Read this essay to learn about Decision-Making in an Organisation. After reading this essay you will learn about:- 1. Meaning of Decision-Making 2. Features of Decision-Making 3. Process 4. Approaches 5. Environment 6. Techniques 7. Models.

Contents:

- Essay on the Meaning of Decision-Making

- Essay on the Features of Decision-Making

- Essay on the Process of Decision-Making

- Essay on the Approaches to Decision-Making

- Essay on the Environment of Decision-Making

- Essay on the Techniques of Decision-Making

- Essay on the Models of Decision-Making

Essay # 1. Meaning of Decision-Making:

Decision-making means selecting a course of action out of alternative courses to solve a problem. Unless there is a problem, there is no decision-making. Decision-making and problem- solving are inter-related. It is the process through which managers identify organisational problems and solve them.

Decisions may be major or minor, strategic or operational, long-term or short-term. They are made for each functional area at each level. The importance of decisions, however, varies at each level. Long-term, major and strategic decisions are taken at the top level and relatively short-term, minor and operational decisions are taken at lower levels.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Decision-making precedes every managerial function. Decisions regarding what goals and ways to achieve them (decisions before planning), design of the organisation structure and span of management (decisions before organising), number and type of employees required, sources of recruitment, method of selection, training and development methods, best match between job description and job specification (decisions before staffing), incentive system, leadership styles and communication channel (decisions before directing) and techniques of control (decisions before controlling) are taken for smooth running and growth of business operations. Decision making is not easy.

All decisions are not based on past behaviour and practices (objective decision-making). Most of the decisions in the complex environment are subjective in nature. They are based on managers’ knowledge, value judgment, creativity and innovative abilities.

Managers do not make same decisions in same situations. It is situational in nature and depends upon managers’ psychology and perception of the situation. Decision-making is a modest attempt to match environmental opportunities with organisational strengths. It is based on forecasts and assumptions about environmental factors.

“A decision is a conscious choice to behave or to think in a particular way in a given set of circumstances. When a choice has been made, a decision has been made.” — J. W. Duncan

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Decision-making is “the selection of a course of action from among alternatives; it is the core of planning”. — Koontz and Weihrich

Decision-making is “the process through which managers identify organisational problems and attempt to resolve them”. — Bartol and Martin

Essay # 2. Features of Decision-Making:

Decision-making has the following features:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Decision-making is goal-oriented. The purpose of decision is to achieve a goal; sectional, departmental and organisational.

2. It is required for every managerial function though it is closely related to planning. How good are the decisions determines how effective are the organisational plans.

3. It is a process of choice; choosing a course of action out of various courses to solve a specific problem.

4. Problem-solving is the basis for decision-making as decisions are made to solve problems. Unless there are problems, there will be no decision-making.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

5. Decisions are made to solve organisational problems and exploit environmental opportunities. Both problems and opportunities, thus, need decision-making.

6. It is a pervasive process. Decisions are made in business and non-business organisations. In business organisations, they are made at all levels.

7. Decisions are made at all levels in the organisation; though nature and importance of decisions vary at different levels. However, organisational effectiveness is determined by the quality of decisions at all the levels.

8. It is required for every situation — certainty, risk or uncertainty.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

9. It is situational in nature. Different situations (both internal and external to the organisation) require different decisions. Not to make a decision is also a decision in some situations.

10. It is a continuous process. Managers continuously evaluate organisational activities and find problems that require decision-making.

11. It is an intellectual process. Managers use judgment, knowledge and creativity to develop solutions to the problem.

12. A manager is oriented towards making decisions rather than performing the actions personally; actions are carried out by others.

Essay # 3. Process of Decision-Making:

Decision-making process involves the following steps:

(i) Identify the Problem:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Decisions help to solve problems. As a first step to decision-making, therefore, managers identify the problem. Problem is any deviation from a set of expectations. It is the gap between the present and the desired state. Managers scan the internal and external environment to see if organisational operations conform to environmental standards. If not, there is a problem.

If sales target is 10,000 units per annum but actual sales are 7,000 units, managers sense problem in the company. The problem is identified with the marketing department. Managers use their judgment, imagination and experience to identify the problem as wrong identification leads to wrong decisions.

It is not necessary that managers take decisions only when the problems arise. They should also find the problems by searching for areas where threats or opportunities can arise and decide how to prevent threats and exploit the opportunities when they occur.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Guth and Taiguri assert that probable areas where managers would look for decision-making are guided by their value judgments like:

(a) Economic values:

Managers search for problems in areas where profit can be maximised.

(b) Theoretical values:

More than profits, managers are guided by forces to achieve long-term goals of the organisation (wealth maximisation) within the framework of environmental forces.

(c) Political values:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Managers backed by political values aim to achieve their personal goals.

Alarming Situations for Decision-making:

According to William Pounds, situations that call for decision-making fall into four categories:

(a) Deviation from past:

If current year’s performance significantly differs from past year’s performance, it requires decision-making. For example, sales of the current year fall significantly short of last year’s sales. It signals a problem that requires decision-making.

(b) Deviation from plans:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If actual performance is not in accordance with the planned performance, it requires decision-making. If actual sales are less than planned sales, managers should decide about how to increase the sales.

(c) Deviation noticed by others:

If quality of goods or standards of working hours are not adhered to, the matter may come to the notice of managers through customers or supervisors and, thus, needs decision-making.

(d) Perception about competitors:

If managers perceive that competitors are following a new strategy for creating customer loyalty or upgrading their technology to reduce cost of production, it requires immediate decision-making by managers. Decision-making is required not only to meet inter-organisational competition but also at the intra-organisation level.

Where a company has different plants or units, managers compare the performance of one unit with that of another and if there is deviation in performance of any unit, they decide about improving the performance of the unit not doing well.

(ii) Diagnose the Problem:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Diagnosis involves identifying the problem through its symptoms. Symptoms which indicate deviation from the standard objectives or actions indicate a problem that needs to be solved through the decision-making process.

Diagnosis involves identifying gap between the present and the future, identifying reasons why this gap has arisen and then going to the depth of the problem through decision-making. Managers collect facts and information to find cause of the problem. Diagnosis helps to define the problem; its causes, dimensions, degree of severity, magnitude and origin so that remedial action can be taken.

