to close down the mills and not use the land for any purpose. Better senses are prevailing now on the government.

Government had imposed high duties; had put restrictions on the import of machinery and good cotton and were non-cooperative in most other ways. The mill owners, on the other hand, were always anti-labour and they continue to be. Lay off was their chief weapon for starving out the workers.

The trade union leaders too were professional agitators and did nothing to improve productivity. There were controls of various types so that the government officials and HPPs could make money. Despite all odds the industry continued its upward movement but lagged behind China, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Singapore etc. in respect of all performance ratios.

Old machinery is being mentioned as a problem for the last 50 years! There were mills which installed new technology machines but the old machines could not be replaced with the new everywhere. That was due to faulty land-utilisation policy.

Glut in the cloth market, semi-nakedness of the people, thriving market of the old and discarded garments, clearance sale here and there and everywhere at all times, and closure of one or two shifts in mills are common but contradictory features.

Only a few venturesome companies suddenly appear in the market with publicity blitz, offering several cars, gold ornaments and whatnots in prizes and then disappearing with scams. They remain there; they just change the brand names of their cloths. Such unhealthy practices also abound.

IDBI which tried to help textile industry reportedly failed” as corporation. Low price of cotton was an advantage but poor quality was a problem. Low wage structure is an advantage but low productivity is a problem. Long history of textiles is an advantage but sub-par management from international norms is a problem. Concessions to the industry are gains to the industry but industrialists thrive on them.

We will not consider production in the unorganised sector as a “problem “. It is a boon. It is providing employment to millions and the traditional arts of India are kept alive. The mills are themselves to be blamed for their ills. It was a nothing short of a self-inflicted tragedy when the management of the sick mills was given by National Textile Corporation or by the State Textile Corporation to the bureaucrats.

They administered and did not manage; and the employees were a law unto themselves when work-shirking and low productivity were their norms in the face of assured employment. There was never a meeting of minds on a cooperative basis that could save the mills. Everyone was taking a piece from crumbling ancient fort for personal keepsake, so it can be said.

The 1985 “Textile Policy” of the Government of India covered all aspects from blending of the fibre, from stage of production approach (cotton growing, ginning, making yarns, spinning, weaving with exotic designs, processing, packaging and marketing), yet those who were in charge of implementing the policy could not match the new international norms and standards.

When the “New Textile Policy of 1985” could not bring the desired results another “new” policy was announced in the year 2000. There had to be one fitting the new century. The target of exports was revised upwards to 5 times to be of the order of $ 50 billion — half readymade and half non-readymade. Reservations to SSI were removed and the foreign investors were permitted to take over the name given was 100 per cent FDI was permitted.

Then only the leading countries agreed to lift QRs (quantitative restrictions) on the exports from India. Reservations for handlooms continue. One big problem with handlooms and powerlooms had been shortage of power. Cheap credit does not help if the quality of cotton is not good (Rs. 11000 crore plan is there for that, though even by the fall of 2003 the problems of cotton growers were not solved).

Permission to export cotton yarn was pointed out as the policy according to LPG but the crores of persons employed in this industry want that government should have assisted the domestic producers in providing level playing fields to compete with the foreigners.

Employment interests of the retrenched workers of the sick textile mills could have been addressed if only power could be provided on steady and cheap basis to the powerloom operators. Government functionaries, it is alleged, do not assist the weavers in improving quality but in exercising controls over them. The targets of exports of $ 50 billion by 2010 from these activities require better policies on field rather than on paper.

Non-viable units are to be closed and the land used for any other purpose, including establishment of the most modern textile mills, if the promoters want and can afford. If the sick units get eliminated the surviving efficient units can face international competition. There will of course be problems of finding employment for the workers but they have either to seek employment in new mills, or operate powerlooms or seek job elsewhere or live on the past earnings, if old.

If handlooms and powerlooms are not helped and they do not become efficient it will be the second death of Gandhiji. After all spinning yarn for one’s own cloth and weaving clothes on decentralised basis was one of the Gandhian strategies of tackling rural unemployment.

