In this article we will discuss about the different types of motivational theories. The theories are: 1. “Maslow’s” Need Hierarchy Theory 2. Herzberg’s Two Factor Theory 3. McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y 4. William Ouchis Theory Z. Learn about:- 1. Motivational Theories in the Workplace 2. Theories of Motivation in Management 3. Types of Motivational Theories 4. Employee Motivation Theories 5. Importance of Employee Motivation 6. Motivational Theories in Organizational Behaviour and 7. Employee Motivation.

Theories of Motivation Studied in Management

Motivational Theory # 1. “Maslow’s” Need Hierarchy Theory: Essential Components and Criticism

Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs theory proposes that people are motivated by multiple needs and that these needs exist in a hierarchical order.

The essential components of the theory may be stated thus:

I. Adult motives are complex. No single motive determines behaviour, rather, a number of motives operate at the same time.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

II. Needs form a hierarchy. Lower level needs must, at least, partly be satisfied before higher level needs emerge. In other words, a higher order need cannot become an active motivating force until the preceding lower order need is essentially satisfied.

III. A satisfied need is not a motivator. A need that is unsatisfied activates seeking behaviour. If a lower level need is satisfied, a higher level need emerges.

IV. Higher level needs can be satisfied in many more ways than the lower level needs.

V. People seek growth. They want to move up the hierarchy of needs. No person is content at the physiological level. Usually people seek the satisfaction of higher order needs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

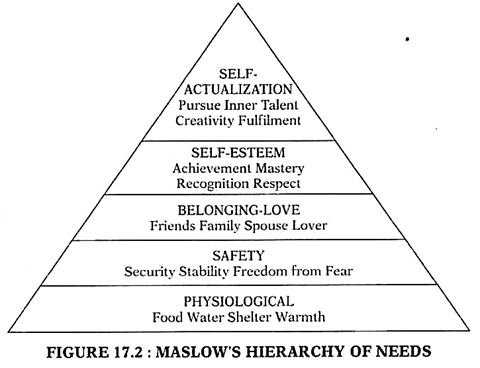

Maslow identified five general types of motivating needs in order of ascendance, as illustrated in Figure 17.2.

I. Physiological Needs:

Physiological needs such as need for food, clothing, shelter etc. are basic needs that preserve human life. They have a tremendous influence on behaviour. They must be met at least partially before other needs are taken up. These take precedence over other needs when thwarted. As pointed out by Maslow, “man lives by bread alone”, when there is no bread.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

They are relatively independent of each other and are essentially finite. An individual demands only a particular amount of these needs. After reasonable gratification, they are no longer demanded and hence, not motivational. They must be met repeatedly within relatively short time periods to remain fulfilled.

II. Safety Needs:

Once physiological needs become relatively well gratified, the safety needs begin to manifest themselves and dominate human behaviour.

These include:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) Protection from physiological dangers (fire, accident);

(ii) Economic security (fringe benefits, health, insurance programmes);

(iii) Desire for an orderly, predictable environment; and

(iv) The desire to know the limits of acceptable behaviour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Maslow stressed emotional as well as physical safety. Thus, these needs are concerned with protection from hazards of life; from danger, deprivation and threat. Safety needs are primarily satisfied through economic behaviour. Organizations can influence these security needs either positively – through pension schemes, insurance plans – or negatively by arousing fears of being fired or laid off. Safety needs, too, are motivational only if they are unsatisfied. They have finite limits.

III. Social/Belongingness/Love Needs:

After the lower order needs are met, the social or love needs become important motivators. Man is a social animal. He wants to belong, to associate, to gain acceptance from associates, to give and receive friendship and affection. People want to meet in order to exchange feelings, thoughts and opinions. Love needs are substantially infinite in nature. People feel the need to be social and mingle, meet and talk to other people. Social needs tend to be stronger for some people than for others and stronger in certain situations.

IV. Esteem Needs:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Esteem needs are two fold in nature- self-esteem and esteem of others. Self-esteem needs include those for self-confidence, achievement, competence, self-respect, knowledge and for independence and freedom. The second group of esteem needs is those that relate to one’s reputation: needs for status, recognition, appreciation and the deserved respect of one’s fellows/associates.

Esteem needs do not become motivators until lower level needs are reasonably satisfied. These needs are insatiable; unlike lower order needs, these needs are rarely satisfied. ‘Satisfaction of esteem needs produces feelings of self-confidence, worth, strength, capability and adequacy, of being useful and necessary in the world’. (Maslow) Thwarting those results in feelings of inferiority, weakness and helplessness. The modern organization offers few opportunities for the satisfaction of these needs of people at lower levels in the hierarchy.

V. Self-Actualization Needs:

These are the needs for realizing one’s own potentialities for continued self-development, for being creative in the broadest sense of that term. “Self-fulfilling people are rare individuals who come close to living up to their full potential for being realistic, accomplishing things, enjoying life, and generally exemplifying classic human virtues.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Self-actualization is the desire to become what one is capable of becoming. A musician must compose music, a poet must write, a general must win battles, a painter must paint, a teacher must teach – if he is to be ultimately happy. What a man CAN be, he MUST be. Self-actualization is a ‘growth’ need.

Self-actualization needs have certain features in common:

i. The specific form that these needs take will vary greatly from person to person. In one person, it may be expressed materially, in still another, aesthetically.

ii. Self-realization is not necessarily a creative urge. It does not mean that one must always create poems, novels, paintings and experiments. In a broad sense, it means creativeness in realizing to the fullest one’s own capabilities; whatever they may be.

iii. The way self-actualization is expressed can change over the life cycle. For example, John Borg, Rod Leaver, ‘Pele’ switching over to coaching after excelling in their respective fields.

iv. These needs are continuously motivational, for example: scaling mountains, winning titles in fields like tennis, cricket, hockey, etc. The need for self-realization is quite distinctive and does not end in satisfaction in the usual sense.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

v. These needs are psychological in nature and are substantially infinite.

vi. The conditions of modern life give only limited opportunity for these needs to obtain expression.

Maslow’s theory has been criticized on the following grounds:

a. Theoretical Difficulties:

The need hierarchy theory is almost a non-testable theory. It defies empirical testing, and it is difficult to interpret and operationalize its concepts.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

b. Research Methodology:

Maslow’s model is based on a relatively small sample of subjects. It is a clinically derived theory and its unit of analysis is the individual.

c. Superfluous Classification Scheme:

The need classification scheme is somewhat artificial and arbitrary. Needs cannot be classified into neat watertight compartments – a neat 5-step hierarchy. The model is based more on wishes of what man should be than what he actually is.

d. Chain of Causation in the Hierarchy:

There is no definite evidence to show that once a need has been gratified, its strength diminishes. It is also doubtful whether gratification of one need automatically activates the next need in the hierarchy. The chain of causation may not always run from stimulus to individual needs to behaviour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Further, various levels in the hierarchy imply that lower level needs must be gratified before a concern for higher level needs develop. In a real situation, however, human behaviour is probably a compromise of various needs acting on us simultaneously. The same need will not lead to the same response in all individuals. Also, some outcomes may satisfy more than one need.

e. Needs Crucial Determinants of Behaviour:

The assumption that needs are the crucial determinants of behaviour is open to doubt. Behaviour is influenced by innumerable factors—not necessarily by needs alone. The relative mix of needs may change over time. During 1940s and 1950s workers wanted a secure work place, in 1960s and 1970s they wanted interesting work, after the 1980s workers wanted freedom to think and act independently. So presenting a theory in terms of a static as well as questionable set of compartmentalized needs does not reveal a clear picture. Owing to these limitations, the need priority model provides, at the best, an incomplete and partial explanation of behaviour.

f. Individual Differences:

Individuals differ in the relative intensity of their various needs. Some individuals are strongly influenced by love needs despite having a flourishing social life and satisfying family life; some individuals have great and continued need for security despite continued employment with enormous fringe benefits.