Managers get to the core of the problem and isolate it in a separate category of operations called the problem-solving area. In the above example, managers search for reasons of low sales. It could be low quality, poor promotion, better product introduced by competitors etc. The exact reason is found so that problem is diagnosed.

(iii) Establish Objectives:

Objective is the end result that managers achieve through the decision making process. Establishing objectives means deciding to solve the problem. The resolution forms the objective of decision-making. If the reason for low sales is poor salesmanship, managers form the objective to improve the skills of salesmen to promote sales.

Henry Mintzberg, Duree Raisignhani and Andre Theoret explain three types of problems that require decision-making:

(a) Crisis:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is a situation which requires immediate attention of managers and decisions to solve the problems. For example, if workers go on strike, management cannot sit back to think and take action. The problem needs to be immediately resolved.

(b) Non-crisis:

These problems do not require immediate attention as they can be resolved over a period of time. Most of the decisions relate to situations/problems which are non-crisis in nature. An employee who is regularly late for work represents a non-crisis problem. “A non-crisis problem is an issue that requires resolution but does not simultaneously have the importance and immediacy characteristic of a crisis.”

(c) Opportunity:

The situations of crisis and non-crisis reflect difficulties or problems that need to be solved but opportunities offer ideas which improve organisational efficiency. Managers reflected in take action immediately when opportunities are offered by the environmental forces to gain edge over competitors. Opportunities offer new ideas and directions to organisation’s operations. They provide profits to the organisation if timely decisions are made by managers.

(iv) Collect Information:

In order to generate alternatives to solve the problem, managers collect information from the internal and external environment. Information provides inputs for generating solutions. Information can be quantitative or qualitative. It should be reliable, adequate and timely so that right action can be taken at the right time.

(v) Generate Alternatives:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Alternatives means developing two or more ways of solving the problem. Managers develop as many solutions as possible to choose the best, creative and most applicable alternative to solve the problem. Alternatives are required as generally, there is more than one way to solve the problem. The decision-maker should collect information with respect to feasible solutions that can provide satisfactory solution to the problem.

Though the decision-maker attempts to generate maximum information on which he bases his decisions, it may not always be possible either because of his physical, mental or time constraints or because of environmental constraints (the complete information may not be available).

He should, thus, generate alternatives on the basis of principle of limiting factor, that is, factors which limit the generation of alternatives should not be part of the decision alternatives. For example, if the decision-maker is constrained by time factor as the decision relates to the situation of crisis, he cannot wait for information that takes long time to collect to generate decision alternatives. He will not consider options where collecting information is time-consuming.

Alternatives can be generated in the following ways:

(a) The decision-maker uses his past experience to deal with problem situations that have occurred before. Though past actions form the basis for future actions, it may not be possible in case of situations where present challenges are significantly different from the past challenges.

(b) He adopts the decision taken by other managers in the same or different companies if the outcome of that decision, in a similar situation, was positive. Changes are, however, made in the light of present circumstances which require decision-making.

(c) He can adopt scientific and creative techniques to solve problems.

A.F. Osborn identifies four principles which help to generate alternatives:

(a) Do not criticize ideas while generating possible solutions:

Managers should react positively to all the ideas. Criticism at the stage of generating solutions can limit the number of alternatives.

(b) Freewheel:

Even the remote solutions which may not be relevant to the problem should be taken into consideration. These may not be acceptable independently but may be useful in the overall decision-making process.

(c) Offer as many ideas as possible:

Managers should invite maximum ideas for framing solutions to the problem. Large number of ideas helps to arrive at effective solution to the problem.

(d) Combine and improve on ideas that have been offered:

Combination of all the ideas helps to arrive at the best solution.

(vi) Evaluate Alternatives:

The alternatives are weighed against each other with respect to their strengths and weaknesses. They are useful if they help to achieve the objective. Alternatives are evaluated in terms of acceptable criteria to analyse their impact on the problem.

Alternatives are evaluated against the following quantitative and qualitative criteria:

(a) Costs:

Alternatives should not be costly. Improving the skills of salesmen by firing the existing salesmen and hiring new ones may involve strain on financial resources. Such alternatives should be avoided.

Resources:

The alternatives should fit into the organisation’s resource structure. They should be feasible with respect to budgets, policies and technological set up of the organisation.

Acceptable:

Alternatives should be acceptable to decision-makers and those who are affected by the decisions. If managers want to increase sales by spending more on advertisement but finance department refuses to accept the financial burden on advertisement, this alternative should be dropped.

Reversible:

A decision is reversible if it can be taken back and other measures can be adopted. In the above example, if decision to increase sales by increasing cost of advertisement is not acceptable to all in the organisation, it can be reversed but decision to invest in land and building cannot be easily reversed as huge amount of time, effort and money are involved in it. Reversibility of the decision is an important factor that helps to evaluate alternatives.

The evaluation of alternatives is, thus, based on the following criteria:

(a) Tangible factors like cost and resources are the quantitative factors that help in evaluation of alternatives, though, once the decision is implemented, actual cost and resource adjustment may be different from that predicted. This is because of the limitations or constraints under which managers make the decisions.

(b) Intangible factors like acceptability and reversibility are the qualitative factors that cannot be measured but have significant impact on evaluation of various decision alternatives. Both these factors help in evaluation of alternatives so that best and satisfactory alternative can be chosen that contributes to organisational objectives.

(vii) Select the Alternative:

After evaluating the alternatives against accepted criteria, managers screen the non-feasible alternatives and select the most appropriate alternative to achieve the desired objective. Though the chosen alternative may not be the best, it is the most satisfactory alternative in light of the decision criteria of tangible and intangible factors that will contribute to organisational objectives.

Alternative can be selected through the following approaches:

(a) Experience:

Past experience guides the future. Based on past experience, managers choose alternatives which they have chosen earlier to solve similar problems. Managers follow past actions, search for their successes and failures, analyse them in the context of future environment and select the most suitable alternative that suits the present situation.

(b) Experimentation:

An alternative to experience is experimentation where each alternative is put to practice and the most suitable alternative is selected. This method is costly as implementation of every alternative to the decision-making situation involves heavy time and capital expenditure.

Testing each alternative, therefore, is not feasible. This method is generally used in marketing where pre-launch helps in knowing acceptability of the product so that changes in product features can be made before launching the final product in the market.

