A project report on motivation of employees in an organisation. This report will help you to learn about:- 1. Meaning of Motivation 2. Nature of Motivation 3. Importance of Motivation 4. Purposes 5. Need 6. Motivation, Ability and Performance 7. Models 8. Theories 9. Role of Money in Motivation Theory and Other Details.

Contents:

- Project Report on the Meaning of Motivation

- Project Report on the Nature of Motivation

- Project Report on the Importance of Motivation

- Project Report on the Purposes of Motivation

- Project Report on the Need for Positive Motivation

- Project Report on Motivation, Ability and Performance

- Project Report on the Motivation Models

- Project Report on the Theories of Motivation

- Project Report on the Role of Money in Motivation Theory

- Project Report on How Occupational Level Affects Motivation?

- Project Report on Managing Motivation

- Project Report on the Integration and Application of Motivation Theories

Project Report # 1. Meaning of Motivation:

Many firms proudly point to their productivity increases and claim that the increases are due to y employees working smarter, not harder. But in many other firms, managements fail to reward employees for working either harder or smarter.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Many powerful tools lie within management’s control, but the tools have to be applied consistently and within the framework of an overall strategy for performance improvement.

Such a strategy must coordinate the various elements of human resource management into a unified programme whose focus is to enhance employees’ motivation to work; too often, managers have sacrificed equitable treatment for equality of treatment. To see how such a strategy might be applied in practice, let’s examine three popular categories of motivation theories.

Motivation is a subject about which there, is hardly any misunderstanding and about the importance of motivation there is hardly any controversy.

The challenge facing a modern manager is how to motivate employees to display behaviour consistent with organisational goals or objectives such as reducing costs, increasing revenues and satisfying customers. Motivation arises from within employees, and motivational factors differ for each individual within an organisation.

Motivation Defined:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The continual challenges faced by management is the motivation of employees. When managers analyze their work people, they always discover that some people invariably out-perform others of equal skill, efficiency and ability.

A close scrutiny often reveals that in some situations a person with outstanding talents is consistently out-performed by someone having lesser talent. The proximate cause seems to be that the latter employees voluntarily put more effort and try harder in order to accomplish their goals.

These hard workers are often described by their bosses as ‘motivated workers’. To discover why workers behave in that way we have to look at the person and his needs.

Motivation is defined as the activation and direction of energy. It refers to inducing a person or a group of people, each with his (her) own distinctive needs and personality, to work to achieve the organisation’s objectives, while also working to achieve his (her) own objectives.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Echoing the above basic definition Craig Pinder has suggested the following comprehensive definition of work motivation:

Work motivation is a set of energetic forces that originate both within as well as beyond an individual’s being, to initiate work-related behaviour, and to determine its form, direction, intensity, and duration.

Project Report #

2. Nature of Motivation:

Employee motivation is no doubt a major concern of most managers. The pertinent question here is: how can employees be induced to serve organisational goals as part of their own goal sets and to work hard to achieve them? The answer is through proper motivation. Motivation is “an interactive process affecting the inner needs or drives that energise, channel and maintain behaviour”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

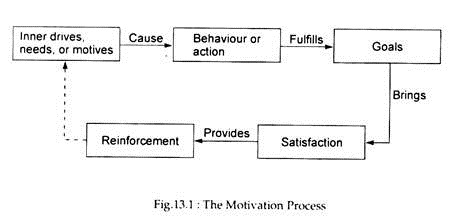

The process of motivation is illustrated in Fig. 13.1. The process starts with inner drives and needs that motivate (cause to move) the individual to work toward certain goals, which the individual has chosen in the belief that they will satisfy inner drives and needs. Once these goals are attained, the individual consciously or unconsciously judges whether the effort has been worthwhile.

To the extent that the individual perceives the effort as rewarding, the behaviour of making the effort is reinforced and the individual will continue or repeat the same kind of behaviour. Industrial psychologists have pointed out that reinforcement, or what happens as a result of behaviour, affects other needs and drives of employees as the whole process is repeated; hence its cyclical nature, as shown in Fig.13.1

Project Report #

3. Importance of Motivation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

No doubt employee motivation is of crucial concern to managers, mainly because of the role that employee motivation plays in performance.

The Hawthorne studies started an investigation into the nature of people and their performance at work. The same exercise has been carried out further by modern researchers in their search for understanding the complexities of human nature.

Since people are the most important resource of an organisation their behaviour has to be studied, analysed and interpreted properly. In other words, the need is to study people’s behaviour along with their jobs, their organisations and various other influences.

Behavioural process are of paramount importance in an organisation. Without organisational people and the behaviour they display, organisations could never come into existence. Among the behaviour processes, motivation is generally treated as one of strategic importance.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is because lack of motivation results in such negative consequences as ineffective performance and high levels of absenteeism and turnover. In fact, the real answer to the problems boredom and dissatisfaction of workers on the job is motivation. This explains why result-oriented managers lay heavy stress on motivation.

Basically, performance is determined by three things: ability, motivation and environment. To be able to perform effectively, one must know how to do the job (ability), must be desirous of doing the job (motivation) and must have the proper setting, materials and tools to do the job (environment). If any one of these three factors is deficient or missing, effective performance is not possible.

A manager can have the most highly qualified subordinate in the world and provide him (her) with the best tools and equipment unless the subordinate is motivated to perform. With proper motivation all employees would do the bare minimum necessary to earn his living and keep his job intact and nothing beyond that.

The importance of motivation is illustrated in Fig.13.1. It shows the influence of motivation on performance. A manager has two ways to improve performance: training and motivation. Assume that the training is combined with a low level of motivation, only a very small increase in performance occurs (A). When training is combined with a high level of motivation, performance increases dramatically (B).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Andrew Grove, president of a highly successful U.S. company, has brought into focus an important point: while ability is positively correlated with performance, the correlation is, at best, imperfect. Organisational members with a high level of motivation are usually much more productive than those with a low level of motivation.

As Fig.13.2 above shows, a manager is left with two options to improve performance: training and motivation. Let us assume that the training of subordinates is equal. But when training is supported by a low level of motivation, only a marginal increase in performance occurs (A). On the contrary, when training is combined with a high level of motivation, performance improves dramatically (B).

Our major concern is to examine the concept of motivation and present alternative theories of motivation to assist managers in creating a supportive climate for performance.

Project Report # 4. Purposes of Motivation:

People mainly look for money when deciding to join an organisation. It is often said that learning is for earning. But certain non-monetary factors such as promotion possibilities, working conditions, and the opportunity to do creative work become important considerations to those who are already gainfully employed. Safety, security, and current and terminal benefits become more important for senior and older employees who are on the verge of retirement.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, if a person has a steady job, with a ‘satisfactory’ income, he may not consider money — in the form of wage and compensation — as important as challenging and regarding work, but, if an individual is seeking employment or does not have material benefits, or if he perceives his financial position to be declining or threatened, he may regard money — in the form of benefits or security — as the greatest motivator.

Thus motivation is highly individualistic; it is the essence of human behaviour. However, different people, having different backgrounds, needs and aspirations, probably rank the items differently. But certain underlying principles and theories of motivation enable managers to better understand and predict people’s responses to performing their tasks, despite the uniqueness (commonalty) of human beings.

Three major purposes of managerial motivation are enumerated below:

1. To encourage potential employees to join the organisation.

2. To stimulate present employees to produce or perform more effectively.

3. To encourage present employees to remain with the organisation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Each of these requires different approaches, tactics and incentives.

Project Report #

5. Need for Positive Motivation:

The problem of motivation is complex because managers continually generate either positive or negative responses from employees. Production increases when managers obtain a positive response; it ceases to increase (or even falls) when the response is negative. Thus the essence of management is motivation. So the pertinent question here is what type of motivation managers can use most effectively to stimulate improved performance.

Research on work behaviour has revealed that many workers have experienced boredom, dissatisfaction and alienation. The adverse consequences of all these are: poor quality of goods and services, high employee turnover and absenteeism, wasted time and materials that are lost in the production process, and the consequent high costs, prices and loss of potential profit.

Motivation is thus required to overcome the hazard of job burnout, which is physical or mental depletion significantly below one’s capable level of performance. In fact, it is the root cause of absenteeism, alienation and work place antagonisms.

To tackle these problems, managers have to design job with periods of rest from responsibility, to rotate employees into less pressured positions, or to otherwise motivate them to operate more effectively. Thus motivation is needed because of employee’s increasing awareness of their individual rights, which may lead to negative attitudes toward the job.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally, positive motivation has a direct impact on productivity and profitability. Recent years have witnessed a decline of productivity of the U.S. labour force and an increase in that of the Japanese work force.

Project Report # 6. Motivation, Ability and Performance:

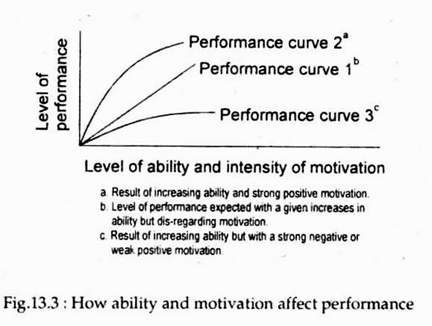

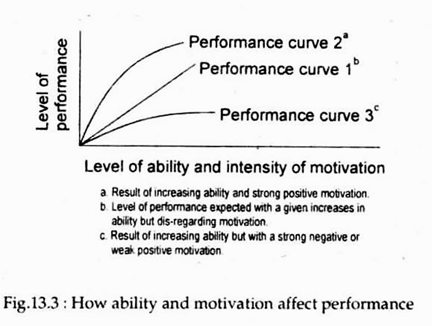

We have already examined the influence of motivation on performance. So long we assumed that individuals are alike in skill, ability and efficiency. Thus their performance differs mainly due to differences in motivation. Now we shall modify our conclusion slightly and observe that motivation and ability conjointly affect performance. This point is illustrated in Fig.13.3.

The performance curve 1 shows that employees output varies directly with increases in their abilities. In other words, this is the performance curve if productivity were based on ability alone. This curve shows a direct and proportional relation between the two: performance should increase directly and proportionately as ability increases.

But employees enjoy some degree of discretion — they have the freedom of choice to perform effectively, ineffectively, or not at all. Thus motivation is important to increase output. Thus the employees’ actual performance curve is also related to the type and extent of motivation involved.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The performance curve 2 shows that the employees’ output (productivity) increases at an increasing rate when there is increasing ability and/or strong positive motivation. Finally, the performance level will continue to be low when there is strong negative or weak positive motivation, regardless of changes in ability.

Thus the conclusion that emerges from our discussion so far is that employee performance is a function of ability times motivation or, to show the relation symbolically,

P = f (A x M x R)

where P stands for performance; f, function; A, ability; M, motivation; and R, role perception. Thus output is affected not only by ability and motivation, but also by the way people view their role in the organisation.

Factors Affecting Ability and Motivation:

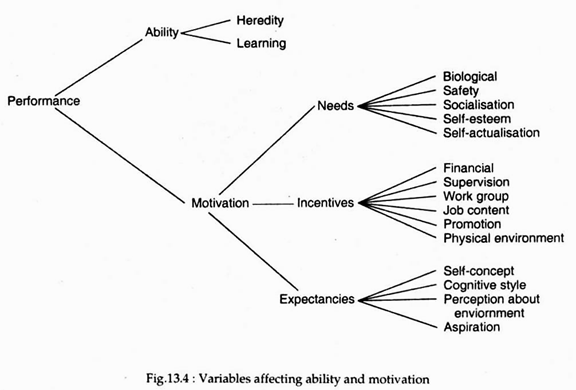

The performance equation and derived curves are oversimplified. They do not reflect the real world. In practice a person’s ability and motivation are the result of various other factors all of which cannot be measured or quantified.

Motivation occurs through the interaction of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards with employee needs, as modified by the employees’ expectations. That motivation is very complex is seen from the relationship among these variables (as depicted in Fig. 13.4). Most of these are beyond the control of the manager or the area of his influence. But this does not disprove the fact that managers can and do motive employees toward improved performance over time.

Results of Effective Motivation:

Motivation is no doubt the best potential source of increased productivity and profitability. But it does not necessarily imply a greater expenditure of energy on the part of the worker. Rather, it implies that the abilities of employees will be used more effectively with the same or even less — expenditure on effort. This, in its turn, is likely to lead to greater job satisfaction.

Project Report # 7. Motivation Models:

A. The Basic Motivation Model:

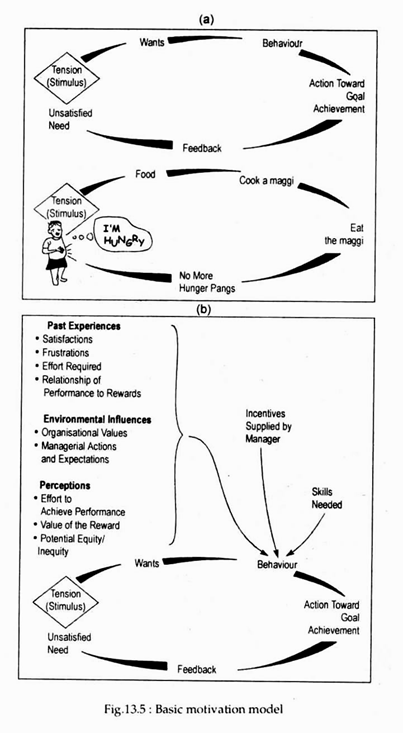

The needs of a person provide the foundation of motivational model. Needs refer to the deficiencies a person is experiencing at a particular time. The needs may be physiological — such as need for food, air, water, sunshine, etc., or psychological — affiliation with others or self-esteem. The needs give rise to a stimulus that results in wants. The person then attempts to develop a behaviour or set of behaviours to achieve the goal.

Fig. 13.4(a) illustrates the relationship of needs to performance. It gives a real-life example: a person feels hungry (need); realising this generates a want (food); he chooses to cook Maggi(behaviour) which he (she) will eat (action) to achieve (the goal). Thus his need is satisfied and afterwards he does not feel hungry (feedback).

But this is not the whole truth. It is because mere identification of the foundation for motivation is not enough. We have to analyse various influences on the motivated behaviour of a person: why did the person choose Maggi rather than rice? Why did he cook his instead of buying it? Has the behaviour been used in the past? If so, did it satisfy his want (need)? Did the person still feel hungry?

We may now adopt an alternative but more integrative approach, as presented in Fig.13.5(a) and 13.5(b).

B. Integrated Motivation Model:

Wants are unlimited and unsatisfied needs stimulate wants.

As the person has to choose a behaviour to satisfy the need, he (she) has to consider and evaluate several factors:

1. Past Experiences:

An individual’s all the past experiences with the situation at hand enter, into the motivation model. These may include experiences with a particular behaviour, satisfactions derived and frustrations, effort required and the relationship of performance to rewards.

2. Environmental Influences:

The person’s behaviour choices are also affected by the environment, which refers to the totality of forces which are external to and beyond his control (such as the values of the organisation, as well as the expectations and actions of the manager).

