There are three broad exchange rate systems—currency board, fixed exchange rate and floating rate exchange rate. A fourth can be added when a country does not have its own currency and merely adopts another country’s currency. The fixed exchange rate has three variants and the floating exchange rate has two variants.

1. Fixed (or Pegged) Exchange Rate:

This consists of – (i) rigid peg with a horizontal band, (ii) crawling peg and (iii) crawling band.

Variants of a Fixed Exchange Rate System:

1. Rigid Peg with a Horizontal Band:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is an exchange rate system under which the exchange rate fluctuation is maintained by the central bank within a range that may be specified (Iceland) or not specified (Croatia). The specified band may be one-sided (+7% in Vietnam), a narrow range (+ 2.25% in Denmark) or a broad range (+ 77.5% in Libya).

2. Crawling Peg:

The par value of the domestic currency is set with reference to a selected foreign currency (or precious metal or currency basket) and is reset at intervals, according to pre-set criteria such as change in inflation rate. The central bank decides the new par value based on the average exchange rate over the previous few weeks or months in the foreign exchange market. The biggest advantage of the crawling peg is its responsiveness to the market value of the domestic currency.

3. Crawling Band:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The domestic currency is on a crawling peg which is maintained within a range (band).

2. Floating Exchange Rate:

This consists of – (i) managed float and (ii) free float.

When a country has its own currency as legal tender, it can choose between the three broad types of exchange rate systems. Within the fixed exchange rate, a country can choose a rigid peg or a crawling peg. Again within each peg, it can choose to have a horizontal band within which its exchange rate would be permitted to fluctuate. Within the floating exchange rate system, a country can choose a free float or a managed float. The main source of the exchange rate system followed by any country is the IMF’s Annual Report on exchange rate arrangements.

Many countries declare that they follow a particular exchange rate system, but may follow another system in practice:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. Exchange Arrangements with No Separate Legal Tender:

A few countries (such as Micronesia and San Marino) select another country’s currency as legal tender. This is called Dollarization, since the selected foreign currency is usually the US dollar.

ii. Currency Board:

The central bank of the country promises to convert domestic currency (on demand and at any point in time) for a predetermined number of units of a specific foreign currency. In order to fulfill this promise, the central bank has to hold foreign exchange reserves in the selected foreign currency. Usually a government decides to adopt a currency board when the holders of domestic currency lose confidence in it is as a medium of exchange, triggered by rampant inflation, unbridled government debt (resulting in fiscal deficits) and recession. A currency board is expected to restore faith in the domestic currency.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The first currency board was set up in Mauritius in 1849. Hong Kong has had a currency board since 1983 when its currency was linked to the US dollar. Argentina chose the currency board in 1991 and Bosnia in 1997. Argentina’s currency board promised to convert each peso into one US dollar. The Central Bank held only 66% of the peso as dollar reserves, when it should have held 100% (given the 1:1 peso/dollar currency board arrangement). In 2001, Argentina defaulted in repayment of its external debt and confidence in the Argentine peso plunged. There was a run on the banking system, and the government abandoned the currency board.

iii. Fixed Exchange Rate:

It is also called the pegged exchange rate. The par value of the domestic currency is set with reference to a selected foreign currency (or precious metal or currency basket). The exchange rate fluctuates with a range (usually +1% of the par value).

The domestic currency’s par value is fixed by the monetary authorities against any of the following:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

a. A precious metal (gold in the gold standard)

b. A single currency, which can be an artificial currency (such as the SDR), or an existing currency (such as the US dollar or the pound sterling). When a single currency is chosen, in some cases colonial legacy determines the choice—most former French colonies chose the French franc, while former British colonies tended to choose the pound sterling. Sometimes, a fixed exchange rate is adapted to arrest the steep fall in value of the domestic currency. In September 1998, the Malaysian monetary authorities announced a rigid peg of 3.8 ringgit/USD after the Ringgit plunged by 60% against the US dollar.

c. A currency basket as in the case of the Indian rupee in 1975; the Indian rupee was de-linked from the pound and linked to a basket of currencies. The central bank may keep the currencies in the basket a secret, or make the currency In 2005, China pegged its yuan to a currency basket whose composition and weights are undisclosed.

Variants of a Floating Exchange Rate System:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Managed Float:

A floating exchange rate (or flexible exchange rate) is the opposite of the fixed exchange rate. Market forces determine the value of the domestic currency against a selected foreign currency. A managed float (or dirty float) is a floating exchange rate in which the monetary authorities influence the exchange rate (through direct or indirect intervention without specifying the target exchange rate. India is on a managed float.