(c) Research and analysis:

It helps to search and analyse the impact of future variables on the present situations, apply mathematical models and select the most suitable alternative. This method is more suitable and less costly, in terms of time and money, as compared to experimentation and experience.

(viii) Implement the Alternative:

Though decision-making process is complete once the decision alternative is selected, managers should ensure that the decision helps in achieving the desired objective. Therefore, it is important that implementation of the alternative and its monitoring (or feedback) form part of the decision-making process.

The selected alternative is accepted and implemented by the organisational members. Implementation must be planned. Those who will be affected by implementation should participate in the implementation process to make it effective and fruitful.

Implementation of the alternative ensures the following:

(a) The selected alternative is communicated to everyone in the organisation.

(b) Changes in the organisation structure because of implementation are communicated to everyone in the organisation.

(c) Authority and responsibility for implementation are specifically assigned.

(d) Resources are allocated to departments to carry out the decisions.

(e) Budgets, schedules, procedures and controls are established to ensure effective implementation.

(f) A committed workforce is promoted. Unless everyone is committed to the decision, the desired outcome will not be achieved.

(ix) Monitor the Implementation:

The implementation of decision is aimed to achieve the objective for which it is chosen. The outcome of decision indicates whether the right decision is chosen and implemented or not. The implementation process is monitored to know its acceptability amongst organisational members. The alternative is regularly monitored, through progress reports, to see whether the objective for which it was selected is achieved or not.

Through feedback received from the results or outcomes of decisions, managers take the follow-up action. If results deviate from the objectives, managers try to find out the reasons responsible for deviations and make corrections in the implementation process. It may even require review of the entire decision-making process.

A good decision, thus, requires that results of the decision should contribute to objectives of the decision and if required, changes should be made in the decisions in the light of changing circumstances. If results match the objectives, such alternative forms the basis for future decision-making.

Essay # 4. Approaches to Decision-Making:

Decisions can be taken in different ways.

Four main approaches to decision-making are discussed below:

(i) Centralised and Decentralised Approach:

In centralised approach to decision-making, maximum decisions are taken by top-level managers though some responsibility is delegated to middle-level managers. In the decentralised approach, decision-making authority is delegated to lower-level managers. In programmed decisions, decentralised approach is followed. Centralised approach is used to make non-programmed decisions.

(ii) Group and Individual Approach:

Managers take decisions with their employees/ subordinates in the group approach to decision-making. In the individual approach, decisions are taken by the manager alone. It is the one-manager decision-making approach.

The individual approach is appropriate when:

(1) There is urgency for taking decisions, i.e., decision maker has limited time to take a decision, and

(2) Resources are limited.

Cost of individual decision-making is less than group decision-making. Group decision-making, in most circumstances, is better than individual decision-making since decisions are based on extensive information. Group decisions are easier to implement as they involve moral commitment of the members to adhere to the decisions. This approach ensures better quality and greater accuracy of decisions. It also improves employees’ morale, job satisfaction, co-ordination and reduces labour turnover rate.

(iii) Participatory and Non-Participatory Approach:

In the participatory approach, managers seek opinion of those who are affected by the decisions. There is no formal gathering of superiors and subordinates, as in group decision-making. The decision-maker only seeks information and suggestions from subordinates and reserves the right of making decisions. There is increased participation of subordinates in achieving the decision objectives.

In the non-participatory approach, managers do not seek information from subordinates as the decisions do not directly affect them. They collect information, make decisions and communicate them to the organisational members.

(iv) Democratic and Consensus Approach:

In the democratic approach, decisions are based on voting by majority. In the consensus approach, participants discuss the matter and arrive at a general consensus. It is similar to group decision-making where many people are involved in the decision-making process.

However, in group decision-making, some people agree to others because of social or psychological pressures but in consensus decision-making, all members unanimously agree to the decision. Group decision-making reflects the opinion of a few and consensus decision-making reflects the opinion of all the group members.

Essay # 5. Environment of Decision-Making:

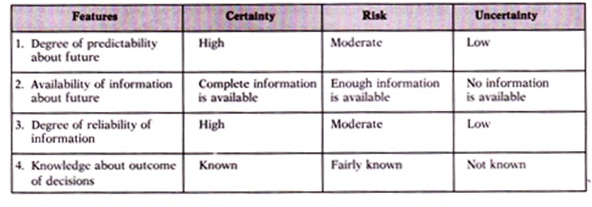

Environment of decision-making represents the known and unknown environmental variables in which decisions are made. Some decisions are taken in situations of complete certainty and others in the situation of complete/partial uncertainty.

Decision-making environment represents the situations in which decisions are made. Decision alternatives represent a course of action to be taken for future environmental conditions which vary along a continuum with perfect certainty at one end of the continuum and perfect certainty at the other.

Situations intermediate between the two extremes represent the conditions of risk, high or low, depending on their nearness towards uncertainty or certainty. The decision outcomes differ in different conditions.

The continuum representing the decision-making conditions can be represented as follows:

The environment represents three situations:

(i) Certainty:

In the environment of certainty, decision-makers have complete and reliable information about future. Information is reliable, correct and not too expensive. Results of each alternative can be predicted and therefore, managers can choose the best course of action.

For example, if managers want to launch a new product and they have to decide about whether to launch in Northern region or Southern region and they know that demand in Northern region would be Rs.80 lakh per annum and that in Southern region would be Rs. 60 lakh per annum, they would decide to launch the product in the Northern region as information they have fully supports this decision.

This is a situation of certainty where manager is sure about the demand. Such decisions will be perfect decisions and usually relate to conditions of immediate future. Managers are also sure of such decisions as they have proved to be successful in the past. There is absence of chance element as all factors that will affect the decision are assumed to be known and exact. These decisions are based on rational model of decision-making.

Such a situation does not exist in reality. In fact, managers make decisions on those aspects of environment about which information is available. They ignore the rest and call it a situation of certainty. All factors that affect the decisions are not always exact and also do not behave in the same way as they behaved in the past. Managers, therefore, have to assign probability to occurrence of such factors in future.

(ii) Risk:

This represents a situation where information about environment is incomplete. It is not even completely reliable. Alternative courses of action can be developed but outcome of decisions is not known. The expected results are not deterministic but only probabilistic.

Past usually provides the basis for future outcomes. In the decision to introduce a new product, managers can foresee the risk of competition in the market. However, the exact degree is not known. Most decisions are taken in the situation of risk.

These decisions are based on non-rational models of decision-making.

While most of the decisions are taken in the situation of risk, managers take into account two factors:

(a) The amount of risk in the decision.

(b) The ability and willingness of the organisations to accept decisions in that situation of risk.

Managers try to analyse the amount of risk in the decision through risk analysis where probabilities are assigned to the occurrence of events in future.

The probabilities can be assigned on the following basis:

(a) In some cases, the nature of decision allows the probability to be assigned on the basis of assumed conditions. For example, if managers want to assign probability to the decision situation as to whether the new product will succeed or not, they will assign the probability of 0.5 to each outcome. Though this method of prediction does not guarantee certainty of outcomes, it provides a fair guess work in situations when such decisions have been taken several times in the past.

(b) Probability can be assigned on the basis of empirical data. Depending upon the number of times that a solution has been able to solve a problem, managers can assign high probability to that decision (or solution) whenever that problem arises. For example, if advertisement on television has always proved successful in generating sales of a new product, managers will assign high probability to this mode of advertisement whenever they launch a new product.

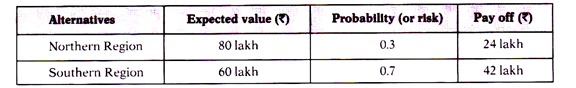

(c) Managers can use their judgment, knowledge and experience to assign probability to occurrence of various events in the event of absence of any information. When probability is multiplied with the expected value of decision alternatives, the payoff from that alternative can be determined. If managers feel that the probability of demand in the Northern region being Rs.80 lakh per annum is 0.3 and that it will be Rs.60 lakh per annum in Southern region is 0.7.

The pay off from the two alternatives shall be as follows:

The decision outcome can be different when risk factor is included in the decision alternatives. Thus, while it was more profitable to sell in North in situation of certainty, it becomes profitable to sell in South in situation of risk.

(iii) Uncertainty:

It is a situation where no information is available about future. Whatever information is available, it is not reliable. Decision alternatives are totally unpredictable. Outcomes of decisions cannot be predicted. Decisions are based on intuition and judgment. Some of the uncertain elements in the environment are economic, political, technological and natural changes which cannot be predicted and accounted for in the decision-making processes.

Since the manager does not have information upon which he can frame decisions or analyse them, he has to rely on one of the following decision criteria to make decisions:

(a) If the manager is optimistic in nature, he thinks positively about the factors that affect the decision. He selects the alternative which gives him maximum payoff out of the various alternatives that affect his decision. This criterion of maximising value of the decision is called maxi-max criterion as its objective is to earn maximum monetary payoff. It maximises the maximum payoff. In the above example, managers would launch the product in Northern region as it is expected to give a pay off of Rs. 80 lakh.

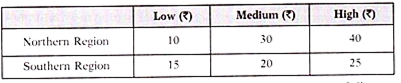

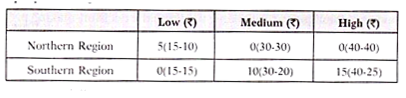

If demand in Northern and Southern regions is estimated for 3 different demand states; high, medium and low, the maxi-max criterion helps in deciding the most favourable monetary payoff for both the alternatives.

Managers will decide to sell in the Northern region in order to maximise monetary gain: Rs. 40 lakh. He chooses between 2 maximum gains: Rs. 40 lakh in Northern region and Rs. 25 lakh in Southern region. Possible losses and risk in achieving the target objectives are ignored.

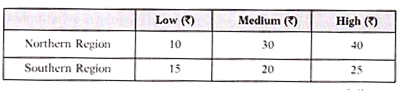

(b) If the manager is pessimistic in nature, instead of maximising the maximum returns, he aims to maximise the minimum return. The least favourable return is aimed to be maximised. If in the above example, the demand for product in the Northern region is assessed in 3 different states : low, medium and higher as Rs. 10 lakh, Rs. 30 lakh, Rs. 40 lakh respectively, and in the Southern region as 5 lakh, Rs.20 lakh and Rs.25 lakh, the decision maker is prepared for the worst to happen.

Thus, he chooses between Rs.10 lakh in Northern region and Rs. 15 lakh in Southern region. Out of the two minimum pay offs, he maximises the pay off in the Southern region and, thus, selects to launch the product in the Southern region. This criterion of maximising the minimum value of the decision alternatives is called maximin criterion as its objective is to select the maximum value out of the minimum values of various decision alternatives. It maximises the minimum pay off.

(c) Though the manager predicts the demand for different situations for different decision alternatives, there is always the risk that if he selects the most favourable payoff, that payoff may not actually occur so that managers regret the decision. Thus, the manager wants to minimise his regret as he does not know whether the selected alternative may or may not happen. He, therefore, chooses an alternative which minimizes his regret.

In the decision alternatives, as discussed in the following example:

If managers prepare a regret table for decision making it may be as follows:

Regret is compiled as follows:

Most favourable payoff for each event Less payoff for each alternative for each actual chosen event.

The table shows that if the firm chooses to sell in the Northern region, it faces a regret of Rs. 5 lakh in case demand is low. In case it chooses to sell in the Southern region, the regret is worth Rs. 10 lakh in medium event and Rs. 15 lakh if the demand is high.

Since managers aim to minimise the regret, the alternative of selling in the Northern region shall be chosen. This criterion of minimising the maximum regret (Rs. 10 lakh and Rs. 75 lakh) is called minimax criterion as its objective is to select the alternative which minimizes the risk.

(d) In the fourth decision criterion, the insufficient reason criterion, the decision-maker assigns equal probability to all the events (or demand states in this case) for different alternatives. As occurrence of any event is unknown, the decision maker believes that there are equal chances for all the events to occur.

The payoff expected from the two alternatives shall be as follows:

Northern Region = (Rs. 10 lakh + Rs. 30 lakh + Rs. 40 lakh)

= Rs. 80 lakh/3

= Rs. 26.67 lakh

Southern Region = (Rs. 15 lakh + Rs. 20 lakh + Rs. 25 lakh)

= Rs. 60 lakh/3

= Rs. 20 lakh

The decision alternative which gives maximum payoff shall be selected. Managers, thus, decide to launch the product in North. Depending on the number of decision alternatives and decision situations, decision makers apply these decision criteria in order to maximise organisational objective.

The following table explains the environmental situations that affect the decision-making processes:

Essay # 6. Techniques of Decision-Making:

Traditional Techniques of Decision-Making:

These techniques are divided into two groups:

1. Traditional techniques to make programmed decisions

2. Traditional techniques to make non-programmed decisions

1. Traditional Techniques to make Programmed Decisions:

Three generally accepted traditional techniques for making programmed decisions are:

(a) Habits:

Habits are the ways in which problems are solved according to pre-defined notions. Managers do not apply scientific techniques to solve problems. By solving the same problem in a defined way over and over again, managers form the habit of solving it in that manner. It does not require much of innovative thinking and initiative.

(b) Operating procedures:

Operating procedures are organisational habits. They guide decision-makers in solving problems in a pre-defined manner. They are more formal than habits. However, they are flexible and can be changed. Cases of absence without leave are not decided by managerial discretion. Standard procedures guide action against such cases.

(c) Organisation Structure:

It is a well-defined structure of authority-responsibility relationships. Every person knows his position in the organisation, authority to make decisions, extent to which it can be delegated to subordinates, the communication channel, persons to whom he has to report etc. which helps in solving programmed problems.

2. Traditional Techniques for making non-programmed decisions:

Managers solve unstructured, novel and non-repetitive problems through judgment, intuition and creativity. No scientific basis of decision-making is followed. These are more of personal qualities than techniques for problem-solving. They, therefore, vary from person to person. Every manager perceives the problem in his own way and solves it to the best of his judgment. No scientific techniques are used to solve the problems.

Modern Techniques of Decision-Making:

Modern techniques use mathematical models to solve business problems. They apply scientific and rational decision-making process to arrive at optimum solutions. They use quantifiable variables and establish relationships through mathematical equations and operations research techniques. They process large volume of data and establish relationships amongst them that affect the decision. They use computers for data processing and storage to solve complex management problems.

Use of quantitative tools results in a discipline called ‘Operations Research (OR)’. They help in making decisions under conditions of risk and uncertainty. Since OR techniques are quantitative in nature, they quantify variables in the problem in monetary terms in order to derive meaningful results.

These techniques can be used:

1. In wide areas of business like inventory valuation, materials handling, production, marketing, research and development, personnel etc.

2. To optimise the use of limited resources amongst various units in the organisation. Large-sized organisations have large number of inter-dependent units that compete for limited resources. OR techniques help to distribute the resources amongst various units in the best possible way that results in their optimum utilisation.

These techniques can be classified as follows:

1. Modern Techniques for Making Programmed Decisions:

These are as follows:

(a) Break-even technique:

It helps to determine the level of output at which total costs (variable costs and fixed costs) and total revenue are the same. Total profit at this volume, called the break-even point, is zero. It helps managers analyse economic feasibility of a proposal. For any level of output, the amount of profit can be known which serves as acceptance/rejection criterion of the proposal. It is only a rough estimate of assessing the project since it assumes a constant selling price and fixed cost which is not always so.

(b) Inventory models:

Firms carry buffer inventory to avoid running out of stock. Though this ensures regular supply of goods to customers, they incur costs to carry the inventory like handling costs, storage costs, insurance costs, opportunity cost of money tied in the inventory etc. These are known as carrying costs. In order to reduce these costs, firms keep minimum inventory in store and order fresh inventory when they need.

This reduces the carrying cost of inventory but the ordering cost goes up. These are the costs of placing an order and include cost of preparing the order and cost of receiving and inspecting the goods. Both the carrying and ordering costs operate in reverse direction.

Increase in one means decrease in the other. Sophisticated inventory models are available for management of inventory. They help in placing order for goods at the point where total of ordering costs and carrying costs is the least.

(c) Linear programming:

It is a technique of resource allocation that maximises output or minimizes costs through optimum allocation of resources (time, money, material, etc.). It is applied when resources are scarce and have to be optimally utilised so that output can be maximised out of limited resources. Linear programming is “a quantitative tool for planning how to allocate limited or scarce resources so that a single criterion or goal (often profits) is optimised.”

It aims to maximise profits or minimise costs by combining two variables which involve best use of resources. The (two) variables, dependent and independent must be linearly related, i.e., increase or decrease in the independent variable should result in a corresponding increase or decrease in the dependent variable.

Linear programming is, thus, a managerial tool that helps in optimum use of resources. Its use is facilitated through mathematical equations. ‘Linear’ defines proportional relationship amongst two or more variables, that is, increase in inputs should result in increase in outputs in the same proportion as increase in inputs. For example, if 10 units of input produce 20 units of output, 20 units of inputs should produce 40 units of output. If one worker produces 5 units, 2 workers should produce 10 units.

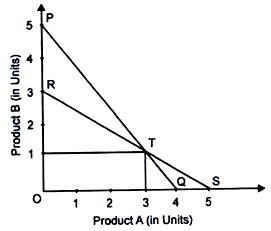

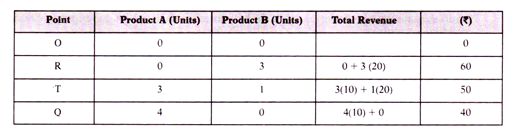

Use of linear programming in decision-making can be understood with the help of the following example:

1. A firm produces two products: A and B

2. Product A can be sold at 0 per unit and Product B can be sold at Rs. 20 per unit.

3. Both the products require use of 2 machines: I and II.

4. While machine I can be used for 20 hours, machine II can be used for 15 hours.

5. Product A requires 5 hours of Machine I, and Product B requires 4 hours of Machine I.

6. Product A requires 3 hours of Machine It, and Product B requires 5 hours of Machine II.

The firm wants to maximise its revenue by deciding the best combination of Product A and B that can be produced by optimising the use of 2 machines within the constraints that Machine I cannot work for more than 20 hours and Machine II cannot work for more than 15 hours.

This can be done as follows:

1. Production of Product A = X and Production of Product B = Y.

2. Total revenue of the firm from Product A and B: 10X + 20Y

3. Given the constraint if maximum time available on two machines (20 hours and 15 hours), and time required to produce each product.

The combination of two products to be produced within the constraints of time can be represented as follows:

5X + 4Y ≤ 20 (for machine I)

3X + 5 Y ≤ 15 (for machine II)

4. These constraints are plotted on a graph. Product A is shown on x-axis and product B is shown on y-axis.

As linear relationship is drawn amongst the variables, the equations for time constraints have to be represented by a straight line.

(i) The constraint 5X + 4Y ≤ 20 will be plotted by joining the two terminal points with a straight line. The terminal points assume that either (a) all the time on Machine I is used to produce product A, in which case, Y = 0 and X will be 4 units.

First point on x-axis will be, thus, 4 or (b) all the time on Machine I used to produce Product B, in which case, X = 0 and Y will be 5 units. Second point on Y-axis will be, thus, 5. These two points (4 on x-axis and 5 on y-axis are connected by a straight line PQ.

(ii) For machine II, the time constraint 3X + 5Y < 15 will have 5 units on x-axis and 3 units on y-axis.

(a) Assuming only Product A is produced on Machine II, 5 units of Product A will be produced.

(b) Assuming only Product B is produced on Machine II, 3 units of Product B will be produced.

The two points (5 on x-axis and 3 on y-axis) are connected by a straight line RS.

5. The region (ORTQ) formed by intersection of lines PQ and RS is the feasibility region which contains the optimum combination of two machines for two products, A and B. The possible combinations of Products A and B within the time constraints of Machines I and II will lie in the feasibility region of ORTQ. Various combinations of four corner points can be tested to find out the best combinations of Products A and B to be produced that will maximise revenue of the firm.

These are:

Within these constraints, revenue can be maximised at point R where Product A should not be produced and 3 units of Product B should be produced. This is a simple representation of how linear programming can help in optimising the use of resources (in this case, time). In actual business situations, firms have to choose amongst large number of products with large number of variables (time, money, labour hours etc.) with many constraints.

This will result in numerous equations that require the knowledge of advanced mathematics. Calculations, in such cases, become quite complicated and are, thus, facilitated through use of computers. Computers have eased finding out the optimum combinations of products through optimum use of resources.

(d) Simulation:

This technique is used to create artificial models of real life situations to study the impact of different variables on that situation. A model is prepared on the basis of empirical data and put to all kinds of influences, positive and negative which may affect the project, and final results are the predictions of actual results if the project in question is put to use.

For example, if a transportation company wants to make a road or rail system, it will prepare a simulation model to analyse the effect of all the factors (e.g., traffic signals, fly overs, other heavy and light traffic commuting on the road) and if this model appears to be feasible, actual construction of the rail/road system shall commence.

(e) Probability theory:

Probability is the number of times an outcome shall appear when an experiment is repeated. What is the probability that sales will increase if expenditure on advertisement is increased is answered through probability theory. These decisions are based on past experience and some amount of quantifiable data.

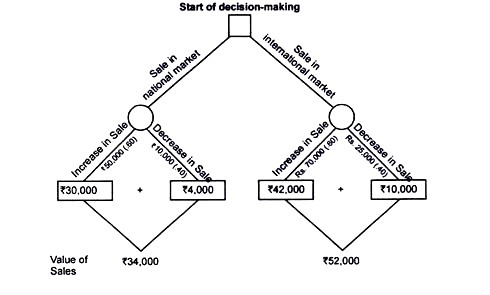

(f) Decision-tree:

It is a diagrammatic representation of future events that will occur when decisions are made under different options. It reflects outcomes and risks associated with each outcome. Each outcome or future event is evaluated in terms of desired results and the outcome which gives the maximum value is selected out of alternative courses of action. Decisions are made in a series of steps where each succeeding step depends upon the outcome of the preceding step.

As decision in each step is taken under conditions of uncertainty, the decision-maker:

1. defines alternatives,

2. estimates probabilities for various events,

3. calculates expected pay off from action for different alternatives.

Thus, the alternatives and their outcomes are represented graphically that help the decision maker in making the final decisions.

“Decision-trees depict, in the form of a ‘tree’, the decision points (represented by the square), chance events (represented by circles), and probabilities involved in various courses that might be undertaken”. It shows values for each option under positive and negative conditions.

Constructing a decision tree involves the following steps:

1. Define various alternatives.

2. Estimate probabilities for various events based on managers’ own experience, experience of others and market trends.

3. Compute payoff in various events for each alternative. This is done by multiplying the probability of the event with the expected payoff of that alternative.

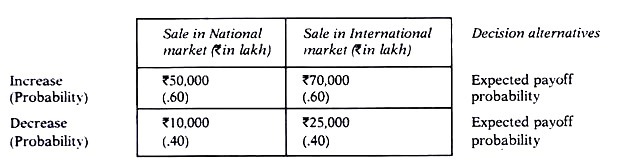

For example, a firm wants to launch a product which can be sold in the domestic market or international market. In this case:

The decision alternatives are:

1. Sale in national markets,

2. Sale in international markets.

Probabilities of various events are:

1. Increase in sale in national markets = .6

2. Decrease in sale in national markets = .4

3. Increase in sale in international market = .6

4. Decrease in sale in international market = .4

Expected payoff for each alternative

1. Increase in sale in national markets = Rs. 50,000

2. Decrease in sale in national markets = Rs. 10,000

3. Increase in sale in international markets = Rs.70,000

4. Decrease in sale in international markets = Rs. 25,000

The probability chart for increase or decrease in sales in the national and international market is as follows:

Total value of sale in the national market is (50,000) (.60) + (10,000) (.40) = Rs. 34,000, and international market is (70,000) (.60) + (25,000) (.40) = Rs. 52,000. Since value of sale in international market is more than national market by Rs. 18,000, it is advantageous for the firm to launch the product in the international market.

This can be diagrammatically represented as follows:

With increase in decision alternatives and chance events, it becomes difficult to make the decision tree manually. There may also be changes in decision points over a period of time. Initially, the product may be launched in the national markets but firm may decide to go international after some time.

There may also be changes in product features resulting in change in probabilities of their success or failure. All this makes construction of a decision tree complicated. In such cases where large volume of information has to be processed resulting into complex decision outcomes, managers make use of computers. Computers have facilitated easier and faster calculations of information for making use of decision tree.

(g) Queuing theory:

It describes the features of queuing situations where service is provided to people or units waiting in a queue. When people or materials wait in queue (because of limited facilities), it involves cost in terms of loss of time and un-utilised labour. Queuing theory aims at smooth flow of men and material so that waiting time is reduced.

This involves additional cost also. Thus, a balance is maintained between the cost of queues and cost incurred to prevent the queues. Queuing models in software packages have made their application feasible. This theory is usually followed in banks and ticket counters. It helps in determining the number of counters so that customers have to wait for minimum time.

It may also happen sometimes that there may not be people or material waiting at the queues.

Thus, there may be:

1. Excess waiting time as there are not enough facilities to serve the queue.

2. No waiting time so that the facilities are lying idle.

In the first situation, when facilities are inadequate to serve the customers or materials, the customers may go elsewhere or production process may get delayed. This will result in loss of revenue for the firm. In the second situation, when facilities are in excess of customers or material, facilities will remain idle or underutilised. Cost incurred in providing these facilities will exceed the revenue expected to be generated from them. This will increase financial burden of the firm.

Queuing theory helps in deciding the optimum number of queues required to optimally utilise the processing of people or material who need the services of those queues. It determines the optimum number of queues, number of servers at each queue, how efficiently those servers provide the services, rest time required for various servers etc. This is done by keeping into account the average rate at which material arrives, the average processing time, average waiting time etc.

If number of people or material is not too large, number of queues required can be estimated by observation but if this number is large, sophisticated queuing or waiting line models help in deciding the optimum number of queues so that neither the material or people have to wait in the queues nor the service providers lie vacant or underutilised.

(h) Gaming theory:

This theory was developed by Von Neumann and Morgenstern. It helps organisations face their competitors. This theory was initially developed to deal with problems related to wars. It aimed at deciding the actions of army so that it could frame a counter strategy to sense the actions of opposing army.

This theory does not aim to find the winning strategy to win over competitors but only an optimum strategy that helps to deal with competing moves of the competitors. The courses of action are made by the competing parties simultaneously assuming that the other party will react in the same way as he does. The decision is not made after the opponent’s course of action is already taken.

Apart from judging the actions of opponents in army, this theory is also used in marketing, election campaigns etc.

It helps the decision maker in making decisions under competitive situations. He makes decisions for situations whose outcome depends on his own actions as also actions taken by competitors who are faced with a similar problem. It specifies what competitors shall do in similar situations. If company X changes its plans; say reduces the price to increase sales, it is likely that competitors will do the same. How well is company X prepared to face this challenge and still continue with its changed plans is decided through games theory.

It is a technique where two decision-makers maximise their welfare in the competitive environment. The decision maker puts himself in his competitors’ shoes. He plans a counter strategy based on the thinking that if he were to compete against his own firm, what would he do.

(i) Network theory:

The network techniques plan and control the time taken to accomplish a project. They break the project into smaller activities and find the time taken to accomplish each activity. If actual time to complete the project is more than the time determined, it calls for corrective action. PERT (Project Evaluation Review Technique) and CPM (Critical Path Method) are the important network techniques which help in planning and controlling the projects, in terms of time and cost.

2. Modern Techniques for Making Non-programmed Decisions:

The following techniques help in solving novel, non-routine and unstructured problems:

(a) Creative techniques:

These techniques use creativity to think of innovative ways of solving problems. Members of the group give maximum suggestions to generate alternative solutions to the problem. Together, these ideas help to formulate the most practical solution to the problem.

The following techniques promote creativity in group decision-making:

(i) Brainstorming.

(ii) Nominal group technique.

(iii) Delphi technique.

(i) Brainstorming:

All members of the group associated with decision-making think and generate new ideas of doing a particular task. It generates as many ideas or decision-making alternatives as possible for solving a problem. Brainstorming means use of brain for generating ideas. The ideas are generated by a group where all members contribute to solve the problem.

It works as follows:

(a) The problem is clearly identified and presented to the group so that members can completely concentrate on the problem.

(b) Members give ideas to solve the problem. The aim is to generate as many ideas as possible as the focus is on quantity and not quality. Though all the ideas may not be useful, it generates a list of ideas some of which may be useful in solving the problem. Members are not inhibited by financial or organisational constraints in generating ideas. There is free flow of communication amongst members so that maximum number of ideas are generated.

(c) No idea is criticised because the purpose of brainstorming is to promote idea generation rather than limit the alternatives. Evaluation of ideas is done at a later stage. Brainstorming promotes creativity as members feel enthusiastic and energised to offer ideas which they feel are important for decision-making.

(ii) Nominal group technique:

Without criticizing the ideas offered by members of the group, all the suggestions are evaluated against each other and the final outcome is selected which represents consensus of members. Nominal group technique restricts communication amongst group members. It resolves conflicts by allowing group members to rank the ideas in the order of priority.

It works as follows:

(a) The group leader outlines the problem to the members.

(b) Every member writes his idea independently and gives his opinion about the best solution.

(c) After all the members have written their ideas, they are presented to the group or put on a board for discussion and evaluation.

(d) After discussion, the ideas are ranked in the order of priority by the members and a general consensus is arrived at. If no decision is made, the voting and ranking procedure is repeated until the final decision is concluded.

(iii) Delphi technique:

This technique is useful where respondents are geographically spread over large areas and do not have face-to-face interaction with each other. In this technique, a questionnaire is prepared and mailed to the respondents.

They fill the questionnaire and mail it back to the sender. The results are tabulated and used for designing a revised questionnaire. This is again sent to the respondents along with the original results. This helps them in giving subsequent responses to the questions. The process is repeated until consensus is achieved on finding solution to the problem.

Since this is a written form of finding solutions to the problems, the respondents express their opinion freely. They are not pressurized by personal biases and prejudices. However, this is a time-consuming method of collecting responses and should be used only if time for making decisions is not a constraint.

(b) Participative techniques:

Employees and managers jointly arrive at the decision. If those who make decisions and those who implement them jointly participate in the decision-making process, the quality of decisions will be better, there will be commitment to the implementation process and high employee motivation and morale.