Started in 1885, this industry was left with 69 working units by 2002. Nearly half a crore persons are employed in the cultivation activities directly and indirectly and 2.5 lakhs in the mills despite closure of some units and rationalisation.

Jute industry of India passed through a grave crisis immediately after Independence. Almost 99 per cent mills were in India and almost 90 per cent of the jute growing area went to East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. Pakistan started charging high prices and when in 1949 the Pound Sterling was devalued vis-a-vis dollar/gold, all Commonwealth countries, except Pakistan devalued by the same percentage.

That made jute exports from the then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) even costlier. India had to grow jute in rice growing area and import rice from outside. India soon became self-sufficient but the golden fibre of the then East Pakistan was allowed to rot. This sowed seeds of discontent against the West Pakistanies in East Pakistan who were in any case using the foreign exchange earned from the eastern wing for the benefit of the western wing only – or almost.

When they forced East Pakistanies to abandon their language and when they denied the right to rule Pakistan even when in majority after elections, freedom struggle was started and India had to intervene to liberate Bangladesh and send back over a crore Bangladeshies who had to be sheltered in India.

Yield per hectare also improved from nearly 1000 kg per hectare to a little over 2000 per hectare and this too helped India. However, now India’s near monopoly position is eroded to one-third of the world production. Other important countries are Bangladesh, Thailand and Brazil.

The real achievement of jute industry is not modernisation but finding out versatile uses of jute. It can be used to look like wool, silk and other types of yarn and now hundreds of items are being manufactured rather than mere gunny bags. Production of jute textiles was twice at high at the peak level in recent years than at the time of Independence (1800 versus 900 thousand tonnes). Exports were, however, down from nearly 8 lakh tonnes to nearly 2.5 to 3 lakh tonnes and that was the reason why domestic use had to be increased.

That increased thanks to industrialisation. Domestic consumption was up by 14to 15 times. (18 lakh or 17 lakh minus 2.5 to 3 lakh tonnes). Synthetic packaging material including laminated bags are weather proof and leak proof and they are cheaper also. Jute goods are bio-degradable but the substitutes are environmental hazards and menace. Jute industry is going on despite odds from international competition, competition from substitutes and sub-optimal operational efficiency.

Village Industries:

Mahatama Gandhi did not want “rural industrialisation “; he wanted “realisation of industries “. Ruralisation of industries means that the industries take their inputs from the rural areas, employ rural people and their outputs first meet the needs/demand of the rural people. Thereafter and simultaneously but as of secondary importance they can be like other industries.

Modifying another saying we can write that ruralisation of industries will be ensured when the “production is by the rural people, near the rural people and for the rural people primarily.”

There is “tiny industrial sector” in rural areas which is of small artisanship ventures. Then come small scale industries which are generally food processing industries.

It is to be noted that even in the heydays of “planned economic development in India”, the per capita public expenditure on tiny sector was just 0.80 rupee per capita; or, put it in another way, it was Rs. 137 per square kilometres. During the 1980s it “rose” to Rs. 2.2 per person (rural areas) and Rs. 480 per square kilometres.

Even then in mid-1980s these tiny ventures and village industries were employing 1.33 crore persons with an output of Rs. 4422 crore.

The share of non-factory, non-household small scale industries was 65 per cent during the decade of 1980s and of the factory sector 35 per cent. The big public sector units had assured market in all government investment schemes. However, now under GATT-VIII and WTO provisions, competition from the private national and international business is there. Nothing can be taken for granted.

Many SSI units are closing down as their costs were high and quality low in the assured market. There were reservations in favour of the SSI. Wage-employment positions were good. Now wage-employment positions in agro-industries are not threatened. Of the rural industries, food product industries, beverage industries, activities based on tobacco, leather showed improvement.

According to the Economic Survey of the Government of India (2002-03), on March, 2001, there were 2.53 lakh units in the SSI sector and 3317 units in non-SSI sector that were sick. Nearly Rs. 26000 crore of the bank credit was locked in them. We cannot say for sure how many of these units were born sick, how many became sick and on how many the sickness was thrust upon. It is very good business in India to borrow from the banks and not return and fake sickness.