Young workers have greater esteem and self-fulfillment deficiencies than the older workers. Culturally disadvantaged employees may feel stronger deprivation of biological and safety needs, whereas culturally advantaged employees prefer satisfaction of higher order needs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Educated employees place a premium on challenging tasks. In comparison, less educated employees prefer routine and standardized jobs. The picture will be very confusing if we apply the theory in different countries with cultural, religious differences. In one case, black managers had a greater lack of need fulfillment than their black counterparts in almost every category. Surveys in Japan and Continental European countries show that the model does not apply to the managers.

Cultural, religious, environmental influences play a major role in determining the need priority in various countries. Thus, the theory hardly reckons with a whole set of factors affecting individual need structure—race, position in authority structure, and culture, etc. Few (if any) data support the idea that all people are capable of activating all levels of the need structure. Moreover, managers do not have substantial amounts of time for a leisurely diagnosis of where every employee is positioned in the Maslow’s need priority model.

Maslow’s need priority model, however, should not be viewed as a panacea for explaining all kinds of motivational problems. It only offers a simple answer as to why people act the way they do. The need priority model is useful because of its rich and comprehensive view of needs. The theory is still relevant because needs – no matter how they are classified – are important for understanding behaviour.

It is simple to understand that it has a commonsense appeal for managers. It has been widely accepted—often uncritically, because of its immense intuitive appeal only. It has survived, obviously more because of its aesthetics than because of its scientific validity.

Motivational Theory # 2. Herzberg’s Two Factor Theory: Maintenance Factors and Comparison

For several years, managers had been wondering why their fancy personnel policies and fringe benefits were not increasing employee motivation on the job. To answer this, Frederick Herzberg of Case-Western Reserve University provided an interesting extension of Maslow’s Need Hierarchy theory and developed a specific content theory of work motivation. It is also called the ‘Dual Factor Theory’ and the ‘Motivation-Hygiene Theory’. The theory originally was derived by analysing “critical incidents” written by 200 engineers and accountants in nine different companies in Pittsburgh Area, USA.

Herzberg and his associates conducted extensive interviews with the professional subjects in the study and asked them what they liked or disliked about their work. The research approach was simplistic and built around the question—”Think of a time when you felt exceptionally good or exceptionally bad about your job, either your present job or other you have had”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This approach has been repeated many times with a variety of job holders in various countries. The results indicated that when people talked about feeling good or satisfied they mentioned features intrinsic to the job and when people talked about feeling dissatisfied with the job they talked about factors extrinsic to the job. Herzberg called these Motivation and Maintenance factors, respectively.

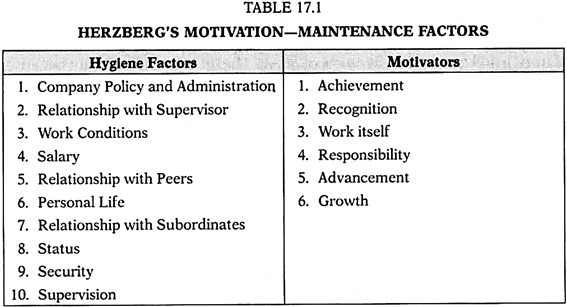

Hygiene Factors (Maintenance Factors):

Hygiene factors represent the need to avoid pain in the environment. They are not an intrinsic part of a job, but they are related to the conditions under which a job is performed. They are associated with negative feelings. They are environment-related factors – hygiene. They must be viewed as preventive measures that remove sources of dissatisfaction from the environment. Like physical hygiene, they do not lead to growth but only prevent deterioration.

Maintaining a hygienic work environment will not improve motivation any more than garbage disposal or water purification. Mr. Fictitious, who is in excellent health, will not become any healthier by eating food but if he does not eat food he may become sick and die. Hygiene factors produce no growth in worker output, but they prevent loss in performance caused by work restriction.

