A derivative is an instrument that derives its value from an underlying asset.

The Foreign Exchange Management (Foreign Exchange Derivatives Contracts) Regulations 2000 defines a foreign exchange derivatives contract as a financial transaction or arrangement in whatever form or name, whose value is derived from price movement in one or more underlying assets and includes:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. A transaction which involves at least one foreign currency (other than that of Nepal or Bhutan).

ii. A transaction which involves at least one interest rate applicable to a foreign currency (other than that of Nepal or Bhutan).

iii. A forward contract

The definition excludes all three types of foreign exchange transactions in the spot market. The day on which the foreign exchange deal is entered into is called the trade date.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The above definition excludes transactions in which delivery of currencies occurs on:

1. The same day as the trade date (cash transaction)

2. The next business day after the trade day (TOM transaction, where ‘TOM’ stands for ‘tomorrow’)

3. The second business day after the trade date (spot transaction)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A derivatives market performs four important functions:

(i) It permits transfer of risk.

(ii) It boosts trading in cash market, through cash-futures arbitrage.

(iii) Under the monitoring of the market regulators, speculative trades are possible.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iv) Prices in the derivatives market reflect perception of market participants about future prices.

There are four currency derivative products:

1. Forwards,

2. Futures,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Options and

4. Swaps.

Several variants of options and swaps have emerged over time.

The important features of each type of contract are discussed below:

1. Currency Forward Contract:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), a forward contract is defined as ‘a transaction involving the exchange of two currencies at a rate agreed on the date of the contract, for value or delivery (cash settlement) at some time in the future (more than two business days).’

A currency forward contract has the following features:

(i) There is an exchange of two currencies at a pre-determined future date.

(ii) The delivery date is more than two business days after the trade date. The date on which delivery of currencies occurs is called the maturity date.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) The exchange of two currencies occurs at a pre-determined price called the forward rate.

(iv) The contract locks into a specific exchange rate, so the cash inflow or outflow is known beforehand.

(v) The contract is bilaterally negotiated.

(vi) Atleast one of the parties is a financial institution (most likely a bank). In a merchant deal entered into in the retail foreign exchange market, one party is an authorized dealer (AD) and the other is a client. In the inter-bank market, both parties are ADs.

(vii) Both parties mutually decide upon the currency pair, the amount of foreign currency to be exchanged, and the date of exchange. Therefore, the contract is designed to meet the unique requirements of the counter-parties.

(viii) The contract can be settled in one of the three ways – (a) The currencies are exchanged on the maturity date. (b) The contract is ‘closed out’ through an opposite spot transaction entered into before the maturity date. This creates a ‘net’ position for each of the counter parties. On the settlement date, only the net position is exchanged, (c) The contract is extended for a further period.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ix) Counter-party risk is high, because contract execution is not guaranteed. Counter party risk is also called Herstatt risk. It is so named because a German bank called Herstatt bank dishonoured its forward contract obligations in the 1970s.

2. Currency Futures Contract:

It is a contract entered into on a currency exchange to exchange two currencies at a pre-determined price, at a pre-determined future date.

The main features of a foreign exchange futures contract are:

i. It is an exchange traded product.

ii. A futures contract has a buyer and a seller.

iii. The exchange imposes rules with respect to the currency pair in which a futures contract is available, the minimum contract size, maturity and delivery dates. The buyer and the seller can enter into contracts only in the currency pairs that the currency exchange permits.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iv. Each futures contract involves a fixed quantity of a currency that varies from exchange to exchange. For example, buying a USD futures contract on the NSE would mean the buyer will have to purchase US$, 1000 on the delivery date and pay rupees at the pre-determined exchange rate. If he wants to buy Canadian dollars (CAD) 200,000 on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), where the contract size is CAD 100,000 he has to buy two CAD futures and pay US dollars at the pre-determined exchange rate. Similarly one yen futures refers to the purchase (or sale) of 12.5 million yen on the CME, and to the purchase (or sale) of 6.25 million yen on the Philadelphia Board of Trade (PBOT)

v. The buyer and the seller place their orders on the exchange just as they do in a stock exchange. The currency derivatives exchange guarantees each leg of the trade (leg 1 is between the buyer and the exchange and leg 2 is between the seller and the exchange).

vi. The exchange levies an initial margin on both the parties.

vii. The exchange specifies the maintenance margin for both the parties.

viii. Settlement can take place in one of the two ways:

(a) The buyer and seller exchange the currencies on the maturity date,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) The contract is closed out (or squared off) before the maturity date. The buyer and seller need not exchange the currency pair.