Village and cottage industries all belong to rural economy. However, some tiny units can be in urban areas also rather in rural and semi-rural areas only. SSI units to have their linkages with the rural economies. Mineral based, agro-raw-material-based, forest-based industries have their linkages with the rural economies.

Most of the industrial workers can trace their roots to the rural areas. Usually the rural people come to urban areas to get education, technical education, work experience and then graduate to industrial units of various sorts in stages or directly.

Hence factor relations, input-output as well as output-input relations, wage-employment relations, income-expenditure relations are all there between rural and urban activities and people.

In the year 2002-03 there were 28.5 lakh registered SSI units and 7.23 unregistered SSI units. Their production was estimated to be of 7.4 lakh-crore rupees at current prices. They provided employment to nearly 2 crore persons. Exports from these industries were of nearly Rs. 70000 crore.

Some Examples of Prime Moving Activities:

Every 10 crore cattle of India can produce 30 crore tonnes of dung and 7000 crore cubic metres of gas (through the gobar gas plants). This can lead to saving of 15 crores tonnes of firewood and lakhs of trees.

Considering a village of 500 persons, 250 cattle head and 100 houses, it can be ensured that despite a 75 per cent dung collection efficiency, a low bio-gas yield will provide a total energy of about 667.5 kWh per day at a generation cost of around 25 paise per kWh. (Year 2000 prices).

At present the villagers do not pay electricity bills of the State Electricity Boards and the Electricity Boards cannot maintain the transmission system. There is now a vicious circle. To keep the State Electricity Boards running, the EBs are now using such meters that run fast. If a person is not politically well connected or connected with the HPPs (high powered persons) he pays hell lot more charges than he uses electricity.

This is a general complaint cutting across the boundary lines of States and political leanings of the populace. The establishment of such rural electricity gobar gas plus bio-litter power plants plus solar energy cooking units can reduce the load on the SEBs and the villages themselves.

There is urgent need that private business entities of the rural areas themselves (the old mahajans and merchants) be co-opted for this. They are there and can take up the jobs. An outside economic entity will be able to take up the work only when it is viable on a larger scale. Direct and indirect and linkage effects will be very many. Each village (of the above size) could get nearly 300 tonnes of organic manures; 4.5 tonnes of nitrogen; 22 tonnes of additional foodgrains or raw materials – all on the basis of methane gas digester based on dung of 250 animals.

The energy generated will sufficient for 10 pump sets (200 kWh) cooking (200 kWh) and the rest 267.5 kWh per day for 5 rural industries.

The inaction on this front is simply beyond comprehension. Madhya Pradesh Government’s record, for example- is that it could not distribute even 300 solar cookers a year during all the years the Department of Non-Conventional Energy is operational.

Methane gas digesters, based on cattle dung and other organic matter can decay, can give methane gas and they can be of continuous load or batch load. First, the aerobic bacteria and then anaerobic bacteria do the job. It will then be necessary that the processes during which these bacteria do their work should be monitored.

This is the crux of the operation of these methane gas digesters. This balance needs regular feed of the right materials with enough liquid, proper maintenance of alkali-acid balance, the right temperature of biological survival of bacteria and adequate quantity of raw material for digestion.

For example in the certain states (as in Madhya Pradesh) mini- cement plants can be established. In certain regions only cement stones are found as in the Katni-Rewa-Shahdol belt. Many districts in Andhra Pradesh would find to use granite wastes for laying roads and pathways because they are cheaper. Similarly in many parts of Rajasthan waste pieces of marble stones can be used for similar purposes. It will be costlier to bring Iess costly stones from elsewhere!

Vertical kilns of 500 tonnes capacity a year can be built. They may not be economical in operation but prove economical when economies in transport costs are taken into account. The benefits of employment are additional. The cement may be of low quality but will be good enough for many rural works that do not require standard cement and these housing, step bunds, stop bunds of small sizes, paving of rural pathways.

Chinese experience in this regard was once published in Yojna, reference lost. As the workability, strength, durability and impermeability and density in the mortar concrete made with cement will differ, different uses for such a mixture can be found. The quality of adhesiveness materials depends on the chemical properties, soundness of materials, setting, time tensile strength and such characteristics and they change the adhesiveness, can be made to differ for different works.