2. Free Float or Clean Float:

Here, the exchange rate is purely determined by market forces (demand and supply of the currency).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

De Facto and De Jure Exchange Rate Systems:

A de facto exchange rate is the one that a country actually follows. A de jure exchange rate system is the one that the country claims to follow. Both systems need not always be the same. China’s de facto system was the fixed rate but it insisted that its de jure system was a managed float. The IMF conducts surveys of exchange rate systems around the world. The surveys take into account both the de facto and de jure systems for each country.

Fixed versus Floating Exchange Rate:

Which exchange rate system is the best? The answer depends upon the objectives of the monetary authorities in a country.

There are three possible objectives:

i. Maintain stable exchange rates

ii. Allow mobility of capital

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iii. Have control over monetary policy.

With a floating exchange rate, the last two objectives can be attained but there will be exchange rate volatility. With a fixed exchange rate, the first two objectives can be attained but there will be no control over the monetary policy. In other words, irrespective of whether the fixed rate or the floating exchange rate is selected, only two of the three objectives can be attained. Thus, the three objectives are called the impossible trinity. In practice, countries can and do fine-tune their exchange rate systems, and need not choose either extreme.

Some countries (Canada, USA) consistently follow a particular exchange rate while others (Argentina, Russia) shift from one exchange rate to another. Canada has followed a flexible exchange rate since 1971, Hong Kong has had a currency board since 1983 and Argentina moved from a flexible exchange rate to a currency board in 1991. India moved from a fixed exchange rate to a partially floating rate in 1993 and a full float in 1994.

There has been a gradual shift from fixed exchange rate (and its variants) to flexible exchange rate. While a majority of developing countries had a fixed exchange rate in 1975, less than half had a fixed exchange rate 20 years later. Economists advocate a fixed exchange rate when an economy is affected by shifts in the demand for money that can affect price levels.

They advocate a flexible exchange rate when an economy is affected by changes in demand for products. A country that makes a successful transition from a fixed to a floating rate has a deep foreign exchange market, a well thought out policy of intervention by the central bank, and effective mechanisms to manage exchange rate risks.

The pegged exchange rate was popular in the early 1990s among countries that were making the transition to becoming market economies. Countries moved away from the hard peg towards the crawling peg. The efficacy of a particular exchange rate system is a function of each country’s unique economic circumstances, stage of development, strength of the financial system, and the degree of autonomy enjoyed by its monetary authority. No single exchange rate system has been an unqualified success across countries in terms of improvement in growth rates or financial stability.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The fixed exchange rate did not accelerate growth rates in countries that adopted it, nor did it protect them from currency crises. The same is true of the floating exchange rate. On the other hand, the central banks of many developing countries fear the impact a floating exchange rate would have through a sharp appreciation or depreciation of their currency on their exports and imports, as well as their capacity to repay overseas debt.

Exchange Rate Systems in Selected Emerging Markets (1980-2010):

The Brazilian real – The crawling peg was replaced by a floating exchange rate in 1990.

The Hong Kong dollar – It is on a currency board.

The Indonesian rupiah – The managed float was replaced by a floating exchange rate in 1997.

The Malaysian ringitt – The currency peg to a currency basket was replaced by a fixed exchange rate in 1998.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Phillipine peso – It is on a floating exchange rate.

The Singapore dollar – The currency peg to a currency basket was replaced by a fixed exchange rate in 1985.

The South Korean won – The currency peg to the US dollar was replaced by a managed float in 1980.

The Thai baht – It is on a managed float.

Differences between Flexible and Fixed Exchange Rate System:

Flexible Exchange Rate System:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Advantages:

1. It permits quicker adjustments in the exchange rate to changes in macro-economic factors such as changes in inflation rate, growth rate, and interest rates.

2. There is less likelihood of currency overvaluation. So the country’s growth prospects are brighter.

Disadvantages:

1. Exchange rate risk is high due to greater volatility in the short- and long-term. This makes exchange rate forecasting extremely important as well as extremely difficult.

2. There is a tendency for capital inflows through foreign portfolio investment, or ‘hot money’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Imports and overseas debt repayment are adversely affected by depreciation of domestic currency.

Fixed Exchange Rate System:

Advantages:

1. There is stability in exchange rate and exchange rate risk is nil.

2. Capital inflows through foreign direct investment are higher because there is no exchange rate volatility. FDI is a ‘desirable’ capital inflow due to its stable and long- term nature.