Each one of them can ‘close out’ his position, by entering into an opposite contract. That is if a person has agreed to sell yen on the CME, before this contract expires, he can enter into a contract to buy yen on the CME. Therefore, an ‘open’ position is a futures contract that has not been squared off.

ix. Every futures contract is marked to market (MTM). This is a process by which the exchange calculates the profit or loss to the buyer, and the profit or loss to the seller on every futures contract on a daily basis. This is done using the closing price prevailing on that day.

x. There is zero counter-party risk. The exchange’s clearing house guarantees that the contract will be executed.

Short Hedge:

It is the sale of futures contracts to protect oneself from a decline in price. Suppose an Indian exporter is about to receive $1,000,000 in two months’ time and enters into a futures contract to sell the dollars. He is said to be taking a short hedge.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Long Hedge:

It is the purchase of futures contracts to protect oneself from an increase in price. An importer has to make payment of €30000 in one month’s time for raw material imports. If he enters into a futures contract to buy euros, he is said to be taking a long hedge.

Margins in Futures Contracts:

The currency exchange imposes margins on both parties. Assume that a CAD futures on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) requires an initial margin of $2,000 and a maintenance margin of $500. A speculator buys a CAD future with 30 days to expiry, at a price of $0.75/CAD. The settlement price on day 0 (the day he entered into the futures contract) is $0.75/CAD. He deposits an initial margin of $2,000 with the CME. Similarly, the seller deposits an initial margin of $2000 with the CME.

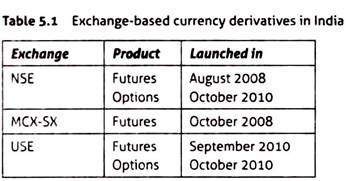

The CME notifies the buyer and seller of the daily balances in their margin accounts. If either the buyer’s balance or the seller’s balance falls below $500 (maintenance margin), then, the buyer or the seller (as the case maybe) has to deposit additional funds. Such settlement payments are called variation margin payments. Table 5.1 shows the different exchange-based currency derivatives available in India.

Marking to Market of a Futures Contract:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The currency derivatives exchange calculates MTM from the current day’s settlement price and previous day’s settlement price.

Comparison between forward and futures contracts in India:

Forward Contract:

i. Number of Parties to a Contract – Two (buyer and seller). One of the parties is an Authorized Dealer (AD)

ii. Trading – OTC (not on currency derivatives exchange)

iii. Counter-Party Risk – Though it exists, since CCIL guarantees settlement, it is reduced to zero

iv. Contract Regulation – No regulation

v. Standardization – No standardization. Contract size, delivery month and delivery date are mutually determined by both parties

vi. Currency Pairs Available in Indian Foreign Exchange Market – Any currency pair mutually agreed upon by the AD and the client

vii. Margin Requirements – None

viii. Marking to Market (MTM) – Does not occur

ix. Payment/Receipt of Funds – There are no intermediate cash flows. The cash flows occur only on the maturity date

x. Settlement – Usually by delivery of currencies on maturity date (with the exception of a non-deliverable forward contract, which is cash settled)

Futures Contract:

i. Number of Parties to a Contract – Two (buyer and seller). Both parties may be speculators, companies or ADs

ii. Trading – Exchange based – traded on the NSE, USE, and MCX

iii. Counter-Party Risk – Does not exist

iv. Contract Regulation – Reg by the concerned exchange

v. Standardization – Standardized contract. Contract size, delivery month and delivery date fixed by the exchange

vi. Currency Pairs Available in Indian Foreign Exchange Market – Only four currency pairs available in 2010 – US D/INR, €/INR, JPY/ INR and £/INR

vii. Margin Requirements – Initial margin Maintenance margin

viii. Marking to Market (MTM) – Conducted on daily basis

ix. Payment/Receipt of Funds – Takes place daily, due to MTM

x. Settlement – May be settled or closed off before the settlement date

Payoff Profile in a Futures Contract:

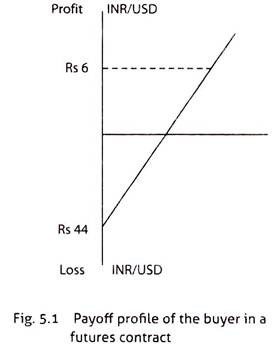

A payoff profile shows the graphical gain/loss on a futures contract. A buyer has limited potential loss and unlimited potential gain. A seller has limited potential gain and unlimited potential loss.

The maximum profit or loss of a buyer or seller in a futures contract is illustrated through an example. An Indian importer buys a one-month INR/USD futures contract at Rs. 44/$.

Compare this to four possible RBI reference rates that may prevail on the maturity date:

i. RBI Reference Rate is Zero:

The buyer can get dollars for free in the spot market. But, he has to pay the contracted Rs. 44, so his maximum loss is Rs. 44/$.

ii. RBI Reference Rate is Rs. 46:

The buyer can buy each dollar for Rs 46 in the spot market. But he has to pay only the contracted Rs. 44. So his notional gain is Rs. 46-44 = Rs. 2/$

iii. RBI Reference Rate is Rs. 50:

The buyer can buy each dollar for Rs. 50 in the spot market. But he has to pay the contracted Rs. 44, so his notional gain is Rs. 50-44 = Rs. 6/$

iv. RBI Reference Rate is Rs. 51:

The buyer can buy each dollar for Rs. 51 in the spot market. But he has to pay the contracted Rs. 44. So, his notional gain is Rs. 51-44 = Rs. 7/$.

Hence, the higher the RBI reference rate, the greater is the buyer’s notional gain. The limited potential loss and unlimited potential gain are shown in Fig. 5.1.

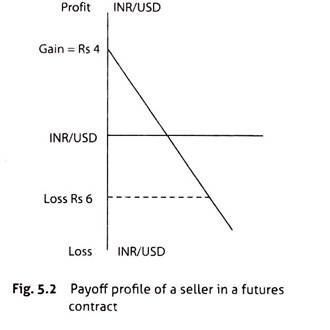

Suppose an Indian exporter enters into a INR/USD futures contract to sell dollars at Rs. 44/$. On the maturity date, the seller will receive Rs. 44.

Compare this to the four possible RBI reference rates that prevail upon the maturity date:

i. RBI Reference Rate is Zero:

The price of dollars in the spot market is zero. But he has contracted to receive Rs. 44/$. So his maximum gain per USD is Rs. 44. His maximum gain is limited to Rs. 44/$.

ii. RBI Reference Rate is Rs. 46:

The seller can sell dollars for Rs. 46/$ in the spot market. But he has contracted to receive Rs. 44. So his notional loss is Rs. 46 – 44 = Rs. 2/$

iii. RBI Reference Rate is Rs. 50:

The seller can sell dollars for Rs. 50/$ in the spot market. But he has contracted to receive Rs. 44. So, his notional loss is Rs. 50 – 44 = Rs. 6/ $

iv. RBI Reference Rate is Rs. 51:

The seller can sell dollars for Rs. 51/$ in the spot market. But he has contracted to receive Rs. 44. So, his notional loss is Rs. 51 – 44 = Rs. 7/ $.

So, the higher the RBI reference rate, the greater is the seller’s notional loss. His potential loss is unlimited. The seller’s limited potential gain and unlimited potential loss are shown in Fig. 5.2.

3. Currency Options Contract:

A foreign exchange options contract is one that ‘gives the right to buy or sell a currency in exchange for another currency at a specified exchange rate’ on a specified future date (European option) or ‘during a specified period’ (American option). Every contract has two parties—the buyer (called the holder) and the seller (called the writer). The holder acquires (or buys) the right but not the obligation, to buy or sell, a pre-determined quantity of a specific foreign currency for delivery at a predetermined future date for a pre-determined price.