Motivators:

Motivators are associated with positive feelings of employees about the job. They are related to the content of the job. They make people satisfied with their job. If managers wish to increase motivation and performance above the average level, they must enrich the work and increase a person’s freedom on the job. Motivators are necessary to keep job satisfaction and job performance high. On the other hand, if they are not present they do not prove highly satisfying.

The implications of the two factor theory for managers are quite clear. Providing hygiene factors will eliminate employee satisfaction but will not motivate employees to high achievement levels on the other hand, recognition, challenge, growth opportunities are powerful motivators and will promote high satisfaction and performance. The manager’s role is to eliminate dissatisfies-that is, to provide hygiene factors sufficient to meet basic needs – and then use motivators to meet higher – order needs and propel employees toward greater achievement and satisfaction.

Departure from the Traditional View [D]:

Traditionally, job satisfaction and dissatisfaction were viewed as opposite ends of a single continuum, when certain things are present on a job—good pay, opportunity for growth, healthy working environment—the employee will be satisfied. When they are absent, he is dissatisfied. The absence of dissatisfaction is satisfaction.

Herzberg’s findings indicate that dissatisfaction is not simply the opposite of satisfaction or motivation. One can feel no dissatisfaction and yet not be satisfied. Satisfaction and dissatisfaction appear to be somewhat independent. They are not viewed as symmetrical items on a single scale, rather, they are viewed as attributes of different scales. The factors that cause dissatisfaction are different from those that result in satisfaction. Satisfaction is affected by motivators and dissatisfaction by hygiene factors.

Comparison of Maslow and Herzberg Models:

One of the main reasons for the popularity of the Two Factor Theory is that it is compatible with Maslow’s Need Hierarchy. Maslow and Herzberg—both tend to oversimplify the motivational process, emphasize the same set of relationships and deal with the same problem. Maslow formulated the theory in terms of needs and Herzberg in terms of goals or rewards. However, Herzberg attempted to refine and hedge on the need hierarchy and cast a new light on the content of work motivation.

Herzberg recommended the use of hygiene factors to help people to attain their lower level needs. Motivators are recommended to meet upper level needs. Whereas Maslow’s theory implies a hierarchical (sequential) arrangement with greater force from unfulfilled needs and movement through the hierarchy in an ordered or ‘cascade’ fashion. According to Maslow any unsatisfied need, whether of lower order or higher order, will motivate individuals.

Both models show marked similarities. As a result, the juxtaposition of the two models makes logical sense and is interesting to observe.

The Hygiene factors are roughly equivalent to Maslow’s lower order needs and the motivational factors are somewhat equivalent to higher order needs. Both models assume that specific needs energize behaviour.

Although there are marked similarities in the two models many differences exist unfortunately neither model provides an appropriate link between organizational goals and individual need satisfaction. Both fail to handle the question of individual differences in motivation.

Differences in Maslow’s and Herzberg’s Motivation Theories:

Maslow’s Model:

1. Type of theory- Descriptive

2. Satisfaction-performance relationship- Unsatisfied needs energize behaviour and cause performance.

3. Effect of need satisfaction on performance- A satisfied need is not a motivator

4. Need order- Hierarchy of needs

5. Effect of pay- Pay is a motivator if it satisfies needs.

6. Effect of needs- All needs are motivators at various points of time

7. View of motivation – Macro view—deals with all aspects of existence

8. Worker level – Relevant for all workers

Herzberg’s Model:

1. Type of theory- Prescriptive

2. Satisfaction-performance relationship- Needs cause performance

3. Effect of need satisfaction on performance- Only motivators can stimulate superior performance

4. Need order- No hierarchy

5. Effect of pay- Pay is not a motivator

6. Effect of needs- Only some needs are motivators

7. View of motivation – Micro view deals primarily with work related motivation

8. Worker level – Probably more relevant for white collar and professional workers

Limitations and Criticism:

Herzberg’s theory has been subjected to several troubling criticisms. Like Maslow’s model, Herzberg’s model has been as controversial as it has been influential.

1. Research Methodology:

(i) Herzberg is shackled to his method. His model is method-bound. When researchers did not use the critical incident method, they obtained different results;

(ii) Actually, the theory is limited by the ‘critical incident’ method used to obtain information. The subject stated only extremely satisfying and dissatisfying job experiences. People tend to tell the interviewer what they think the individual would like to hear. So results obtained under the method may be a product of people’s defensiveness than a correct revelation of objective sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction;

(iii) The method is fraught with procedural deficiencies also. The analysis of the responses derived from his approach is highly subjective, sometimes the researchers had to interpret the responses;

(iv) Also, using the critical incident method may cause people to recall only the most recent experiences. The ‘recovery of events’ bias is embedded in the methodology.

2. Empirical Validity:

King, noted that the model itself has fine different ‘ interpretations and that the available research evidence is not consistent with any of these interpretations. The theory is most applicable to knowledge workers—managers, accountants, engineers, etc. Most studies have shown that when the employees were professional in nature, the theory is applicable. Studies of manual workers are less supportive of the theory. Herzberg’s study, hence, is not representative of the workforce, in general.

3. Assumptions:

(i) The assumption that the two sets of factors operate primarily in one direction is also not accurate. Critics questioned the mutual exclusiveness of the dimensions. In some cases ‘maintenance factors’ were found to be viewed as motivators by blue-collar employees. In one study, it was found that hygiene factors were as useful in motivating employees as were the motivators. A clear distinction between factors that lead to satisfaction and those that lead to dissatisfaction cannot be maintained.

Herzberg’s model propagates a myth that hygiene’s are enough to motivate workers and motivators must be pressed into service while dealing with managers. This dichotomy is unfortunate because it perpetuates a chasm between sub-systems of organizations that really should be integrated for effective performance. All are managers; all are workers.

(ii) The theory focuses too much attention on ‘satisfaction’ or ‘dissatisfaction’ rather than on the performance level of the individual. Much importance is not given to such factors like status, pay, interpersonal relationships, which are generally held as important determinants of satisfaction.

Further, researchers have questioned the equation between satisfaction and motivation and also attacked the assumption that satisfaction leads to superior performance. Actually, motivation, satisfaction and performance are all separate variables and relate in different ways from what was assumed by Herzberg.

Despite these criticisms, Herzberg’s two factor theory has made a significant contribution toward improving manager’s basic understanding of human behaviour. He advanced a theory that was simple to grasp, based on some empirical data, and significantly offered specific action recommendations for managers to improve employee motivation levels. He drew the attention of managers to the importance of job content factors in work motivation which had been neglected previously.

Motivational Theory # 3. McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y: With Assumptions

Douglas McGregor proposed two distinct sets of assumptions about what motivates people-one basically negative, labelled Theory X; and the other, basically positive, labelled Theory Y.

Assumptions of Theory X and Theory Y:

Theory X Assumptions:

i. Employees inherently dislike work and will try to avoid it.

ii. Since employees dislike work, they must be coerced, controlled and threatened with punishment to achieve goals.

iii. Employees will shirk responsibilities and seek formal direction, whenever possible.

iv. Most employees want security above- all in their work and display little ambition.

Theory Y Assumptions:

i. Employees can view work as being as natural as rest or play.

ii. People will exercise self-direction and self-control if they are committed to the objectives.

iii. Under proper conditions, employees do not avoid responsibility.

iv. People want security but also have other needs such as self-actualization and esteem.

Theory X:

Theory X contends that people have an inherent dislike of work and will avoid it whenever possible. Most people, being lazy, prefer to be directed, want to avoid responsibility and are relatively less ambitious. They must be coerced, controlled, directed or even threatened with punishment to get them to work towards organizational goals.

External control is clearly appropriate for dealing with such unreliable, irresponsible and immature people. Managers have to be strict and authoritarian if subordinates are to accomplish anything. Theory X thus, assumes that lower-order needs (Maslow) dominate human behaviour. Money, fringe benefits and threats of punishment play a great role in putting people on the right track under this classification scheme.

Theory Y presents a much more optimistic view of human nature. It assumes that people are not, by nature, lazy and unreliable. They will direct themselves towards objectives if their achievements are rewarded. Most people have the capacity to accept, even to seek responsibility as well as to apply imagination, ingenuity, and creativity to organizational problems. If the organizational climate is conducive, people are eager to work; and they derive a great deal of satisfaction from work, and they are capable of doing a good job.

Unfortunately, the present industrial life does not allow the employees to exploit their potential fully. Managers, therefore, have to create opportunities, remove obstacles and encourage people to contribute their best. Theory Y, thus, assumes that higher-order needs (Maslow) dominate human behaviour. In order to motivate people fully, McGregor proposed such ideas as participation in decision making, responsible and challenging jobs and good group relations in the workplace.

McGregor seems to have played a “very disturbing little joke”, unwittingly, by drawing a sharp line of demarcation, between the two distinct perspectives of administrative action. One is equated with tradition and the other is identified with change. One is labeled as autocratic, control-centered and the other is glamorized as the epitome of democratic governance.

The impression that one might get from the discussion is that managers who accept Theory X assumptions about human nature exhibit a built-in affinity for carrot and stick policies while Theory Y managers exhibit a built-in devotion to participative, behaviour-centred policies.

According to theory X, man is weak, sick and incapable of looking after himself. He is full of fears, anxieties, neuroses, and inhibitions. Essentially, he does not want to achieve but wants to fail. He therefore, wants to be controlled. More dangerously, it does not assume that people are lazy and resist work, but it assumes that the manager is healthy while everybody else is sick.

It assumes that the manager is strong while everybody else is weak. It assumes that the manager knows while everybody else is ignorant. It assumes that the manager is right, where everybody else is stupid. These are nothing but “assumptions of foolish arrogance” (Drucker).

Now let us turn our attention to the so-called democratic theory based on the needs of man, addressed to his managerial brethren by McGregor in a persuasive, yet, forceful manner. Theory Y gives us an impression that everyone is mature, independent and self-motivated. Most of the writers, no wonder, glamorized the vision of a so-called administrative democracy (simply because it is good!).

The rationale behind this observation is- Whatever is autocratic is ‘bad’ by definition. This may not hold good always. Sometimes, managers may have theory Y assumptions about human nature, but they may find it necessary to behave in a very directive, controlling manner with some people in the short- run to help them ‘grow’ up in a developmental sense, until they are theory ‘Y’ people.

One interesting question can be posed in this connection: Is it possible for a theory X person to become a Theory Y person? Probably yes, but only through “a fairly significant growth or development experiences over a period of time”. Theory X places exclusive reliance on external control of human behaviour while theory Y relies heavily on self-control and self-regulation. “This difference is the difference between treating people as children and treating them as mature adults. After generations of the former, we cannot expect to shift to the latter overnight”. (McGregor)

Motivational Theory # 4. William Ouchis Theory Z:

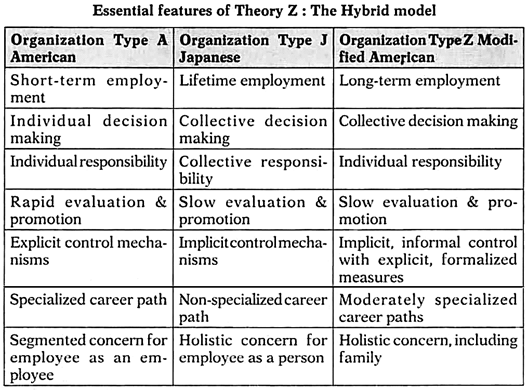

William Ouchi, after making a comparative study of American and Japanese management practices, proposed Theory Z in early 80s. In the 80s the quality of products manufactured by US companies was so bad that when a Japanese company ordered an American car, they had to disassemble those cars, remove the defects and rebuild them to meet Japanese standards.

Rapid promotions, quick decisions, vertical progressions, pin-pointed responsibility, control mechanisms characterized American management thinking. The Japanese on the other hand believed in collective responsibility, group decisions, slower promotions, life time employment, etc. The popular feeling was that Japan was miles ahead of other nations—in terms of quality, productivity etc.—due to these morale boosting measures.

Differences in Managerial Thinking and Philosophy America vs. Japan:

The different assumptions between American and Japanese management may be presented thus:

a. Job Security:

The Japanese Theory Z approach believes that people are a far too valuable resource to be lost when the economy has a downturn. In a recession, the Japanese don’t fire people, they will reduce their hours until things pick up. By contrast, when a US company is in trouble, they waste no time laying people off and as a result lose all the knowledge, skills and expertise that go with them.

b. Trust:

The Japanese feel that you should never give people a reason to distrust you. Loyalty is expected of all employees. In American companies, distrust and suspicion are endemic. If a person or supplier is not delivering, the company will go elsewhere for a better deal.

c. Decision-Taking:

In Japanese companies, everyone gets involved in the decision-taking process as part of their commitment to the organisation. As a result, the process is slow. In the US, decision-taking is the responsibility of the few and so is quick.

d. Teamwork:

In Japan, organisational success is viewed as the result of team effort, so it is illogical to reward individuals. In the US rewards are based on effort and overall performance.

e. Motivation and Target-Setting:

The Japanese corporation rarely sets targets for individuals- as a way of motivating them. They believe that individual motivation comes from others in the team. Consequently, a Japanese employee would rarely get the first performance evaluation report during the formative years. It will take many more years, before he gets the first promotion. By contrast, the American corporation believes that the role of management is to set their subordinates targets and ensure that these are met, using evaluation and promotion as incentives and rewards.

Ouchi recognized these differences and decided to develop a hybrid, integrative model, containing the best of both worlds. It takes into account the strengths of Japanese management (social cohesion, job security, concern for employees) as well as American management (speedy decision making, risk taking skills, individual autonomy, innovation and creativity) and proposes a ‘mixed US’ Japanese management system for modern organizations.

Theory Z is an approach to management based upon a combination of American and Japanese management philosophies and characterized by, among other things, long-term job security, consensual decision-making, slow evaluation and promotion procedures, and individual responsibility within a group context.

The mixed/hybrid system has the following characteristics:

I. Trust:

Trust and openness are the building blocks of Theory Z. The organisation must work toward trust, integrity and openness. One of the favourite quotes in Japan is that ‘you should never give people reason to distrust you’. In such an atmosphere of mutual respect and admiration, the chances of conflict are reduced to the minimum. Trust, according to Ouchi, means trust between employees, supervisors, work groups, management, unions and government.

In Japan it is not strange to find managers working side by side with their employees. Such close working relations help in developing open, friendly relations between labour and management.

II. Organisation-Employee Relationship:

Theory Z argues for strong linkages between employees and the organisation-

a. Long term employment is one such measure that strengthens the relations between workers and management.

b. When faced with a situation of lay off, management should not show the door to unwanted people. Instead, it could cut down the working hours or ask stakeholders to bear with the temporary losses.

c. To encourage stable employment relationship, promotions could be slowed down. In fact, in a Japanese organisation a person is normally not promoted until he has served ten years with the company.

d. Instead of vertical progression, horizontal progressions may be laid down clearly so that employees are aware of what they can achieve and to what extent they can grow within the organisation over a period of time.

e. To compensate slower promotion companies can offer incentive to people who stay on. Such people can be asked to work closely with superiors on important projects/assignments. This way the company can make those employees think that their services are really wanted.

f. Employees may be asked to learn every aspect of work in every department. Through such rotating jobs, employees become versatile and remain useful almost everywhere.

III. Employee Participation:

Participation here does not mean that employees must participate in all organizational decisions. There can be situations where management may arrive at decisions without consulting employees; decisions where employees are invited to suggest but the final green signal is given by management. But all decisions where employees are affected must be subjected to a participative exercise; where employees and management sit together, exchange views, take down notes and arrive at decisions jointly. The basic objective of employee involvement must be to give recognition to their suggestions, problems and ideas in a genuine manner.

IV. Structureless Organization:

Ouchi proposed a structureless organization run not on the basis of formal relationships, specialisation of positions and tasks but on the basis of teamwork and understanding. He has given the example of a basketball team which plays together, solves all problems and gets results without a formal structure. Likewise in organisations also the emphasis must be on teamwork and cooperation, on sharing of information, resources and plans at various levels without any friction.

To promote a ‘systems thinking among employees, they must be asked to take turns in various departments at various levels. Job rotation enables them to learn how work is processed at various levels; how their work affects others or is affected by others, it also makes the employees realize the meaning of words such as ‘reconciliation,’ ‘adjustment,’ ‘give and take’ in the organizational context.

V. Holistic Concern for Employees:

To obtain commitment from employees, leaders must be prepared to invest their time and energies in developing employee skills, in sharing their ideas openly and frankly, in breaking the class barriers, in creating opportunities for employees to realize their potential. The basic objective must be to work cooperatively, willingly and enthusiastically. The attempt must be to create a healthy work climate where employees do not see any conflict between their personal goals and organizational goals.

Implications of Theory Z:

Indian companies have started experimenting with these ideas in recent times, notably in companies like Maruti Udyog Limited, BHEL, by designing the work place on the Japanese pattern by having a common canteen, a common uniform both for officers and workers, etc., Other ideas of Ouchi such as lifelong employment, imbibing a common work culture, participative decisions, structure less organisations, owners bearing the temporary losses in order to provide a cushion for employees— may be difficult to find any meaningful expression on the Indian soil because of several complicating problems.

The differences in culture (north Indian and south Indian), language (with over a dozen officially recognized ones), caste (forward, backward, scheduled caste, scheduled tribe, economically backward), religion (Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Jain, Christian, etc.), often come in the way of transforming the seemingly appealing Western rhetoric into concrete action plans.

Some of the inherent weaknesses in Ouchi’s management philosophy might be listed thus:

1. In a competitive scenario, it is not possible to offer life time employment or employment on a long term basis to job seekers—howsoever talented they might be. This has happened in Japan too where companies had to cut down costs as a survival measure and compelled to show the door to employees. When the organisation is hit by a down turn, for a fairly long period, it cannot remain wedded to its people on a permanent basis

2. Participation may not always encourage people to give their best. Its psychic effects are open to doubt. In fact the participative culture may itself become a bone of contention over a period of time. Listening to everybody on all matters goes against the principles that govern quick, efficient decisions.

3. Long lasting relationships between superiors and subordinates overcoming the caste, region, religion feelings is not an easy job.

4. Structure less organisations suggested by Ouchi may not always produce results. This may produce chaos and confusion among ranks, if people are not used to such culture. It may be difficult to pin point responsibility on any one in a structure less organisation.

5. Most often stakeholders may not like a situation of swallowing losses when hit by a downturn in economic activities. They may not like to keep unwanted hands for longer periods, as a goodwill gesture to please unions or workers.

6. The principles of Japanese Management do not seem to find universal acceptance. The very fact that most Japanese companies have not been doing very well during the last couple of years, bears ample testimony to this fact. Management, as a subject, is evolving.

7. The theories of motivation, likewise, require revision, modification, and at times, radical surgery. At times, they seem to produce outstanding results. At other times, they do not seem to work at all.

The book In Search of Excellence listed excellent organizations based on some well-known principles and practices of management. The authors, Peters and Waterman had to rewrite the story again (and even admitted that they faked the data) when many of those excellent organizations—Xerox, Wang Labs, NCR—turned negative performance for painfully longer periods of time.