3. Inflation rates tend to be lower and therefore real interest rates (nominal interest rates adjusted for inflation) are higher.

Disadvantages:

1. The exchange rate does not reflect macro-economic changes. The entire foreign exchange entering and leaving the country has to be converted at the fixed exchange rate.

2. Punitive action for contravening rules.

In a fixed exchange rate regime, the entire institutional infrastructure is geared towards identifying evasion of foreign exchange controls and imposing penal punishments. A fixed exchange rate creates a flourishing parallel market for foreign exchange in which the ‘true’ value of the domestic currency is determined by market forces. This is because the par value of the domestic currency is very often at variance with what the exchange rate would be if left to the vagaries of supply and demand.

Very often countries fix a separate par value for exports and a separate one for imports. This is done to boost its exports and deter imports. This merely increase the draconian system needed to monitor foreign currency inflows and outflows.

The problems with a fixed exchange rate are described below:

1. The possibility of overvaluation of the domestic currency is quite high. Suppose the rupee is on a fixed exchange rate of Rs. 40/$ instead of Rs. 43/$ when left to market forces. So, instead of 1$ being able to buy Rs. 43 worth of goods, it can buy only Rs. 40 worth of goods). This would hurt the competitiveness of India’s exports and therefore hamper its growth prospects.

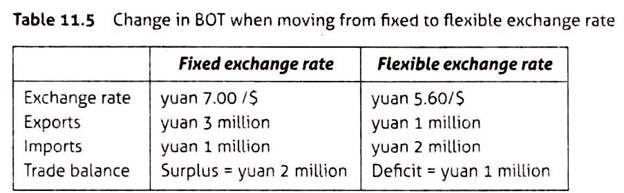

2. When the country on a fixed exchange rate is seen consistently to have trade surpluses, it generates a lot of ill will, and a perception that the trade surpluses are the result of currency manipulation of keeping the exchange rate artificially high (or low as the case may be). Consider the hypothetical example below. If the Chinese yuan should have an exchange rate of yuan 5.60/$ but is instead kept at yuan 7.00/$, Chinese exports have extremely competitive prices in world markets, and China has a trade surplus.

Sustained trade surpluses should make the yuan appreciate, and this should be reflected by moving the fixed exchange rate to yuan 5.60/$. The trade surpluses would decrease, and perhaps result in a trade deficit. This was USA’s argument for several years preceding the 2010 G20 Summit in Seoul. In Table 11.5, you can see the change in balance of trade (BOT) when the yuan-dollar exchange rate moves from fixed to flexible rate mechanism.

3. There is a loss of control over monetary policy. When a country is on a fixed exchange rate, inflows of capital lead to an increase in money supply and lending by domestic banks, whereas outflows of capital lead to contraction of commercial bank credit and money supply. When there are huge inflows, money supply in the country increases, and inflation rises. The central bank cannot contract money supply and rein in inflation because the country’s money supply is dependent on inflows and outflows unless the central bank undertakes sterilization of foreign exchange.

4. Regular intervention by the central bank in the foreign exchange markets to maintain the rigid peg could either lead to accumulation of enormous foreign exchange reserve by the central bank (as in China between 2001 and 2010) or a drain of the country’s foreign exchange reserves. When there are sustained foreign exchange inflows, sterilization causes the central bank to accumulate foreign exchange reserves.

China pegged its currency at 8.28 yuan/USD in 1998. Due to inflows of capital and a balance of trade surplus with the United States, the Chinese central bank (People’s Bank of China or PBOC) used government bonds and central bank bills to conduct sterilization, and had to purchase billions of US dollars to maintain the yuan/dollar peg. Sustained intervention can cause a depletion of foreign exchange reserves. The Thai baht was pegged to the US dollar. In 1997, speculative attacks on the baht forced the Bank of Thailand to sell $40 billion until all its reserves were depleted, and it was forced to abandon the peg.

5. Any instability in the anchor currency is immediately transmitted to the domestic currency. If a country’s currency is pegged to the US dollar, then all the ups and downs of the dollar become the ups and downs of the country’s currency. If the anchor currency’s value drops, so does the value of the country’s currency.

6. Market participants are unable to anticipate and manage exchange rate risk.

7. It is difficult for the country to make changes in fiscal policy and still retain overseas investor confidence in the economy. To make the country recover from recession, the standard fiscal response is to increase government spending. This is what USA did in the aftermath of the subprime crisis of 2007. But the US was on a floating exchange rate.

However, when a country on a fixed exchange rate increases government spending, overseas investors may view it as a signal that the country may not recover from the recession. It prompts capital to flow out of the country. So the fiscal policy response has an unintended consequence of increasing capital outflows.