If the buyer acquires (or buys) the right to buy a foreign currency, it is called a call option contract. If the buyer acquires (or buys) the right to sell a foreign currency, it is called a put option contract. The pre-determined price at which the buyer and seller agree to exchange a currency pair (either in a call option or a put option contract) is called the exercise price or strike price.

Features of Options Contracts:

(i) The date on which the exchange of currencies will take place is called the expiry date.

(ii) If the contract specifies that the buyer can exercise the contract only on the maturity date, it is called a European option.

(iii) If the contract specifies that the buyer can exercise the contract on any date up to and including the maturity date, it is called an American option.

(iv) The buyer decides whether the contract should be exercised on the maturity date (for a European option) or during the life of the contract (American option). Thus, an options contract is characterized by the right, but not the obligation of the buyer to exchange a currency pair.

(v) The buyer makes the decision to exercise his right by comparing the spot rate on the expiration date with the exercise price.

(vi) If the buyer decides to exercise the contract, he pays the writer the pre-determined exercise price (strike price).

(vii) The buyer pays the seller an option premium.

(viii) During the life of the option contract, depending upon the relationship between the strike price and the spot price on a given day, an option is ‘in the money’, ‘at the money’ or ‘out of the money’.

An option contract (whether call or put, American style or European style) may be traded on a currency derivatives exchange (exchange-traded contract) or as an OTC contract. Thus, we can have an OTC European call option contract or an exchange-traded American put option contract. Similarly, other combinations are possible, and in each case three variables decide the nature of the options contract—when it is exercisable, whether it is exchange traded, and what the buyer wants to do (buy or sell).

In an exchange-traded options contract, the currency derivatives exchange decides the spot month, the maturity date, the currency pairs that can be exchanged, and the minimum contract size. But an OTC options contract is tailor-made to suit both the parties. Contract specifications are similar to those for foreign exchange futures contracts. Hence, exchange- based foreign exchange options contracts are standardized, and give little freedom to the holder and the writer.

An exchange-traded contract is known by the month in which the contract matures. So a September call options contract matures in September and a June put options contract matures in June. The exercise date is the designated date on which the contract matures, and is specified by the exchange (such as the third Wednesday, or third Friday of the expiry month, as the case maybe). Market participants have devised many variants of the call and put option.

Option Premium:

The seller is a passive party in an option contract. Why would he enter into such a contract, and what does he get out of it? In every options contract, the buyer has to pay the seller the option premium, also called the price or market value (denoted by P). The seller gets to keep this amount whether the buyer honours the options contract or not. The premium may be expressed as a unit of currency (say US$0.001) or as a percentage. In the latter case, it is calculated as a percentage on the spot price on the day the buyer enters into the contract.

On the maturity date, the buyer of a call option contract will exercise his right when the spot price (S) is higher than the exercise price (E), i.e., S > E. The buyer of a put option contract will exercise his right when S < E. Such contracts are said to be ‘in the money’.

Depending on whether S is equal to E, greater than E, or less than E, each option contract is referred to by a specific name.

A call options contract is said to be:

‘in the money’ when S > E

‘at the money’ when S = E

‘out of the money’ when S < E

A put options contract is said to be:

‘out of the money’ when S > E

‘at the money’ when S = E

‘in the money’ when S < E

Since the value of S changes every day, an ‘out of the money’ option can become an ‘in the money’ option and vice versa, over its life.

Intrinsic Value:

The option premium (P) consists of two elements called the intrinsic value (F) and the time value (T).

Depending upon the type of option contract, the maximum value of F is:

V = Maximum of (S – E, 0) for a call option

V = Maximum of (E – S, 0) for a put option

(i) An ‘in the money’ call option has a positive intrinsic value (S > E), an ‘at the money’ call option has zero intrinsic value (S = E), and an ‘out of the money’ call option also has zero intrinsic value (S < E), but V = Max (S – E, 0).

(ii) An ‘in the money’ put option has positive intrinsic value (S < E), an ‘at the money’ put option contract has zero intrinsic value (S = E), and an ‘out of the money’ option has zero intrinsic value (since S > E) but V = Max (E – S, 0).

