Read this article to learn about the Marketing Strategy. It’s meaning, types, process, dynamic aspects and conclusion.

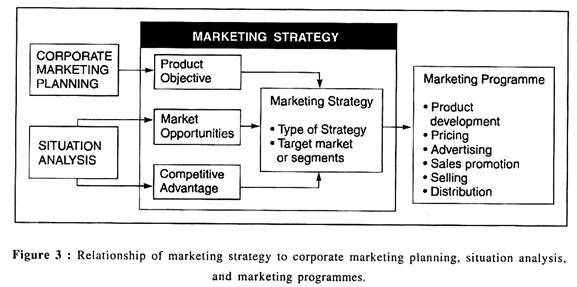

Marketing strategy is the bridge between corporate strategy and the situation analysis on the one hand and the action-oriented marketing programmes on the other.

Marketing Strategy: Meaning, Types, Process, Aspects and Conclusion

1. Marketing Strategy: Meaning

Marketing strategy is the bridge between corporate strategy and the situation analysis on the one hand and the action-oriented marketing programmes on the other. Marketing programmes should flow from and be consistent with the marketing strategy.

In this part, we examine the various types of marketing strategies that can be chosen, present a process for selecting a marketing strategy, and discuss some important dynamic aspects of marketing strategy.

2. Marketing Strategies: Types

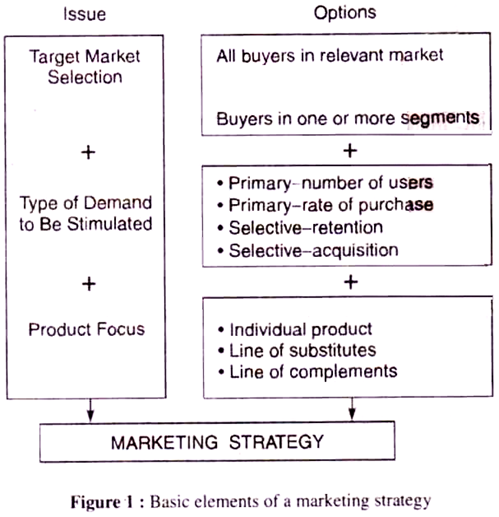

The chart below portrays the basic elements involved in a marketing strategy.

A. Primary-Demand Strategies:

Primary-demand strategies are designed to increase the level of demand for a product or class of products by current non-users or by current users.

There are two fundamental strategic approaches for stimulating primary demand:

(i) Increasing the number of users, and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Increasing the rate of purchase.

A. 1 Strategies for Increasing the Number of Users:

The firm, in order to achieve this, must increase:

(a) Customers willingness to buy or

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) Their ability to buy the product or service, or both.

(a) The Willingness to Buy may be stimulated by one of three approaches:

1. Demonstrating the benefits already offered by a product

2. Developing new products with benefits that will be more appealing to certain segments

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Demonstrating or promoting new benefits from existing products

A focus on demonstrating the basic product-form benefits is often necessary when a new product form is being marketed. For instance, Procter & Gamble had to demonstrate the convenience and performance of disposable diapers to markets in which washing cloth diapers was a time-honoured behaviour.

The importance of this strategy type is paramount when a new product form or class is introduced, because new products seldom sell themselves.

Thus, in the developing countries like India, Procter & Gamble emphasise the basic advantages of disposable diapers in order to stimulate primary demand.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) The ABILITY TO BUY can be improved by offering lower prices or credit or by providing greater availability (through having more distributors, more frequent delivery, or fewer stock outs). For example, reduced prices brought the cellular phone market rapid sales increases in the mid-1990s.

A.2 Strategies for Increasing Rates of Purchase:

When marketing managers are concerned with gaining more rapid growth in a sluggish but mature market, the marketing strategy may be geared towards increasing the willingness to buy more often or in more volume, using one of the following approaches.

(a) Broadening Usage:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Buyers may expand usage if the variety of uses or use occasions can be expanded. In recent years, a number of advertising campaigns have been conducted to suggest broadened uses for products or services. For example, Coca-Cola’s advertising campaign suggests ‘Coke in the morning’.

(b) Increasing Product Consumption Levels:

Lower prices or special-volume packaging may lead to higher average volumes and possibly to more rapid consumption for products such as soft drinks and snacks.

Or, consumption levels may be stimulated if buyers’ perceptions of the benefits of a product or service change. Following this sub-strategy, American Express expanded the benefits of its card to include automatic insurance of products that are purchased using the card.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) Encouraging Replacement:

Product redesign may be thought of as a selective-demand strategy. It is, however, largely a primary-demand strategy in the fashion industry and in other durable-goods industries. Although a refrigerator or a TV may well last 20 years, many replacement sales will be made earlier if product convenience, product quality, product features, space utilisation, and operating cost can be improved.

Although these strategies are not widely used than the selective-demand strategies, they can be extremely useful if market measurements show large gaps between market potential and industry sales.

B. Selective-Demand Strategies:

Selective-demand strategies are designed to improve the competitive position of a product, service, or business. The fundamental focus of these strategies is on market share, because sales gains are expected to come at the expense of product-form or product-class competitors.

These strategies can be accomplished either:

(i) By retaining existing customers (i.e., Retention strategies) or

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) By acquiring new customers (i.e., Acquisition strategies).

In particular, if industry sales are growing slowly and yet are close to market potential, managers desirous of building sales can only do so by acquiring competitors’ customers.

However, when the industry growth rate is high, sales and market share can also be increased by acquiring customers who have the ability and willingness to buy but who are just entering the market. For example, new mothers and persons moving into a new location may be new buyers for a diaper-rash product and a local bank, respectively.

Retention strategies, on the other hand, are more likely to be used by firms with a dominant share of the market and by small-market-share firms with entrenched positions in particular segments. Moreover, both retention and acquisition can be segment-specific. Managers may decide to focus the marketing effort on one or on a limited number of target segments, even when a firm currently operates in several segments.

B. 1 Acquisition Strategies:

A firm cannot acquire competitors’ customers or new customers unless it is perceived by buyers as more effective in meeting customer needs. Because buyers’ choices will largely be based on their perceptions, customer acquisition strategies will essentially be based on how the product is to be positioned in the market.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

That is, a product’s position represents how it is perceived relative to the competition of the determinant attributes desired by each segment.

From a managerial perspective, a firm has two basic strategic options:

(a) Head-to-head positioning or

(b) Differentiated positioning.

(a) Head-To-Head Positioning:

With this strategy, a firm offers basically the same benefits as the competition but tries to outdo the competition either by superior quality or by price-cost leadership. For example, IBM in 1992 entered the notebook category of the personal computer market with a colour screen that is larger and clearer than competing notebook PCs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Other ways of conducting a head-to-head positioning strategy include outspending the competition on advertising (so your brand has better awareness) or offering wider availability or faster delivery.

Alternatively, firms may compete primarily on a price basis by offering comparable quality at a lower price.

Importantly, although leading firms often have economies of scale that yield cost advantages, small firms can sometimes succeed on price leadership.

Comments:

Marketing managers should avoid head-to-head competition, for if the similarity among competitors’ marketing strategies is very strong, several common marketing problems can result.

First, if several brands have a common market offering, they are collectively more vulnerable to aggressive new entrants who offer a different benefit of equal value.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Second, these commonly positioned brands usually must spend more than unique or niche products to gain support from retailers or other distributors.

(b) Differentiated Positioning:

In differentiated positioning, a firm is trying to distinguish itself either:

(i) By offering distinctive attributes or benefits by catering to a specific customer type (i.e.. Attribute positioning),

(ii) Or by separating itself from other competitors by serving one or limited number of special segments in a market (i.e., Customer-oriented positioning).

(i) Attribute Positioning:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In benefit/attribute positioning, firms emphasise unique attributes (such as Gillete Presto shaver, unique packaging advantages (Lipton, Cup-A-Soup), or unique benefits (A refrigerator with double door). Often, a product does not offer a unique attribute but a unique combination of attributes. Lever 2000 bar soap was successful because it combined a deodorant benefit with a moisturising benefit.

(ii) Customer-Oriented Positioning:

In customer-oriented positioning (also known as niche), a firm tries to separate itself from major competitors by serving one or a limited number of special segments in a market. Often, niches are defined in terms of particular buyer characteristics.

For example, Zenith first entered the personal computer market by focusing solely on government agencies and universities. However, niches can also reflect specialised buyer needs: Thakurpukur Cancer Research Centre for cancer patients or BM Birla Heart for cardiac patients or Sushrut Eye Foundation accepting eye-patients.

Finally, niche can be based on the development of a unique product usage situation. For example, The Progressive English Dictionary of 1952 (pocket edition) by Oxford University Press was possibly the first one designed for frequent use.

Increasingly, firms in complex industries with a wide variety of products have engaged in customer-oriented positioning. Many such firms are in the entertainment industries. Today, for instance, many movies are niche products.

B.2 Retention Strategies:

Increasingly, managers have begun to recognise that it can be more profitable to retain existing customers than to search for new ones.

In order to influence a customer to stay with a brand or supplier, marketers have three basic strategic options:

(a) Maintain a high level of customer satisfaction.

(b) Meet competitors’ offerings.

(c) Establish a strong economic or interpersonal relationship with the customer.

(a) Maintain Satisfaction:

Many well-established brands with dominant market shares focus their strategies and programmes on maintaining customer beliefs regarding the superior quality of the product.

Satisfaction with product performance can also be enhanced if a firm provides additional information or services that will lead to proper and effective use of the product. Industrial marketers frequently offer maintenance, repair, and operating (MRO) services to enhance satisfaction, and many consumer-goods firms offer similar programmes.

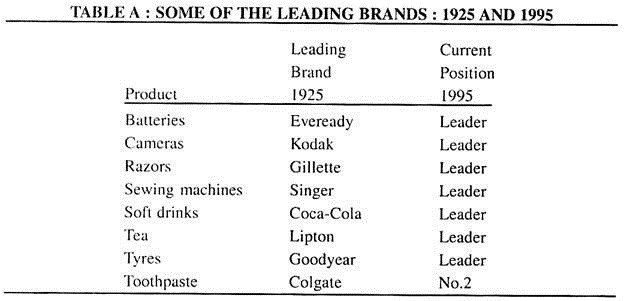

The importance of product satisfaction has been argued as one of the reasons for the long-term market leadership of many brands (as displayed in Table A). Research conducted by the Boston Consulting Group and Advertising Age magazine suggests that the loyalty achieved from value-based consumer brands is the most enduring of all competitive barriers.

(b) Meeting Competition:

While maintaining satisfaction is always an important goal, competitors often are able to provide satisfactory products and services. And they may offer more options and features, lower prices, and advertise heavily. Based on research conducted in several industries, the best defensive strategy to a competitive attack on product quality, price, or heavy advertising is to meet (or even surpass) the competition.

Additionally, some firms often find that they must match competitors in terms of the number of product-line options offered.

(c) Relationship Marketing:

A relationship marketing strategy is designed to enhance the chances of repeat business by developing formal interpersonal ties with the buyer. Long-term relationships are often established through contractual or membership arrangements with customers or distributors. Typically these arrangements are only successful because of some discount or an economic incentive associated with the cost of purchasing.

For example, consumers who buy season tickets for Annual Music Conference (Dover Lane, Kolkata) series are essentially engaged in a membership relationship. Similarly, annual fees charged by Medicare (insurer) ensure at least a 1-year relationship.

In industrial marketing, simplification programmes such as long-term protection against price increases or inventory management assistance frequently are so desirable to buyers or to distributors that they will commit themselves to use one supplier as the sole source of supply for a period of time.

Another recent development involves the placement of computer terminals (and often, associated software) in customers’ offices. These terminals are then hooked into the sellers’ terminals, enabling customers to order products instantly (and thus better manage their inventories), check on the progress of deliveries, and obtain technical assistance.

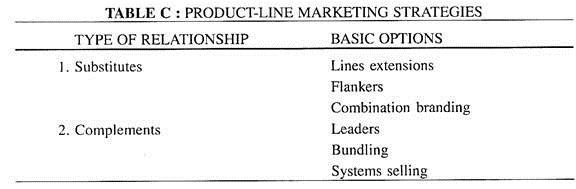

C. Product-Line Marketing Strategies:

Most firms offer a line of products that are closely related because they serve similar needs, are used together, or are purchased together. Products that serve the same basic need are functional substitutes for one another. Thus, the various investment schemes offered by a bank (savings accounts, money market accounts, certificates of deposit) are substitutes.

Products that are used together or purchased together and serve related needs are complements. For a bank, current accounts, savings accounts, and credit cards are all complementary.

Increasingly, firms are developing strategies that take these relationships into account. Developing a marketing strategy for each individual product without considering the impact of that strategy on substitutes or complements can lead to undesirable results.

C.1. Strategies for Substitutes:

Increasingly, firms that offer a line of substitute products attempt to focus on the entire line. This practice, sometimes known as category management, is expected to result in a more effective use of resources across products in the line.

Two important strategic issues in category management are:

(1) The setting of product-line prices and

(2) Branding strategy.

Basically a firm has three kinds of brand strategies to choose from:

(a) Line extensions,

(b) Flanker brands, and

(c) Combination brands.

(a) Line Extensions:

A line extension is a variation of an existing product that retains the brand name while offering modestly new or different features. For example, Liquid detergent is a line extension.

The major advantage of the line extension strategy is that the brand’s existing equity is leveraged and so it becomes easier to gain market acceptance for the new product. A drawback is that the new product will probably be most appealing to the existing users of the brand, resulting in a greater likelihood of cannibalism.

Note:

The possibility of cannibalism must be considered with the strategy. Cannibalism occurs when sales of a new product are derived at the expense of existing products in the company’s list of offerings. Hence, a product that takes sales from another offering in the same product line is said to be cannibalising the line.

Companies that have several similar products often position a new product so that it does not erode sales of, or cannibalise, its earlier brands. Although it is acceptable for a new product to take sales from an existing product, it is essential for the new offering to produce sufficient additional sales in order to warrant the investment.

(b) Flankers:

A flanker brand is a new brand designed to serve a new segment of the market. For example, American Express introduced the Optima card as an addition to its green and platinum cards, which carry the American Express logo.

Unlike its traditional cards, Optima offers a revolving line of credit, much the way VISA and MasterCard are used. Many marketers expect that this will reduce the degree to which existing brands are cannibalised. Additionally, a flanker strategy will enable a firm to establish a new position or image that may be necessary to succeed in the new segment.

(c) Combination Brands:

Often firms try to obtain the advantages both of brand leveraging and of new brands by creating a new brand personality within the original brand family. With combination branding, the core qualities of the family brand equity are retained to reduce the customer’s perceived risk, but at the same time, a new personality is developed to underscore the distinctiveness of the new offering.

This strategy is likely to be useful if a new segment is being targeted, a different set of benefits is offered, or a new price quality level is being introduced.

For example, the Gillette Sensor needed to be distinguished from Gillette’s other shaving products because of its significantly enhanced technology (and higher price). At the same time, Gillette’s reputation for quality shaving products clearly enhanced the rate of consumer acceptance.

C.2 Strategies for Complements:

These marketing strategies are sometimes directed towards retaining customers in support of a relationship marketing strategy. For example, many financial institutions try to get ‘savings account’ customers to use the institution as a source for their credit cards, loans, fixed and deposit accounts.

Three basic complementary strategies can be identified: leaders, bundling, and systems selling.

(a) Leaders:

In a leader strategy, a firm promotes or prices one particular product very aggressively in the expectation that buyers will also purchase complementary goods or services. For example, a low price on a major appliance may result not only in increased sales of that appliance but in more sales of service contracts as well.

(b) Bundling:

A bundling strategy involves the development of a specific combination of products sold together, usually at a price that is less than the sum of the prices if the products are sold separately. Thus, a bank may offer a credit card at no annual fee to bank customers who maintain large certificate of deposit accounts.

This strategy can be effective when buyers have a very strong preference for the product being discounted and a need but no strong brand preference for the product purchased at full price. Additionally, bundling and leader strategies are effective when customers can save time by buying the set of products from a single source.

(c) Systems Selling:

In systems selling, a firm emphasises that individual products are designed to be highly compatible with one another. For example, a computer manufacturer may design personal computers that are very technically compatible with its mainframe computers.

Thus, mainframe customers who want to purchase PCs that will be able to communicate with the mainframe (to form a system) will be more likely to buy the most compatible equipment.

It is important to recognise that product-line marketing strategies are really special cases of the primary and selective demand strategies. That is, any product-line strategy is directed at influencing either primary or selective demand. However, this class of strategies can be used to increase different types of demand in different situations.

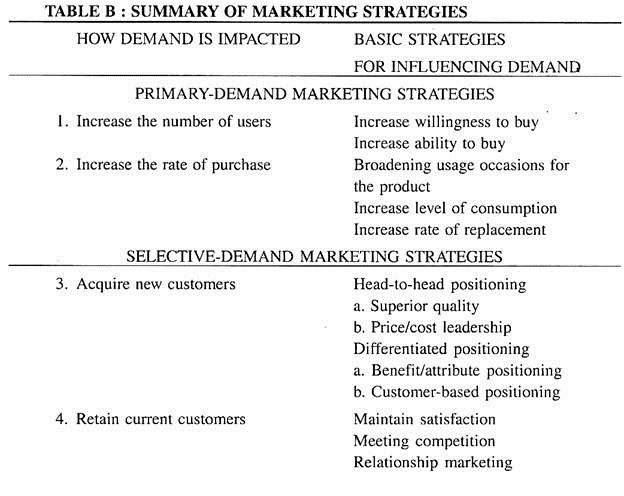

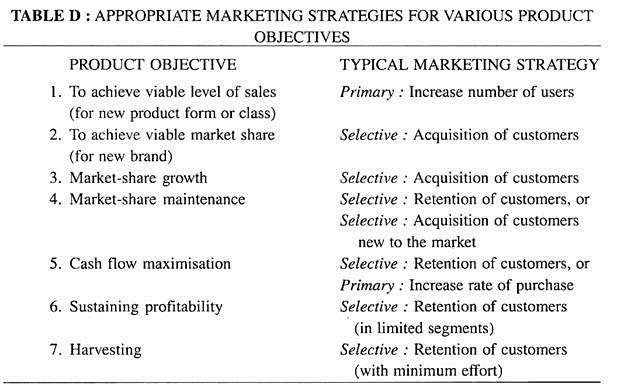

The different marketing strategies are summed up below:

3. Marketing Strategy: Process

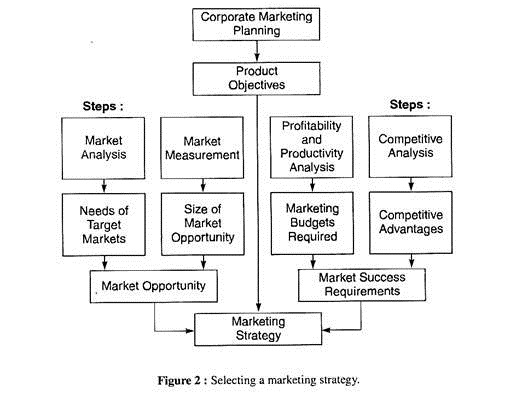

To choose the best marketing strategy, a manager must consider several kinds of information (see Figure 2).

First, the marketing strategy must be consistent with the product objective.

Second, the nature and size of the market opportunity should be clearly established based on the market analysis and market measurements.

Finally, managers must understand what kinds of competitive advantage and marketing expenditure levels will be necessary to achieve market success.

The Role of Product Objectives:

The Role of Product Objectives:

Product objectives help determine the necessary basic type of strategy. For example, if market-share objectives are important, managers will employ selective-demand strategies to retain or expand market share. Alternatively, the greater the importance of cash flow and profitability objectives, the more likely a manager will be to select retention strategies and strategies for increasing repurchase rates.

That is, these strategies will, in general, be less costly than acquisition strategies or strategies aimed at increasing the number of users. (Put simply, it is usually easier to reach and persuade existing brand customers and existing product-form buyers than to convert competitors’ customers and non-adopters.)

Table D summarises the general types of marketing strategies that managers should typically use to achieve a given product objective. Managers can, however, use more than one strategy simultaneously if adequate resources exist. Of course, in selecting a strategy, managers must also consider any impact the strategy may have on complementary or substitute products.

Additionally, the feasibility of a given strategy depends on the firm’s ability to deal with the problems and opportunities identified in the situation analysis. If managers cannot identify a feasible marketing strategy for implementing the product objective, then the objective probably should be modified.

Implications from the Situation Analysis:

Each of the issues having impact on situation analysis has implications for the selection of marketing strategies and programmes.

1. Market analysis provides information on who buys (and who does not buy) the product form, the various situations in which the product is used (or not used), and the factors influencing the willingness and ability to buy. This information can help managers select strategies and programmes for increasing either the number of users or the rate of use.

By analysing selective demand, managers should gain insights into the alternative segmentation opportunities that exist and the factors influencing buyer-choice processes.

2. The competitive analysis enables a manager to determine who the competitor will be, how intensive the competition will be, and what advantages must be developed in order to compete effectively either against direct brand competitors (in selective-demand strategies) or against indirect product-class competitors (in primary-demand strategies).

3. Market measurements provide information on the size of the primary-demand gap between market potential and industry sales. The larger this gap, the greater the opportunity to expand primary demand for a product form or class.

Further, the slower the industry sales growth, the more important it will be to find ways of expanding primary demand. Company sales forecasts with cause-wise analysis can provide insights into the impact of various marketing programmes on sales.

4. By combining productivity estimates with profitability analysis, managers can determine the profit consequences of the strategies and programmes required for achieving market-share objectives.

5. Basic market-share strategies may be classified into three categories:

6. Building strategies based on active efforts to increase market share when it is not high enough to yield satisfactory returns. This effort often requires substantial contributions by means of increasing marketing programmes and expenditure.

7. Holding strategies aimed at maintaining the existing level of market share, particularly for companies in relatively mature markets.

8. Harvesting strategies designed to achieve high short-term earnings and cash flow by allowing market share to decline. This cash can be used to support another product line or marketing decision.

4. Marketing Strategy: Global Context

Because an increasing proportion of businesses operate across national boundaries, an important question is whether to market a single standardised (and thus globalised) offering or to treat the various nations in the market as segments.

If the latter (and more traditional) course of action is taken, the strategy is similar to a product-line flanker strategy. At the opposite extreme, a single brand is marketed with the same marketing programmes in all nations.

The principle of selling the same product in essentially the same way everywhere in the world is not new. Caterpillar adopted a global approach to its marketing after World War II, and organised an international network to sell spare parts and built a few large-scale efficient manufacturing plants in the United States to meet worldwide demand.

The product was then assembled by smaller regional plants, which would add those features that were needed for local market conditions. The emergence of global markets has allowed corporations as diverse as Revlon (cosmetics), Sony (televisions), and Black & Decker (power tools) to standardise manufacturing and distribution.

Some concessions to cultural differences—such as producing cars with steering columns on the right or left side—are made, but these require only minor modifications, and most other features of the product remain the same.

In the early 1980s, Professor Theodore Levitt of the Harvard Business School declared the global approach to be appropriate for all firms.

He argued that advances in communication, transportation, and entertainment technology were bringing about more homogeneous world tastes and wants. Companies that failed to adopt a global strategy were seen as vulnerable to global firms that could obtain savings from standardisation.

In reality few firms are totally globalised in terms of the full marketing mix. Even the largest multinationals with established worldwide images make some local adjustments.

For example, Coca-Cola introduced Diet Coke with a globalised name, concentrate formula, positioning, and advertising but varied the .artificial sweetener and packaging across nations. The basic strategic issue is how much customisation is necessary and desirable.

Among the factors favouring globalisation, four stand out as most significant:

1. Economies of scale exist:

The greater the economies of scale, the more advantageous a global strategy. The rapid increase in globalisation for autos and construction vehicles reflects such economies.

2. Product usage is stable across cultures:

Some products (particularly those within the home) may not be consumed in comparable ways or rates by people in different cultures. For example, canned soup can be condensed for the North American market but is unacceptable in that form in Europe and Asia. In such cases, product or positioning variations are appropriate.

3. The same competitors exist across markets:

To the extent competitors are global, a firm will likely have to compete in the same way in each market.

4. Many of the firm’s key customers operate globally:

Because so many large firms are multinational, the firms that sell to these multinational customers must offer the same basic strategy in each market. Thus, IBM, and Nippon Steel are likely to be heavily globalised. To the extent that these conditions exist, globalisation seems to be an appropriate strategic direction.

Increasingly, it appears that the globalisation strategy is driven by a combination of scale economies and the challenge of competing with the same customers across many markets.

5. Marketing Strategy: Dynamic Aspects

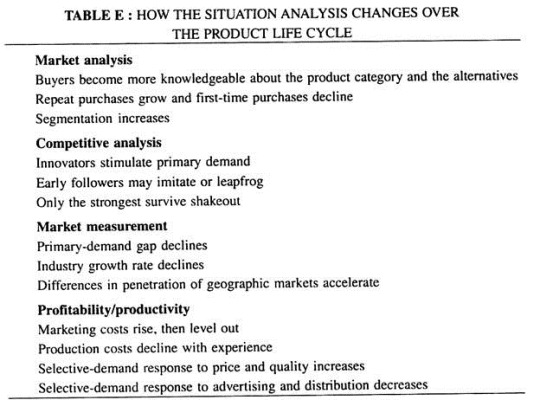

A firm must usually change its strategy over time because the situation it faces will change. The product life cycle provides managers with guidance as to how the situation changes over time. These changes (which are summarised in Table E) will have an impact on both the choice of a strategy and the selection of marketing programmes for implementing the strategy.

The Product Life Cycle and Strategy Selection:

The most obvious impact of the product life cycle is the shift from a primary-to a selective-demand strategy as the life cycle shifts from the introductory stage to the growth and maturity stages. As buyers become more knowledgeable about the product category and as the primary-demand gap declines, the need for and payoff from primary-demand strategies decline.

A second consideration is that retention strategies should seldom be relied on, even by a market leader, until the life cycle is well into maturity. As long as markets are growing rapidly, acquisition strategies are important.

Third, product-line extensions and flankers should be developed as soon as segmentation opportunities arise. While some marketing consultants have argued that such products should be used to try to reinvigorate life cycles in maturity, the conventional wisdom is now changing.

Often line extensions are necessary to move a product through the growth stage because the variation in basic customer needs (for example, personal computers or microwave ovens) is very large. Additionally, market leaders who offer a full product line may pre-empty competitive opportunities from new entrants or be better able to meet competitive challenges.

Product Life Cycle/Marketing Programmes and their Impact on Market Share:

From the foregoing discussions, one would find that a given type of marketing strategy may be achieved through two or more different marketing programmes. For example, acquiring new customers through head-to-head positioning could imply direct competition on price, availability, quality, or brand awareness.

However, over the course of the life cycle the productivity of different programmes changes. Specifically, as the life cycle moves from introduction towards maturity and decline, the following trends in the response of market share occur.

Price:

The impact of price on primary demand is usually very high during introduction. But the impact of price on market share is relatively low at this stage because of a lack of competitors. As the technology matures so that competing products become more alike and as buyers become aware of more alternatives, market share becomes increasingly responsive to price.

Product Quality:

As buyers gain more information from experience and from word-of-mouth communications, they become more knowledgeable about the relative quality of various products. Thus, market share becomes increasingly responsive to product quality.

Advertising:

Over time, awareness of a brand and its attributes will grow with cumulative exposure to advertisements and saturation levels may ultimately be reached. In any event, diminishing returns will ultimately set in, so market share will become decreasingly responsive to awareness-oriented (as opposed to price-oriented) advertising.

Distribution:

For consumer goods, the sales force usually focuses on obtaining distribution in large-volume stores initially and then on smaller, less important outlets. By maturity, only the marginal outlets are likely to not carry the product. Thus, money spent on additional salespeople, travel expense, or incentives to gain additional distribution will have diminishing returns.

Market share will therefore become decreasingly responsive to distribution expenditures. The present situation in the maturing snack fast foods market in India illustrates the above trends in a big way.

6. Marketing Strategy: Conclusion

Although marketing strategies indicate the general approaches to be used in achieving product objectives, the implementation of these strategies through marketing programmes is the most time-consuming part of marketing management.

Marketing programmes (such as product-development programmes, advertising and sales promotion programmes, and sales and distribution programmes) indicate the specific activities and tactics that will be necessary to implement a strategy.

For instance, if a strategy requires the firm to achieve distributor cooperation, the details of how the sales force will achieve cooperation must be worked out in the sales and distribution programme.

No matter how appropriate a strategy might appear, it will fail if not properly implemented. Consequently, clear statements regarding target markets and marketing strategies are necessary to ensure that the correct programmes and tactics will be developed.

From the foregoing discussions, we can conclude that a marketing strategy serves as the major link between corporate marketing planning and the situation analysis on the one hand and the development of specific programs on the other. Figure 3 portrays this relationship.

Perhaps the most important aspect of this relationship is the fact that marketing strategy should be viewed from a dynamic perspective.