8. The official exchange rate does not adjust quick enough to reflect the new purchasing power of the country’s currency.

9. A huge country on a fixed exchange rate, with massive surpluses, can destabilize the entire global financial system. China is a case in point—it faces a problem of plenty— its rising forex reserves have to be continuously invested. It chose to buy US Treasury Bills, and is now one of the largest overseas holders of US government bonds.

When US bond prices fell in 2009, China issued a veiled warning to the US asking it to ensure that its portfolio of US bonds does not lose more of its value. When China chooses to sell its US bond portfolio, it will result in a steep fall in US bond market prices quickly transmitting to stock markets in the US and around the world due to integration of financial markets, thus causing a meltdown in global stock markets, and severely destabilizing the financial markets.

Determination of Floating Exchange Rates:

There are four theories that explain how floating exchange rates are set. The first theory (the demand and supply theory) is called a flow theory because it studies how the demand for and supply of a domestic currency over a period of time results in a particular level for the exchange rate. The other three theories (the monetary theory, the asset price theory, and the portfolio balance theory) are called stock theories, since they study the amount of currency available at a certain time—the stock of currency—and peoples’ willingness to hold the currency. They are also called modern theories of exchange rate determination.

Supply and Demand Theory:

This theory states that the exchange rate is the intersection of the supply of domestic currency (shown as the supply curve) and its demand (shown as the demand curve). The supply of domestic currency is determined by imports and the demand is determined by exports.

Monetary Theory:

This theory links money supply and prices to the exchange rate. An increase in money supply leads to an increase in prices (inflation). According to the monetary theory, the exchange rate is the ratio of prices in two countries, so an increase in price causes the exchange rate to be reset. Consider two countries A and B. When the money supply in each country rises, the prices in each country rise. If the growth of money supply in A is greater than the growth of money supply in B, then A experiences a higher inflation rate than B.

According to the Purchasing Power Parity theory, the exchange rate is nothing but the ratio of prices between two countries. Since A has had a relatively greater rise in prices, A’s currency depreciates, will fall, and a new exchange rate will get established.

The monetary theory states that there is a direct connection between relative changes in money supply in two countries and the exchange rate between both countries, provided there are no transportation costs in moving goods between both countries.

Asset Price Theory:

The theory states that currency is an asset just as real estate or securities or gold. The desire to hold a particular type of asset is driven by the perception of the asset’s future value. If the value is likely to rise, people will want to buy the asset now and sell it at a higher price so as to make a profit. Conversely, if they think the asset’s value will drop, all those holding the asset now will start selling the asset fearing a greater decline in price in the near future. Therefore, the asset’s current attractiveness is a function of what the market believes its value is going to be in future. In other words, future expectations decide current buy/sell decisions.

This is true even for currency. If the market believes that the domestic currency is going to rise in value, everyone will start buying it. If the current exchange rate is Rs. 43/$, and the expectation is that the rupee will appreciate over the next six months. Participants will start purchasing the rupee and this will drive up demand. Because demand rises, the rupee will appreciate against the dollar, and the exchange rate will settle at Rs. 42/$.

If on the other hand, the market expects the rupee to depreciate, there will be selling pressure and the rupee will depreciate, probably settling at Rs. 44/$. At any point in time, the current exchange rate contains market expectations of the future value of the domestic currency.

Portfolio Balance Theory:

The portfolio balance theory connects money supply, supply and demand for domestic securities, demand for foreign securities, and the exchange rate.

Its assumptions are:

i. Investors can hold only two types of assets—currency and bonds (domestic bonds issued in domestic currency and foreign bonds issued in foreign currency).

ii. Investors in two countries have identical asset preferences.

iii. When the wealth of investors in either country increases, they would prefer to hold more of the asset that they already hold in excess.

Investors in two countries prefer to hold more of bonds in the country where wealth (value of the portfolio) is higher when translated into domestic currency. This is called the preferred habitat version of the portfolio balance theory. Changes in money supply affect wealth which in turn, has an impact on the exchange rate. Open market operations bring about changes in money supply.

When a central bank conducts open market operations by buying domestic currency-denominated government bonds, money supply increases and the domestic currency declines in value (depreciates) against the selected foreign currency and the exchange rate changes. When the central bank buys government bonds their supply decreases. But since the domestic currency has depreciated, the domestic currency value of foreign currency-denominated bonds rises. This makes investors prefer foreign bonds to domestic bonds, and the demand for domestic bonds decreases.