The breakeven price is that at which the option premium is equal to the intrinsic value. It is a no profit-no loss point for the buyer and the seller.

For a call option contract, breakeven price is that at which P = (S – E)

For a put option contract, breakeven price is that at which P = (E – S)

Time Value:

The time value of an option contract is the difference between the option premium (P) and the intrinsic value (F).

The time value of a call option is (P – V) = [P-(S – E)]

The time value of a put option is (P – V) = [P – (E – S)]

The time value is defined as the possibility that the intrinsic value could be higher over the life of the option contract. Thus, the time value of a 3-month option contract is larger than that of a 1-month options contract. As an options contract approaches maturity, its time value decreases and on the maturity date, the option has no time value.

European Style Call Option Contract:

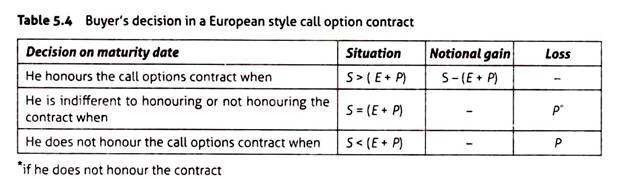

Given the exercise price (E), the spot price on the maturity date (S) and the option premium (P), the buyer’s decision to exercise the contract depends upon the relationship between S, E and P.

Buyer of a Call:

The buyer (or holder) of a European style call option has to pay the seller the option premium (P) and the exercise price (E). If the buyer does not honour the contract, he will forfeit the premium (P). The buyer will decide to exercise the contract depending upon the relationship between S and (E + P). Table 5.4 summarizes his decisions. The gain to the buyer of a call option is calculated as S – (E + P).

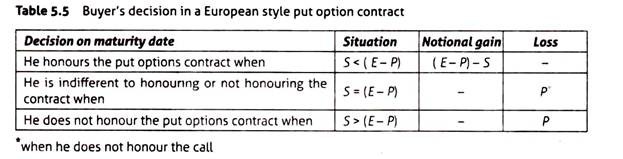

Buyer of a Put:

The buyer (or holder) of a put option has the right to sell a currency, and receive the exercise price (E). He also pays an option premium (P) to the seller. If the buyer exercises the contract, his total payment to the seller is E – P. If the buyer does not honour the contract, he will forfeit the premium (P). The buyer will decide to exercise the contract depending upon the relationship between S and (E – P). As shown in Table 5.5, the buyer will exercise the put options contract when S < (E – P). If the buyer exercises his option, what is his gain? It is calculated as (E – P) – S.

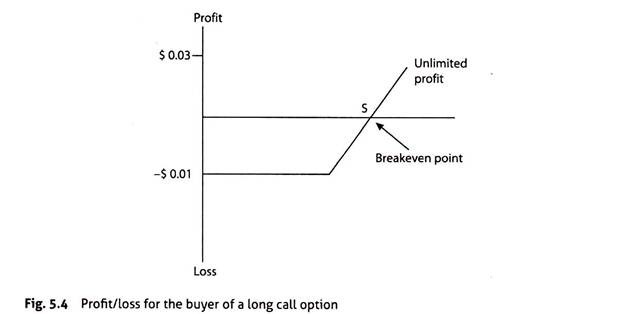

Payoff Profile for the Buyer of a Call Option:

A payoff profile depicts the profits and losses on the contract at a specific point in time. What is the maximum loss for the buyer and the maximum gain?

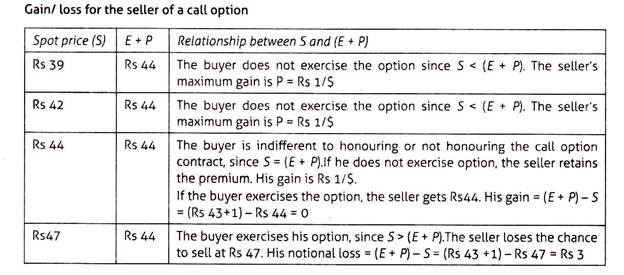

Payoff Profile for Seller of a Call Option:

What about the writer of the call? Let us consider the writer of one-month December call option contract on USD/INR with a strike price of Rs. 43, and a premium of Rs. 1, faces four different spot prices on the maturity date – Rs. 39, Rs. 42, Rs. 44 and Rs. 47 respectively.