It is the efficiency of the firing only which is important. Stone crushing, conveying broken pieces to the homogenizer, grinding clinkers, packaging and transportation can be of any type. The main problem is to fire the homogenized calcareous and argillaceous clay, laterite, sand bauxite, coal and coke breeze and some other substance with basic substance limestone or slag to attain efficiency.

We can always find some experts to make a village just one village implement these schemes. Only some well-known persons like Rajendera Singh of water harvesting fame of Rajashthan, Anna Hazare of Maharashtra and Magsaysay award winning institutions can be co-opted for guidance and transparency.

Small Scale Industries (SSI) may be mostly located in rural areas or what were once rural areas but became “industrial estates “. They may or may not be based on rural input mostly taken from agriculture and allied activities but also from forests and minor minerals.

SSI is supposed to provide some benefits in the form of employment or taking inputs from rural areas or supplying outputs to rural people to be used as inputs of development or to be used as consumption goods.

It is also true that the SSI units in rural areas may not provide any of the above benefits. There are many Hundred Percent Export Oriented Industries (HPEOIs) that use nothing from the rural areas and give nothing to the rural areas. There are in the rural areas to take advantage of free or almost free land, water and other facilities. City people are employed and they commute to these factories.

SSI units currently produce outputs of nearly 6 lakh-crore rupees; give employment to nearly 1.8 crore persons directly and export almost one-twelvth of their total production.

Villages mostly send their village craft goods to the villagers or to the people of nearly towns. If they want to go “national or international” they will have to take the help of the middlemen and governments can be such middlemen. If private middlemen are considered “exploitative”, the governmental middlemen impose a “high cost burden”.

Unless the marketing is done through honest and efficient cooperatives of the villagers, fair deal to the rural people is scarcely possible. Credit support is available not on the viability of the purpose rather than on the viability of the person.

So far government has not been upto the mark in providing electricity, guild- type sheds with all facilities, research advantage and the most needed patent advantage in international market for hundreds of the items produced in rural areas. Handloom, powerloom and village craft artisans are in bad shape so much so that no year has gone by since Independence when some of them do not commit suicide.

Each naib-tehsil (sub-taluka) should have a guild; or if that is not possible at least each block headquarter should have one totally based on the local raw materials. Resource inventories can be prepared; gap between human resource potentials and the present use can be found; then prime-moving activities that are agri-business and agro- industry based can be identified for the region, and then physical and financial inputs arranged according to a time profile.

Precise figures are not available but on the basis of the guesstimates published in the past and the trend rates, it can be said that as India entered 21st century the value of outputs handicraft and agro-based industries must have crossed Rs. 1 lakh crore marks.

Certain lines of rural products can command high demand in urban areas. It is generally seen that many people buy atleast a few dresses of rural type for their urban children e.g., Lambaadi dresses with their trinkets etc., or Rajasthani chunri dresses etc. These things can be produced for urban centres also.

Jobs should be taken to rural areas rather than rural people forced to seek jobs in urban areas Metropolitan sanitation has deteriorated beyond repair in all major cities be they Delhi, Chennai, Mumbai, or Kolkata or Kanpur or Indore. The urban slums are graves of over-migration of the rural people. Hence rural industrialisation and ruralisation of industries assume importance.

Long reference lists increase the costs of publications. The information in this article is based upon hundreds of papers that have appeared in the EP W, Yojna, Khadi and Gramudyog journal, AlCC Economic Review (in the past), Eastern Economist (now no longer in publication, HSoA, HSO Environment, Economic Survey Gol, and weekly, fortnightly or monthly, quarterly bulletins of certain banks. ADB (Asian Development Bank) and World Bank have published quite a few monographs on rural enterprises.

It is agri-business that should increase first or there should be planning for its development. Then agri-industries and agro- industries can develop.

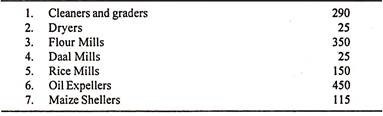

In the year 2000, the estimated productions of some important lines of product were: