Introduction to Operations Design:

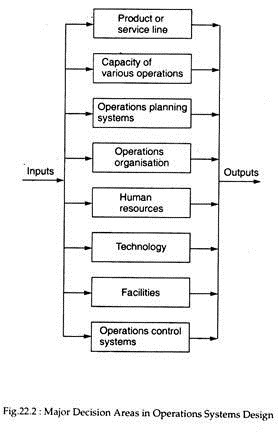

At its most basic level, planning for operations involves the design or re-design of the operations subsystem. Overall design goals are guided by higher organisational goals and the operations manager will then face various distinct operations decision areas in which design choices have been made.

As Fig. 22.2 shows, these decision areas are interrelated. Choices in any one area, such as designing an operations control system, must be consistent with choices in all the other areas, such as the types of interpersonal skills adopted in the operations system.

Furthermore, each choice involves tradeoffs; each alternative has both good and undesirable features that the manager must weigh.

Obviously, operations design is a complicated set of decisions involving many considerations which are briefly discussed below:

Product Line:

It is usually a combination of corporate, business and marketing functional strategies in an organisation that defines general product specifications, but the operations function then develops the detailed product specifications.

Proposed new products or changes in existing products may have high market potential, but their production may not be feasible within the existing operations system. Therefore, the operations manager is normally involved in the product line decisions of a typical organisation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

He might supply information relevant to the technological feasibility of new product proposals, identify the capital costs involved in modifying the operations system to build the new product, suggest alternative product designs that are more cost effective or that make production feasible in the existing system, or provide production cost information for setting the selling price of the new product.

Capacity:

The operations capacity decision involves choosing the amount of conversion capacity appropriate for the organisation. Although the operating capacity for firms that produce physical goods is usually expressed in terms of output, service organisations often express capacity in terms of input resources.

The capacity decision is truly a high-risk one, because of the uncertainties of future product demand and the large monetary stakes involved. If we want sufficient capacity to meet market demand, we must make some estimates of future demand.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We can build capacity that exceeds our needs and requires resource commitments (capital investment) that may never be recovered. Or, we can build a facility with a smaller capacity than expected demand; doing so may result in lost market opportunities, but it may also free capital resources for use elsewhere in the organisation. These kinds of trade-offs are inherent in the capacity decision.

Technology:

The operations technology used in producing physical goods can vary along a continuum from highly labour-intensive to highly capital-intensive. A home cleaning service and a football team are highly labour-intensive. It is people who do the work.

An automated plant, however, is highly capital-intensive. Expensive machinery does the work. The degree of mechanisation and automation chosen by an organisation has significant impact on output quality, production costs, labour and management skills required and the flexibility of its operations.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Although the technologies of most service organisations continue to be highly labour-intensive, relatively more capital-intensive options have evolved. Especially with increasing applications of computers, such traditionally labour-intensive professional services as medicine, law and education have adopted more capital-intensive technologies for creating and delivering their products.

Facilities:

How many production facilities are appropriate and where should they be located? It all depends. However, highly dissimilar production processes would create unnecessary congestion and confusion if grouped together.

The location of facilities must also be determined. Operations managers face the dilemma of whether to locate facilities near sources of supply (input resources) or near product markets (ease of output dispersal). This decision affects the capital cost of construction, the future costs of operations and the reliability of service to customers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

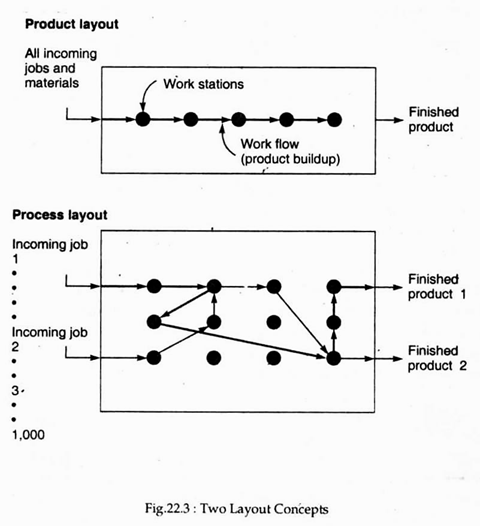

The choice of physical configuration, or the layout, of facilities is closely related to previous decisions on product or service line, capacity and operations technology. Some of the importance of the layout decision should not be over-emphasised. The two entirely different layout alternatives are shown in Fig. 22.3.

A product layout is appropriate when large quantities of a single product are needed. It makes sense to custom design a straight-line flow of work for this one product, in which a specific task is ‘performed at each work station as each unit flows through. Most large-scale assembly lines use this format.

Process layouts are used in operations settings that create a variety of products. The process layout uses the functional form of departmentalisation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Human resources:

Decisions about the types and amounts of human skills — labour, managerial, professional or technical — must be consistent with the technology and other decision areas. Similarly, methods chosen for selecting, training and rewarding employees must be compatible with choices made in the other areas.

These human resource decisions are closely related to location decisions, because the availability of different skills varies widely in different geographic regions.

Operations Planning, Organising and Control:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We have already considered the interrelationship of long-range strategic planning and the design of the operations function. In addition, operations managers must choose an operational planning process to achieve smooth day-to-day utilisation of resources. A good operations planning process in one environment may be ineffective or even highly disruptive in another.

A Composite Design Example:

The decisions made in each of the eight areas shown in Fig. 22.2 mesh to create a unique operations environment for each organisation. Any attempt to transpose one design into the other situation would result in an organisational mismatch and overall inefficiency.