3. Perceptions:

An individual is also largely influenced by his (her) perceptions of the reward, and the value in relation to what peers have received for the same effort.

Other variables included in the model are skills and incentives (positive and negative results). Skills refer to the person’s capabilities (usually the result of training) for performing, while incentives (after referred to as rewards) are an external stimulates that induce one to attempt to do something or to achieve something. In short, incentives are factors created by management to encourage workers to perform a task.

Let us go back to the process described above: unsatisfied needs stimulate wants. While considering behaviour to satisfy the wants, the person is evaluating the rewards or punishments associated with the performance (incentives) his (her) abilities to take action (skill), and past experiences, environmental influences, and perceptions.

This leads us to a generalised definition of motivation:

“The interaction of a person’s internalised needs and external influences which determines behaviour design to achieve a goal.”

Human Behaviour affects Motivation- According to some writers management can never become a science because managers have to deal with:

(1) Human behaviour that often seems unpredictable and irrational and

(2) Human beings, who mostly act from emotions rather than with reason.

There is no denying the fact that people do at times behave emotionally. But we still continue to assume that most human behaviour is rational and largely predictable.

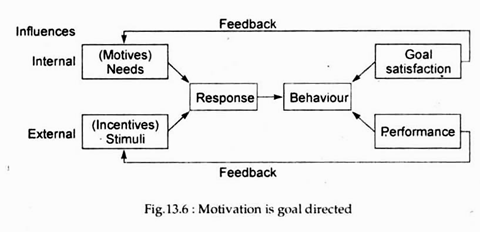

We make two basic assumptions about human behaviour at this stage. The first is that human behaviour is caused. Secondly, human behaviour is goal directed.

The conscious actions normally taken by people are caused by two things:

(1) environment factors,

(2) factors in our heredity that affect our behaviour.

Human behaviour is not only caused. It is also goal directed, i.e., it is pointed toward something.

In short, people’s behaviour:

(1) May be caused by the way they perceive the world,

(2) Is directed toward achieving a certain goal, and

(3) Results in motivation to achieve that goal.

These points are illustrated in Fig.13.6.

Thus it is clear from Fig.13.6 that the motivational process is basically one of causation. Needs (motives) cause an inner desire to overcome some deficiencies or imbalance a person is experiencing. Stimuli (in the form of incentives) are then applied to cause a person to respond and behave in such a way that the goal of need satisfaction is achieved and the organisation accomplishes its desired performance. Some degree of predictability is observed throughout the chain of events and the actions are not totally unsystematic or random in nature.

Application of Knowledge:

The entire discussion of human motivation is based on the assumption that if a manager understands human behaviour he can better predict human behaviour and he can better control it. Consequently, understanding this process contributes to success in ensuing that people in organisations collaborate in their joint endeavour to raise productivity.

Project Report # 8. Theories of Motivation:

i. Work Redesign Theory of Motivation:

The work redesign theory developed by Richard Hackman and his associates evolved out of Herzberg’s theory. This theory is based on two important aspects of work — job enlargement and job enrichment. The former refers to increasing the number of operations an individual performs in a given job cycle.

For example; a worker on an automobile assembly line who performs five distinct operations during his job cycle holds a larger job than an employee who performs only four. On the contrary, the latter concerns the amount of responsibility an individual is able to exercise in his work environment. Herzberg’s hygiene factor and motivation factors are directly related to these two issues.

According to motivation-hygiene theory job enlargement is related to hygiene factors because the context of the work rather than its content is involved.Research on automobile workers lends support to this theory.

Their work is monotonous but the degree of monotony can be reduced by permitting the workers to perform five operations rather than only four or three. Thus, if a job is enlarged the tendency of workers to escape from the work environment by means of absenteeism or termination should decrease.

On the contrary, job enrichment involves the context of the work. Since it has to do with motivation factors, if affects a worker’s personal feeling about his job. A manager, for instance, can enrich the job of engineering draftsman by permitting him to perform work normally reserved for fully qualified engineers. Therefore, job enrichment implies that the individual assumes responsibilities not delegated to him previously.

This idea gets adequate empirical support. Some studies have discovered the link between job enrichment and productivity and high levels of absenteeism and turnover.

Job Diagnostic Survey:

The work redesign theory differs from motivation-hygiene theory in terms of at least one critical criterion: it is based on the assumption that individuals differ significantly in terms of the degree to which they will respond positively when jobs are enriched.

Hackman’s original approach was carried a step ahead by Hackman himself and Georgy Oldham in 1980. They developed a questionnaire — the ‘Job Diagnostic Survey’ — designed to measure the degree to which a job is enriched.

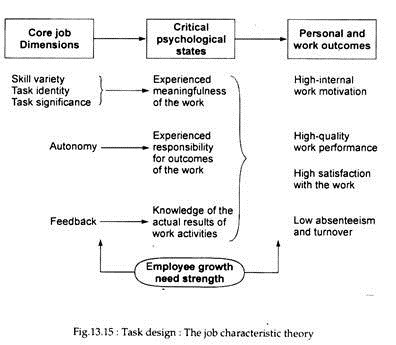

These two writers focus on five dimensions of a job:

1. Skill Variety:

The degree to which a job requires diverse skills.

2. Task Identity:

The degree to which a job demands completion of a whole and identifiable piece of work. To put it differently, the individual does the task from beginning to end with a visible outcome.

3. Task Significance:

The degree to which a job has substantial impact on the lives and works of other people, whether within the organisation, or in the external environment.

4. Autonomy:

The degree to which a job provides adequate freedom, independence, and discretion to the individual in scheduling the work and in determining the procedures used to carry it out.

5. Feedback:

The degree to which carrying out the activities included in a job results in the individual obtaining direct and clear information about the effectiveness of his performance. On the basis of these definitions Hackman and Oldham developed the following formula to study the degree to which a job is enriched:

On the basis of these definitions Hackman and Oldham developed the following formula to study the degree to which a job is enriched:

Explanation of the Theory. The redesign of motivation is illustrated in Fig.13.15.

The figure shows that the core job dimensions are inseparably linked up with critical psychological states. For instance, the theory relates a high degree of skill variety to a heightened sense of experienced meaningfulness of the work.

If emphasis is placed on all the core job dimensions there will be an increase in such personal and work outcomes as a high degree of internal work motivation and a high level of job satisfaction.

However, as M. J. Gannon has pointed out:

“The relationship between core job dimensions and outcomes is moderated by a key variable: the employee growth need strength or the degree torn which employee manifests a desire to satisfy higher-order needs”.

From this perspective it should be clear why job enlargement will be successful only if an individual possesses a high need, management may want to provide training designed to increase it before enriching job. This approach seems to be quite consistent with the contingency or situational theory of management.

ii. Expectancy Theory:

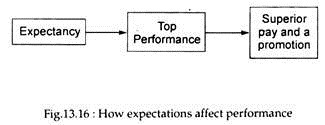

It may be noted at the outset that the expectancy theory emphasises perceptions of behaviour rather than actual behaviour. Basically, expectancy theory suggests that motivation depends on two things: haw much we want something and how likely we think we are able to get it.

According to this theory; an individual will be motivated to produce a level if he perceives that his effort will result in successful performance. This perceived link between effort and performance is called the effort-performance linkage.

The second assumption of the theory is that the individual must perceive that there will be a suitable reward for appropriate performance. The third assumption is that the individual desires these rewards. This assumption is most important, for an individual may receive adequate rewards such as pay incentives and higher levels of responsibility but he may not have a great desire for them.