E = Rs. 43; P = Rs. 1; E + P = Rs. 43 + 1 = Rs. 44

Seller’s notional loss = (E + P) – S

Seller’s gain = P

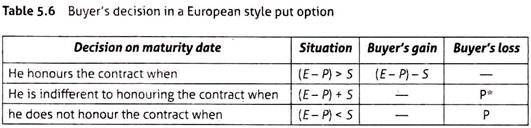

Buyer of a Put Option:

The buyer of a European style put option has the right but not the obligation to sell a currency on the maturity date. The buyer exercises the put when S < E. The buyer pays the premium (P) and receives the exercise price (E).

Buyer’s gain = (E – P) – S or E – (S + P)

If the buyer does not exercise the option, he forfeits the premium. His maximum loss is limited to the premium (P). Thus, the buyer has limited loss and unlimited gain.

What about the seller? His gain or loss would depend upon the buyer’s actions:

(i) If the buyer exercises the put (it means S is lower than E). The seller is forced to pay E when he could have paid much lesser in the spot market. The seller pays the exercise price (E) and receives the premium.

The seller’s net payment = (E – P)

The seller’s loss = (S + P) – E

(ii) If the buyer decides not to exercise the option, the seller receives the premium.

The seller’s gain is limited to the premium. He has limited gain and unlimited loss. Table 5.6 summarizes the gain or loss for the buyer’s decisions.

4. Currency Swap Contract:

A currency (or foreign exchange) swap, according to the BIS is ‘a transaction which involves the actual exchange of two currencies (principal amount only) on a specific date at a rate agreed at the time of conclusion of the contract (the short leg) and a reverse exchange of the same two currencies at a date further in the future and at a rate (generally different from the rate applied to the short leg) agreed at the time of the contract (the long leg).’

A swap has the following features:

(i) It is a contractual agreement between two parties to exchange (or swap) cash flows in two different currencies.

(ii) It is an OTC contract bilaterally negotiated by two parties (called counter-parties). One of them is usually a commercial bank (an authorized dealer which is also a market maker). The cash flows may relate to a loan—exchange of principal, exchange of the periodic interest and the re-exchange of principal.

(iii) The counter-parties desire cash flows in a different currency than the one they have got, and both parties stand to gain from the swap.

(iv) A middleman (a bank, broker, or dealer) brings the counter parties together and tailors the swap deal to meet the requirements of both parties. The middleman is called a swap bank (if it is a commercial bank) or swap facilitator.

(v) Very often the swap facilitator is also a counter-party in a swap deal. Commercial banks have numerous swap deals in different currencies (called a swap portfolio) in each of which the bank is a counter-party. A commercial bank may seek a swap contract with another commercial bank. Therefore, the counter-parties can be two companies (the deal being put through by a swap bank), a company and a bank, or two banks.

(vi) The exchange of cash flows could be:

(a) The sale of one currency against another in the spot market and a simultaneous repurchase of the first currency in the forward market.

(b) An initial exchange of principal and final re-exchange of principal on the maturity date.

(c) An exchange of several streams of interest payments.

(vii) The dates on which both parties will exchange cash flows during the life of the swap contract are called the settlement dates or value dates.

(viii) The first exchange of currencies is called origination. It is done at the spot exchange rate prevailing on that date.

(ix) The date on which the counter-parties enter into the swap contract is called the trade date.

(x) The date on which the contract is completed (or ceases) is called the maturity date or the far date.

Combinations of Derivatives Products:

In practice, market participants combine any two derivatives contracts to come up with a third product—examples include the kick in forward, the break forward and the puttable swap. The combination is limited only by the imagination, and the requirements of the parties to a derivatives contract. The combinations are not exchange-traded products, and brokerage houses and international banks design such currency derivatives products for a particular client. If the product becomes successful, it is widely imitated otherwise it is a one-off product.