Unlike the content theories (such as the hierarchy of needs theory or the two-factor theory), expectancy theory does not make any assumption about the nature of the need, such as lower-order versus higher-order needs. Instead, the individual must assign a weight to a particular job factor that ostensibly is satisfying a specific need.

The concept of expectancy is related to motivation as follows. Individuals are predicted to be high performers when they see the following:

(1) A high probability that their efforts will lead to high performance,

(2) A high probability that high performance will lead to favourable outcomes, and

(3) That these outcomes will, on balance, be positively attractive to them.

Basic Concepts:

The theory states that in most cases work behaviour can be explained by a basic fact: employees determine in advance what their behaviour may accomplish and the value they assign to alternative possible accomplishments or outcomes.

Fig 13.16 shows that if one expects hard work and performance to lead to higher pay and promotion, one will assign a high value on both — receiving higher pay initially and getting a promotion thereafter. In this situation, if the worker has the ability to do the work, he will probably be inclined to put forth a strong effort to receive the higher pay and earn promotion.

Some other variables may also be introduced in our scheme of things. Let us assume that one is starting one’s first job in a firm that pays at a piece-rate for each work done but pays additionally for each item produced over standard. If one adheres to the blue-collar work ethic, one’s expectancy regarding the work would probably approximate those shown in Fig.13.16.

One would probably consider the three output options of:

(1) Top performance,

(2) Average performance, and

(3) Low performance.

Then, on a subjective basis, one would assess the relative attractiveness of the three outcomes:

(1) Superior pay,

(2) Acceptance by the work group, and

(3) Not causing the standard to be enhanced.

The employer would like one to choose the first option.

While reinforcement theories focus on the objective relationship between performance and rewards, expectancy theories emphasise the perceived relationships—what does the person expect?

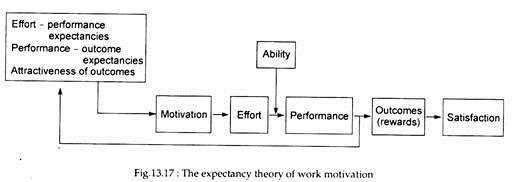

Expectancy concepts form the basis for a general model of behaviour in organisational settings, as shown in Fig. 13.17.

The operational side:

The theory can be made operational simply by means of an employee or managerial questionnaire.

Respondents are asked to indicate on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree), the degree to which they believe that they:

1. Can successfully perform the job;

2. Feel that specific rewards (e.g.., medical benefits, health care, paid holidays, pay, working conditions, increased responsibility, chances of promotion, etc.) are adequate; and (the individual is supposed to assign a value of 1 to 7 to each specific reward.)

3. Desire each specific reward, again using a 7-point scale for each specific reward.

Vroom Framework:

The formal expectancy framework which is used now was developed by Victor Vroom in 1964.

The expectancy theory is based on the following important assumptions:

1. Behaviour is determined by a combination of forces in the individual and forces in the environment.

2. People make decisions about their own behaviour in organisations.

3. Since people are different they have different types of needs, desires and goals.

4. People make choices from alternative plans of behaviour based on their perceptions of the extent to which a given behaviour will lead to desired outcomes.

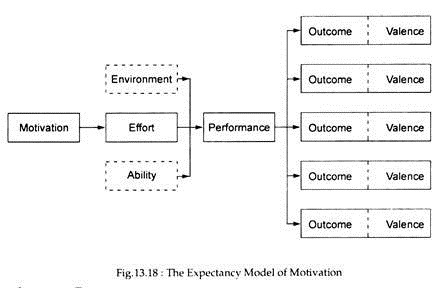

Fig. 13.18 summarises the basic expectancy model of employee motivation. The model suggests that motivation leads to effort and that effort, combined with employee ability and environmental factors, results in performance. Performance, in its turn, leads to various outcomes, each of which has an associated value. The value of an outcome to the individual is referred to as its valence.

However, the most important parts of the expectancy model cannot be shown in the figure. They are the individual’s expectation that effort will lead to high performance, that performance will lead to outcomes, and that each outcome will have the same kind of value.

Let us take the case of a young manager, who strongly wants a pay raise (an outcome). If he (she) perceives that a pay rise is likely to result from High performance, and if he (she) also believes that high, performance is likely to follow effort, then he (she) will be motivated to exert effort.

In this context, Vroom refers to the following two types of expectancy:

Effort-to-Performance Expectancy:

This is the individual’s perception of the probability that effort will lead to high performance.

Performance-to-Outcome Expectancy:

It is the individual’s perception that performance will lead to a specific outcome.

Outcomes and Valences:

Finally, expectancy theory recognises that an individual may experience a variety of outcomes or rewards in an organisational setting.

A high performer may get:

(1) Huge salary increment,

(2) Faster promotions, and

(3) More praise from the boss.

On the other hand, he (she) may also:

(4) Be subject to more stress and

(5) Incur resentment from co-workers and colleagues.

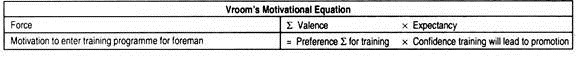

Vroom has outlined model of motivation that includes many of the earlier concepts.

The three dimensions to his model can be expressed by the following formula:

Force (of motivation) = Σ valence x expectancy

Vroom’s theory states that people will evaluate various behaviour strategies on the basis of the following two things:

(1) The effort required for performance,

(2) Whether the performance will have a desired outcome to the employee.

Three variables included in the theory are the following:

1. Valence:

How attractive is the reward? This is the strength or importance of the reward to the employee. It deals with his unsatisfied need.

2. Instrumentality (Force):

How strong is the chance (possibility) of a certain level of performance leading to the desired outcomes as a result of the performance. This is known as the force.

Vroom defines force as “an algebraic sum of the products of the valences of all outcomes and the strength of expectancies that the act will be followed by the attainment of these outcomes.”

In fact, the concept of force as it is explained by Vroom is s3aionymous with the word ‘motivation’ as it is used by most persons.

His formula can be illustrated below:

3. Expectancy:

Will the effort be enough to achieve performance? This entails an evaluation of how much effort the performance will take and the probability of achieving performance.

Vroom’s expectancy theory is one of choice of the process by which an individual seeks one outcome rather than another. However, an outcome includes both the behaviour (performance) and the reward associated with it. Thus this theory enables one to understand why an individual must have some alternatives which he can reject.

According to Vroom, people are motivated to work if they:

(1) Expect enhanced effort to lead to reward and

(2) Value the rewards resulting from their efforts.

Thus managers obtain the following result:

Motivation = expectancy that increased effort will lead to increased rewards x value to the individual of the rewards resulting from his or her efforts.

The theory predicts that if individuals perceive that superior performers will receive proper rewards they will be motivated to put forth the necessary effort. This conclusion is based on the assumption that the individuals have the abilities to do the work and their expectation is that the organisation will reward superior performance.

On this point, the expectancy theory differs from the content theories. Rather, the former goes beyond the latter.

As Griffin has rightly commented:

“Different people have different needs, and they will try to satisfy these needs in different ways. For an employee who has a high need for achievement and a low need for affiliation, the pay raise and promotions as outcomes of high performance might have positive valences. For a different employee with a low need for achievement and a high need for affiliation, the pay raise, promotions and praise might all have positive valences, whereas both resentment and stress could have negative valences”.

iii. Reinforcement or Operant Conditioning Theory:

Another theory developed by B.F. Skinner is known as operant conditioning or reinforcement theory. It is receiving growing attention as having potential to influence and change work behaviour modification. Also known as incentive theories or operant conditioning, reinforcement theories are based on a fundamental principle of learning—the Law of Effect.

Its statement is simple: behaviour that is rewarded tends to be repeated; behaviour that is not rewarded tends not to be repeated. If management rewards behaviors such as high quality work, high productivity, timely reports, and creative suggestions, these behaviors are likely to increase.

However, the converse is also true: managers should not expect sustained, high performance from employees if they consistently ignore employees’ performance and contributions. Performance is a combination of effort and ability, that is, an individual’s skills, training, information and talents.

Performance, in turn, leads to certain outcomes (rewards). Outcomes (positive or negative) may result either from the environment (e.g., supervisors, coworkers, or the organisation’s reward system) or from performance of a task itself (e.g., feelings of accomplishment, personal worth, or achievement).

Sometimes, people perform but do receive rewards. However, as performance rewards process occurs again and again, actual events provide further information to support a person’s beliefs (expectancies), and beliefs affect future motivation. This influence is shown in Fig. 13.22 by the arrow connecting the performance-outcome link with expectancies.

The model also suggests that satisfaction is best characterised as a result of performance rather than as a cause of it. However, satisfaction can increase people’s motivation by strengthening their beliefs about the consequences of performance. It can also decrease the importance of outcomes (as with Big Macs, a satisfied need is not a motivator) and, as a result, lower motivation for performances linked to whatever reward has become less important.

Don’t be deceived by the simplicity of the model or lulled into believing that all a manager must do to motivate employees is to relate pay and other valued rewards to obtainable levels of performance. Such a link is insufficient on its own, and it is also difficult to establish.

For employees to believe that a pay-for-performance relationship exists, an organisation must establish a visible connection between performance and rewards, and it must generate trust and credibility among its workforce. The belief that performance will lead to rewards is a prediction about what will happen in the future.

For individuals to make this kind of prediction, they have to trust the system that is promising them rewards. If this occurs, and if they see clear linkages between rewards and their behaviour, they will be motivated to perform well.

In this context, we may alter to the role MBO as a motivational technique. Recall that MBO is a process of collaborative goal setting between a manager and a subordinate with the understanding that the degree of goal attainment by the subordinate will be a major factor in evaluating and rewarding the subordinate’s performance.

The role of MBO as a motivational technique is perhaps best seen from the standpoint of a expectancy theory. By sitting down with a subordinate, jointly establishing goals for the subordinate, and agreeing that future rewards will be based on goal attainment, the manager is clarifying both the effort-to-performance expectancy and the performance-to-reward expectancy. Then, if the available rewards have a positive valence for the subordinate, be or she should be more motivated to work toward the goals that merit them.

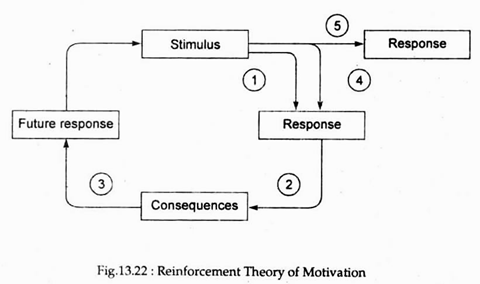

Recall that the final element of the motivational process outlined in Fig. 13.22 concerns reinforcement. We have noted that content perspectives relate to the needs of motives that stimulate behaviour and process perspectives explain how people choose various behaviours to achieve goals and how they evaluate the equity of the rewards they get for attaining those goals. Skinner’s reinforcement perspective on motivation explains the role of those rewards as they cause behaviour to change or remain the same over time.

To be more specific, reinforcement theory is based on the fairly simple assumption that behaviour that results in rewarding consequences is likely to be repeated, whereas behaviour that results in pushing consequences is less likely to be repeated.

How the Theory Operates:

Operant conditioning is the basis of behavioural management. It is based primarily on Edward Thorndike’s law of effect: behaviour followed by desirable or pleasant consequences will be repeated, while behaviour not followed by pleasant consequences will not be repeated. Thus behaviour is influenced or shaped in the way the environment (the organisation) desires.

A key concept underlying the theory is that of reinforces — any consequence of behaviour, assuming that the reinforces is available when the desired behaviour occurs. Management can have recourse to a variety of reinforces: money, extra time off, praise, fringe benefits, and so forth.

Skinner distinguishes between reinforcement, the presentation of an attractive reward following a response or the removal of an unpleasant or negative condition following a response, and punishment, the reverse of reinforcement.

The theory emphasises the point that the behaviour of an individual in a situation is influenced by the rewards or penalties that he (she) experienced in a similar situation.

Fig. 13.22 gives an alternative view of the motivation process in term of reinforcement theory. The starting point is a stimulus which can be interpreted as the needs or motives that trigger behaviour. The individual follows path 1 to a response.

As a result of this response, the individual faces a variety of consequences. This point is indicated by path 2. The value of those consequences affects future responses, as is indicated by path 3. If the consequences were pleasant or desirable, the individual will, in all likelihood, choose the same response (path 4) — the next time he/(she) encounters the same stimulus. But, if the original consequences were unpleasant or undesirable, a different response (path 5) is more likely.

For the sake of illustration let us consider the case of an employee trying to get a pay hike. If he starts working harder and subsequently succeeds in getting an income (or a pay raise), his behaviour has been reinforced.

The next time he wants a raise, he is likely to try working harder again. By contrast, if his additional effort failed to generate the desired outcome, i.e., a pay raise, he is likely to try other behaviours (such as buttering up the boss or even threatening to quit).

iv. Goal-Setting Theory of Motivation:

Goal-setting is one of the best accepted motivational strategies in organisational science. There are three related reasons why it affects performance. One, it has a directive effect — that is, it focuses activity in one particular direction. Two, given that a goal is accepted, people tend to exert effort in proportion to the difficulty of the goal.

Three, difficult goals lead to more persistence (i.e., directed effort over time) than easy goals do. These three dimensions — direction (choice), effort, and persistence — are central to the motivational process.

The goal-setting theory has been developed by Edwin Locke.

He argued that there are two cognitive determinants of behaviour:

(1) Values and

(2) Intentions (goals).

A value is something (such as an emotion or desire) the individual acts to gain or keep.

Intentions are goals that individuals seek to attain for satisfying their desires or emotions. Even when a gain is not attained, the individual experiences responses when he undertakes activity based on them. This, in directionality or process model may be presented as follows:

Empirical research has provided ample support for the proposition that the setting of specific, hard but attainable goals is related to much higher levels of performance than is the setting of diffuse, easy or moderate goal (such as ‘Do the best you can’.) Locke has shown, through his own research, that even individuals, trying for a goal so high they rarely reach it, perform better than those who are attempting to attain easy goals. Usually a group sets higher goals than a supervisor assigns.

Locke has added a qualifying clause: goals must be accepted. In general assigned work goals are more generally accepted than self-set goals. Individuals willingly work hard when they known exactly what is required of them. Another qualifier is that specific goals will improve performance only when accompanied by feedback or knowledge of results.

v. Attribution Theory:

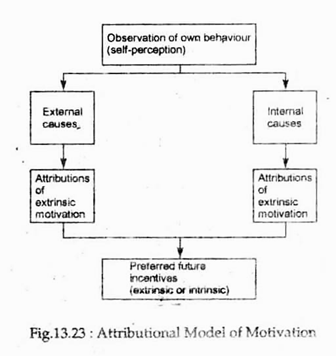

Michael Ross had suggested in 1985 that individuals observe behaviour and then attribute causes to that behaviour. This is the essence of attribution theory. The essence of the theory is illustrated in Fig.13.23, which indicates that each individual observes his (her) own behaviour (with potential major problems related to self-perception) and decides whether that behaviour is primarily motivated by internal or external factors. That decision, then, shapes the individual’s responses to future motivated factors.

Craig A. Anderson has pointed out that an individual who has decided that he(she) is intrinsically motivated, by the challenging nature of the task, for instance, will seek more internal motivational factors in the future.

In a like manner, an individual who has decided that he(she) is motivated more by extrinsic factors, such as pay, will seek more of those in the future. Individuals will not seek more of those factors that they feel ‘fit’ themselves, but they will also value more and so respond more quickly and strongly to them.

Project Report # 9. Role of Money in Motivation Theory:

It is often felt that money can be a powerful force in motivation if — and only if — it is directly related to achievement and performance. In reality many employees expect hard work and accomplishment to lead to promotions and increases in pay. Organisations that enforce such policies are likely to benefit from an environment where productivity, achievement and excellence are highly valued.

However, there are diverse motivational factors influencing employee behaviour. It is virtually impossible to identify and isolate any one variable as the specific stimulus to motivated behaviour.

It is interesting to note that the motivational role of money is based on the law of effect. The essence of the law is that “behaviour followed by satisfying consequences tends to be repeated, whereas behaviour followed by unsatisfying consequences tends not to be repeated.”

There is hardly any doubt that money is an important motivator. One study found that monetary incentives, when used to reinforce goals, increase worker productivity by an average of 30%. Money not only satisfies basic needs for food and shelter, but also provides social position and power.

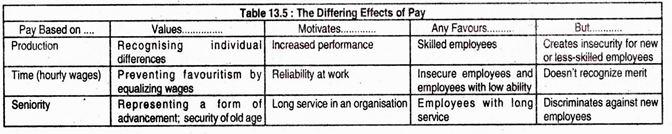

Additionally, it can provide recognition for high performance and lead to improved goal setting. There are different methods of making wage payment (or compensating the employees). Each has a different effect. These effects are shown on Table 13.5.

It is shown that:

(i) Pay tied to product (performance) usually provides improved performance for efficient employees but under the system inefficient employees (i.e., employees having less ability such as new entrants to the labour force) suffer from a sense of insecurity,

(ii) Time-based payment (i.e., pay on hourly basis) rewards job reliability,

(iii) Pay based on seniority is likely to encourage long-term service in an organisation but obviously discriminates against the new employee. Thus the effect of monetary incentive on motivation depends on what management wants and the specific situation of the person being rewarded.

Money is likely to be an effective motivator if it is able to meet long-term needs of employees. The high achiever who views money as a yardstick of his (her) achievement is likely to relish a differential pay system. C. R. Anderson has also pointed out that “the role of money is also related to a person’s cultural background. In an extreme example, people in under-developed countries may work for a few months and then quit, having accumulated enough money to return to their farms and villages and live for the rest of the year. Others, raised in a culture steeped in the traditions of wealth and material satisfaction, work continually when money is offered as an incentive.”

An organisation’s primary purpose in giving rewards is, of course, to influence employee behaviour. Extrinsic rewards are found to affect employee satisfaction, which, in turn, plays a major role in determining whether an employee will remain on the job or seek a new one. Reward systems also influence patterns of attendance and absenteeism. And, if rewards are based on actual performance, employees tend to work harder to earn those rewards.

Effect of Rewards on Motivation:

Reward systems are clearly related to the expectancy theory of motivation. The effort-to-performance expectancy is strongly influenced by the performance appraisal that is often a part of the reward system. That is, an employee is likely to put forth more effort if he or she knows that performance will be measured, evaluated and rewarded.

The performance-to-outcome expectancy is clearly affected by the extent to which the employee believes that performance will be followed by rewards. Finally, as expectancy theory predicts, each reward or potential reward has a somewhat different value for each employee. One person may want a promotion more than benefits; someone else may want just the opposite.

Characteristics of Effective Reward Systems:

What are the elements of an effective reward system? Lawler has also identified four major characteristics. First, the reward system must meet the needs of the individual for food, shelter and other necessities.

Next, the rewards should compare favourably with those offered by other organisations. Third, the distribution of rewards within the organisation must also be equitable. Finally, the reward system must recognise that different people have different needs and choose different paths to satisfy those needs.

Research Findings:

Empirical evidence suggests that money is most effective as a motivator on those jobs where individual efforts can lead to substantial increases in productivity, as in sales and various management jobs. USA’s Lincoln Electric Company has used an extensive bonus system for more than 30 years in which workers receive an average of 100% of their salary as annual payment (bonus). Among other goals, they are rewarded for production, quality, quantity, cost savings, creativity and co-operation.

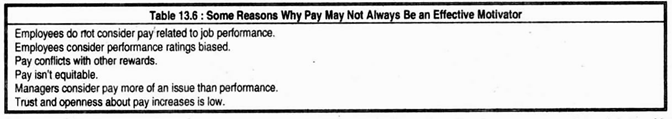

The experiences of a number of reputed U.S. and British companies indicate that there is hardly any doubt that money can be effective. Table 13.6 summarises the greatest pitfalls of administering money as a reward. More often than not money is not related to performance, or it is in conflict with other rewards.

Furthermore, it may not be administered fairly and equitability on most occasions since managers are more concerned with satisfactory pay increases than with improving performance. Other managers are likely to ignore intrinsic factors in favour of money, thus reducing job interest. Research and experience, however, have shown that when administered correctly, money can lead to tremendous productivity increases. Yet there are so many contrary findings.

One research project showed that when people believe that their efforts will lead to the desired reward, they will produce. It also showed that few individuals would engage in extended activities unless they believed that there was a direct link between what they did and the rewards they received.

However, it is becoming increasingly clear that “there is no direct relationship between the motivation to perform and job satisfaction. High motivation and performance can be associated with high satisfaction, but they can also be associated with low satisfaction — or may be entirely unrelated to satisfaction.” There are contradictory evidences.

Some managers see money as the primary motivator, ignoring the importance of the job itself. Many researchers conclude that “economic motive is no longer important, for employees have risen above the mundane demands of a physical existence and now have higher desires.”

In 1959 H. Behrend, a British sociologist, concluded that “it was impossible to find a direct statistical relationship between the application of incentive schemes and increased outputs. Physiological rewards may be more significant than material incentives in actual organisations and in experimental laboratories. Also, from an anthropological point of view, people in many cultures work for some reason other than material rewards.”

So the conclusion is that whether money acts as motivator largely depends on circumstances, in general “until employees are able to satisfy their physiological needs, compensation does not serve as a motivator. Wages and employment security may even motivate through the safety needs. Above that level, money tends to decline in importance as a stimulant to performance, and other stimulants acquire greater significance. At all levels, money serves as a symbol of success or achievement.”

To sum up:

(1) People having high achievement needs are likely to be high producers with or without financial incentives.

(2) Contrarily, those with low achievement needs must have the necessary monetary stimulus.

(3) Empirical research done in recent past indicates that women now tend to be much more concerned with money than men.

Rewards that Motivate Behaviour:

Managers have long observed that individual rewards – such as piece rate payments, sales commissions, and performance bonuses that tie individual rewards to individual performance — can be effective motivators if they “fit” the type of work performed. They are obviously inappropriate for assembly line jobs, where work is paced automatically, or for team jobs, where outcomes do not depend on the efforts of any single individual.

Nevertheless, research indicates that when incentives geared to reward individuals do fit the situation, performance increases an average of 30 percent, while incentives geared to reward groups increase performance an average of 18 percent.

However, the total compensation package each employee receives includes indirect as well as direct financial payments — benefits — cafetaria privileges, and company-subsidised tuition are examples of indirect payments, or “system rewards”, that employees receive simply for being members of the system.

They have little impact on the day- to-day performance of employees, but they do tie people to the system. They tend to reduce turnover and to increase loyalty to the company. As you can see, there are a number of alternative strategies available for building employee trust and productivity. However, at this point, you are probably also asking yourself “How do I proceed, and when should I use each strategy?”

Project Report # 10. How Occupational Level Affects Motivation?

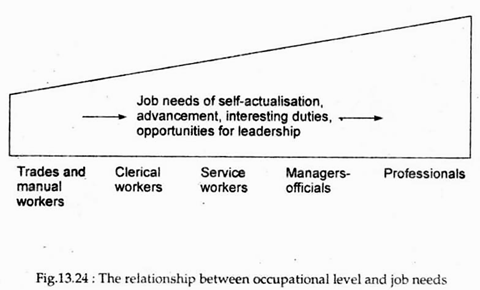

Motivation is different for different people. Yet it is possible to make some generalization about motivation at various occupational levels. Fig. 13.24 illustrates the relationship between occupational level and job needs.

A Study comparing needs of employees at the professional, managerial, official, service, clerical, and trades-manual levels reported that self-actualisation, advancement, interesting duties, and leadership were selected with increasing frequency from the trade group to the professionals.

On the contrary, the needs for respect, money, security, congeniality, and job security were selected more frequently by people who belonged to the lower socio-economic groups (such as trades and services) and least often by the managerial-official and professional groups. From this study emerges the conclusion that needs and occupational levels have a fairly consistent relationship.

Another study reported general agreement among scientists and managers concerning the incentive value of promotions, merit pay increases and more complex and challenging job assignments. There was a common feeling among these professionals that the most effective of non-financial incentive is recognition of performance. This study indicates that self-fulfillment is the prevalent need among scientists.

Self-employed professionals like doctors, lawyers and chartered accountants hardly face any problem with motivation. They are usually ‘self-motivated’. However, when they join companies as medical officers, legal advisers or accountants, problems arise.

Then the common motivational elements for most people having ambitions and initiative assume importance. Professional employees face another motivational problem: their dual allegiance is essential for management to learn how to motivate such professional people to fulfill organisational needs while at the same time satisfying the requirements of their own professional society.

In general, executives are motivated largely and primarily by money not because it satisfies their basic physiological needs but because it is a recognition of their status and position. Once this need for status is fulfilled executives usually seek the rewards of egoistic satisfaction and self-fulfillment. Therefore, they continue to stay in an organisation but cannot afford higher salaries just to satisfy these higher needs.

Job Satisfaction:

Studies made so far indicate very little, if any, direct relationship between job satisfaction and individual performance. In fact, in certain situations they are inversely related to each other. According to the expectancy theory job satisfaction is art outcome of the total motivational process.

From this perspective motivation may be viewed as the activation and direction of energy or behaviour while job satisfaction is to be treated as the cessation or gratification of behaviour. As Gannon putit: “when organisational members are so gratified, there tend to be lower rates of such outcomes as absenteeism, tardiness, and even turnover.”

If everyone is so satisfied that hardly any quitting occurs it becomes difficult for the organisation to hire additional employees and managers who can infuse the organisation with new ideas and perspectives. In fact, the equity theory is very much helpful in understanding job satisfaction.

The Work Ethic:

There are disagreements among writers on organisation and practising managers over the issue of whether employees and managers are less committed to work than employees and managers of earlier generations. However, job satisfaction and the ethic are different but not committed to work hard, or vice versa.

In fact, most people in the U.S.A. and Japan are very committed to the work ethic and empirical evidence suggests that the work ethic has not diminished over time. This is evident from the fact that most part-time workers seek full-time jobs and millions of women are now willing and eager to join the labour force.

Health and Non-Work Satisfaction:

Job satisfaction not only exerts influence on such outcomes as absenteeism and turnover, it is also related to physical and mental health. There is a strong correlation between job distribution and depression, physiological strain, and other indicators of poor health.

Thus, someone who is highly dissatisfied with his job should attempt to change his situation by such actions as having it redefined, becoming less committed to it and more committed to outside activities as a source of gratification, or even quitting.

Project Report # 11. Managing Motivation:

So long we have developed a number of theories of motivation. These theories explain why employees display different types of motivated behaviour. Now the relevant question is : what can an individual manager do to develop motivated workers?

Two important measures can be adopted by managers to motivate people: redesign of the job and creation of a supportive climate:

(a) Job Redesign:

Changing the nature of the task related activities of work is being used more and more as a motivational technique. Expectancy theory helps explain the role of job design in motivation. The basic idea is that they believe that doing so will lead to intrinsic rewards. Reward has shown that improvements in the design of work do often result in higher levels of employee motivation. One study has found that job redesign resulted in decreased turnover and improved employee motivation.

Job redesign requires a knowledge of and concern for the human qualities people bring with them to the organisation such as the needs and expectations of individuals, their perceptions and values, and their level of skills and abilities.

It also demands knowledge of job qualities (e.g., the physical and mental demands) made on individuals and the environment in which the job is performed. Job redesign usually tailors a job to fit the person who has to perform it.

The new entrant in the company’s work force is assigned pieces of the job in measured amounts until all the tasks have been learned and performed to standards. More experienced employees who are getting bored with their job may be assigned more challenging tasks and more flexibility or autonomy in dealing with them.

In redesigning jobs managers approach two directions: job scope and job depth. The former refers to the variety of tasks incorporated into the job, whereas the latter refers to the degree of discretion the person enjoys to alter the job. The attempts at job redesign include job enlargement, job rotation and job enrichment. We shall make a brief review of the concepts here.

(b) Job Enlargement:

Also known as job loading, job enlargement increases the variety or the number of tasks included in a job. It is an attempt to require ‘more of the same’ from an employee or to add other tasks containing an equal or lesser amount of burden or challenge. Job enlargement is liked by some people and not by others.

It is likely to add to a person’s individual job satisfaction and commitment to the job in those situations where people are suffering from an under-load and the boredom that is usually associated with it.

There is need to keep some people constantly busy and occupied with routine that they understand and have mastered. Their ‘sense of competence’ improves as their volume of output increases. Some people like more variety in their work, not more challenge.

(c) Job Rotation:

By adding variety and exposing people to the dependence of one job on others, job rotation assigns people to different jobs (tasks) on a purely temporary basis.

Job rotation is likely to help stimulate people to higher levels of contributions and renew people’s interests and enthusiasm. But it is unlikely to bear fruit if workers are asked to do more demanding, less desirable, or more time-consuming work for the same amount of pay.

The manager should take note of the reality that individual perceptions of persons. Moreover, additional time and money are required to keep rotation programmes going. Therefore, production, along with morale, may suffer.

(d) Job Enrichment:

Job enrichment applies Herzberg’s motivation factors to a job, thus permitting interested employees to satisfy some of their psychological needs. This is also known as vertical job loading.

In developing job enlargement, managers have the following specific areas to focus attention on:

1. Variety of tasks:

Introducing new and more difficult tasks not handled in the past.

2. Task importance:

Giving a person a complete natural Unit of work as also assigning individuals specific or specialized tasks that enable them to become experts.

3. Task responsibility:

Increasing the accountability of individuals to their own work and granting the employees additional authority in their activities.

4. Feedback:

Making periodic or specialised reports directly available to the worker himself (herself) rather than to a supervisor.

Since most efforts at job enrichment allow people more control over their work it is a useful tool to improve morale and performance. However, job enlargement, to bear fruit, must take place in an atmosphere of mutual trust between labour and management. Participation has to be voluntary and management must be competent in its day-to-day operations as well as its efforts at job enrichment so as to motivate employees.

Creating a Supportive Climate:

For motivating employees a manager has to provide a climate in which employees’ needs can be made clear. The primary components of such supportive climate are: adequate resources for goal accomplishment, support for reward systems, training and a well-conceived organisational format. The secondary components are: the manager’s personal philosophy, actions and expectation.

To build a supportive climate the manager has to assist the employee in the attainment of his goals — by removing barriers, developing mutual stability. Two other actions can improve the organisational climate: (a) openly appreciating the contributions of the employee’s need for equity. The employee must be made to feel that he is receiving a fair deal (exchange) for his output into the company and in comparison to other employees.

It is essential to develop and communicate to employees management expectations for performance and behaviour. Employees must know what the manager really wants so that they can function properly. With an optimum mix of these ingredients it is possible to develop a supportive climate. Such a climate, if established, will encourage motivated behaviour.

Motivation as more than Mere Techniques:

How important is need for motivation becomes quite clear from the fact that it is possible to buy a man’s time or physical presence at the work place. But it is not possible to buy enthusiasm, initiative, loyalty and devotion of hearts, minds and souls. These things are to be earned.

Thus there is the need to consider motivation as more inclusive than the mere application of some specific tool or device to stimulate increased output. It is a work-philosophy or a way of organisational life, founded on the needs and desires of employees.

This philosophy has to permeate the whole organisation, starting from the top, and attempt to create an environment in which all employees can voluntarily apply their capacities, as individuals, for raising total productivity. If this philosophy is adhered to, the details of motivation lose their significance.

It may be noted in this context that motivation theories have to be applied wisely so as to avoid undesirable or negative consequences. Such consequences are inevitable if certain theories which are not mature enough are applied widely.

In general, it is observed that the employees who receive rewards on the basis of their actual performance tend to do better than employees in groups where rewards are not based on performance. Moreover, if one understands the causes of human motivation one can predict that behaviour. And, to the extent it is possible to predict the behaviour, it can be brought under control.

Therefore, if managers are able to understand the relationship among incentives, motivation and productivity, they should be in a position to predict the Behaviour of subordinates. Consequently, managers who know this, and know how to apply given incentives, can hope to realise enhanced productivity from employees.

Project Report # 12. Integration and Application of Motivation Theories:

The object is to suggest meaningful prescription for managers to follow in motivating subordinates, based on the above brief review of motivation theories and types of rewards.

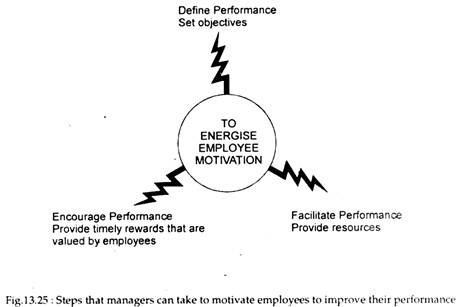

Broadly speaking, managers need to focus on three key areas of responsibility in order to coordinate and integrate human resource policy:

1. Performance definition.

2. Performance facilitation.

3. Performance encouragement.

These key areas are shown graphically in Fig. 13.25.

i. Performance Definition:

This is a description of what is expected of employees, plus the continuous orientation of employees toward effective job performance. Goal setting, as noted earlier, is an effective performance improvement strategy. It enhances accountability and clarifies the direction of employee effort.

The mere presence of goals, however, is not sufficient. Management must also be able to operationalise and, therefore, measure the accomplishment of goals. This is where performance standards play a vital role, for they specify what is “fully successful” performance.

The third aspect of performance definition is assessment. Regular assessment of progress toward goals encourages a continuing orientation toward job performance. If management takes the time to identify measurable goals but then fails to do assessment, it is asking for trouble.

This is so because, if there is no assessment of performance on these goals, the goals cannot motivate employees to improve their performance. The goals only send negative messages to employees regarding management’s commitment to the goals.

ii. Performance Facilitation:

This area of responsibility involves the elimination, of roadblocks to performance. Like performance definition, it has three aspects: removing performance obstacles, providing the means and adequate resources for performance and carefully selecting employees.

iii. Removal of Obstacles:

Improperly maintained equipment, delays in receiving supplies, poor physical design of work spaces, and inefficient work methods are obstacles to performance that management must eliminate in order to create highly supportive task environments. Otherwise, motivation will declineas employees become convinced that management does not really care about getting the job done.

iv. Adequate Resources:

A similar problem can arise when management fails to provide adequate financial, material, or human resources to get a job done right. Such a strategy is self-defeating and excessively costly in the long run, for employees begin to doubt whether their assigned tasks-can be done well.

v. Careful Selection of Employees:

This is essential to employee motivation to perform. Poor staffing procedures (“placing round pegs into square holes”) guarantee reduced motivation by placing employees in jobs that either demand too little of them or require more of them than they are qualified to do. Such a strategy results in over-staffing, excessive labor costs, and reduced productivity.

vi. Performance Encouragement:

This is the last key area of management responsibility in a coordinated approach to motivating employee performance.

It has five aspects:

1. Value of rewards.

2. Amount of rewards.

3. Timing of rewards.

4. Likelihood of rewards.

5. Equity, or fairness, of rewards.

The value and amount of the rewards relate to the choice of rewards to be used. Management – must offer rewards to employees {e.g., job redesign, flexible benefits systems, alternative work schedules) that employees personally value. Then a sufficient amount of reward must be offered to motivate the employee to put forth the effort required to receive it.

The timings and likelihood of rewards relate to the link between performance and outcomes. Whether the rewards are in the form of raises, incentive pay, promotions, or recognition for a job well done, timing and likelihood are fundamental to an effective reward system. If there is an excessive delay between effective performance and the receipt of rewards, the rewards lose their potential to motivate subsequent high performance.

Equity, or fairness, can also encourage or discourage effective performance. Fairness is related to, but not the same thing as, pay satisfaction. Satisfaction depends on the amount of reward received and on how much is still desired. Satisfaction is comprised of four aspects: the level of pay and benefits, the extent to which workers perceive their earnings as fair or deserved, comparisons with other people’s pay and non economic satisfactions — such as intrinsic satisfaction with the content of one’s work. Pay satisfaction certainly includes perceptions of fairness or unfairness and are distinctly different:

Equity, or fairness, depends on a comparison between the rewards one receives and one’s contributions to the organisation, relative to some comparison standard.

Such a standard might be:

Others — a comparison with other people, either within or outside the organisation.

Self-a comparison with one’s own rewards and contributions at a different time and/or with one’s own evolving views of self-worth.

Systems — a comparison with what the organisation has promised.

These comparison standards are used in varying degrees, depending on the availability of informatics and the relevance of the standard to the individual. Fairness is also related to employees’ understanding of their company’s pay system. Those who say they understand the system also tend to perceive it as fair.

The practices most likely to produce feelings of unfairness are adjustments in pay. However, organisations with carefully designed policies need ensure only that actions match intentions. It probably makes much less difference to employees’ perceptions of pay fairness what these policies are than seeing that they are followed consistently. But organisations that say one thing and do another find that pay injustice is one of their most important products.

Thus, while pay satisfaction is important, from the organisation’s standpoint it is of strategic importance that every employee consider his (her) pay to be fair, with some room for improvement. The point is that employees should be encouraged to improve their salaries, presumably by improving their performance.