(c) Heuristic techniques:

These technique represent trial and error approach to decision making. Decision maker accepts that strategic decision-making in complex situations is not easy. There are role conflicts, information gaps, environmental uncertainties etc. which make decision-making difficult. Heuristic techniques help decision-makers proceed in a step wise manner to arrive at a rational decision.

These are computer-aided techniques where decision-making is supported by computers. Managers access information from the data processing system, retrieve data relevant to the decision, test it for alternative solutions and accept the most appropriate solution. They change the variables in the form of inputs and analyse their impact on the desired output.

Regression analysis is one of the computer based systems which helps in the decision making process. The system supports the ability of managers to take decisions through judgment and creativity. An alternative to decision support system is group decision support system where decisions are collectively taken in groups in meetings and seminars.

Essay # 7. Models of Decision-Making:

Models represent the behaviour and perception of decision-makers in the decision-making environment. There are two models that guide decision-making behaviour of managers.

These are:

1. Rational/Normative Model

2. Non-Rational/Administrative Model

1. Rational/Normative Model:

This model assumes that decision-maker is an economic man as defined in the classical theory of management. He is guided by economic motives and self-interest. He aims to maximise profits and ignores behavioural and social aspects in making decisions.

The model presumes that decision-makers are perfect information assimilators and handlers. They can gather complete and reliable information about the problem, generate all possible alternatives, know the outcome of each alternative, rank them in the best order of priority and choose the best alternative. They follow a rational decision-making process and, therefore, make optimum decisions.

This model is based on the following assumptions:

1. Managers have clearly defined goals. They know exactly what they want to achieve. They have clear ends and know the means to reach those ends.

2. They can rank their preferences of decision outcomes in a hierarchy and make the right choice to maximise the organisational goals.

3. They can collect complete and reliable information from the environment to achieve the objectives.

4. They are creative, systematic and reasoned in their thinking. They can identify all alternatives and their outcomes related to the problem.

5. They can analyse all the alternatives and rank them in the order of priority.

6. They are not constrained by time, cost and information in making decisions.

7. They can choose the best alternative that will maximise returns at minimum cost.

The model assumes that the decision-maker is completely rational, that is, his action is completely intelligent and appropriate to reach the desired ends. He can select his behaviour out of various behaviour alternatives by evaluating the consequences of each behaviour in terms of value maximisation.

According to Simon, rationality can be understood in different contexts:

1. Objectively rational:

A decision is objectively rational if it is the correct behaviour that maximises given values in a given situation.

2. Subjectively rational:

A decision is subjectively rational if it maximises value relative to knowledge of the decision-maker.

3. Consciously rational:

A decision is consciously rational if the decision-maker consciously chosen the means to achieve the ends.

4. Deliberately rational:

A decision is deliberately rational if the decision-maker deliberately adjusts his means to the ends.

5. Organisationally rational:

A decision is organisationally rational if it is tuned to maximise the organisational goals, in particular, the profits.

6. Personally rational:

A decision is personally rational if it aims to maximise personal goals of the decision-maker. The rational model focuses on organisational rationality that aims to maximise profits for the organisation.

Limitations of the model:

Actual decision-making is not what is prescribed by the rational models. These models are normative and prescriptive. They only describe what is best, what decision-makers should do to make the best decisions and describe the norms they should follow in making decisions. They do not describe how decision-makers actually behave in different decision-making situations (This is explained in the non-rational models). They only describe what is the best. The best is, however, not achieved in real life situations.

This is because of the following constraints that managers face while making decisions:

1. They face multiple, conflicting goals and not a well-defined goal they want to achieve.

2. They are constrained by their ability to collect complete information about environmental variables. Information is future-oriented and future being uncertain, complete information cannot be collected. They cannot have information about all the alternatives. Even for a single alternative, they cannot collect complete information. They have to make assumptions about certain aspects of the decision-making situation.

3. They are constrained by time and cost factors to assimilate the information. They are limited in their search for alternatives that affect the decision-making situations. The decisions are based on information that managers can gather and not complete information. Even though more information is required to make decisions, decisions are based on partial information because of limited time available with decision-makers. Most of the non-programmed decisions are made under conditions of incomplete information.

4. They are constrained by their ability to analyse every factor that affects the decision- process. They have limited knowledge to assess all the alternatives. They cannot anticipate the outcomes of alternatives as they will be known only in future.

5. They may base decisions on subjective and personal biases. They consider only those facts which they think are relevant for decision-making. Personal preferences also affect choice of alternatives.

6. Continuous researches, innovations and technical developments can turn the best decisions into sub-optimal ones. Managers are, thus, constrained by technological factors.

7. Changing economic and social factors (economic and political policies, socio-cultural values, ethics, traditions, customs etc.) restrict their ability to make rational decisions.

8. Every manager has a value system which guides his decision-making behaviour. Personal preferences affect the quality of decisions. Perceptions about various alternatives affect the choice of alternatives and situations under which they will apply.

Every new manager looks at the same problem in different ways, interprets it differently and takes different decisions for similar problems dealt with other managers in the past.

9. People view organisational problems from personal angles. Marketing, human resource and finance managers do not view the organisational problem in the same way. They take different view of the same problem and generate different alternatives.

Individual perception, thus, makes different people see the same problem differently and, therefore, offer different solutions to deal with it. People see what they want to see and act accordingly. (While marketing manager may want to appoint more salesmen to increase sales, human resource manager may prefer to train the existing sales force rather than appointing more salesmen).

10. Power and politics at the work place also affects rationality of decisions. Final decisions are generally the outcome of interaction amongst many people at different levels who hold different views and interests in the decision. Decisions at lower levels are filtered before they reach the top and the final decision, thus, does not take complete view of all those who have been party to the decision. Decisions reflect the opinion of a few and not all.

Also, managers at higher levels use politics to acquire more power. Politics becomes a part of organisational working, whether or not managers like it. People use politics to get important and large projects through which they come in contact with influential people and also make money. This helps them build their power base. Politics is, thus, the way of working in a manner that a person is able to influence the behaviour of others.

11. Most of the organisational decisions represent multiple views of managers at different levels. People in the group have conflicting objectives. Choices are made through bargaining where clashes amongst various interest groups are sorted out. The final outcome or decision does not reflect the view point of all the managers and, thus, all alternatives are not considered while making decisions.

Perfect rationality, thus, cannot be achieved as:

1. The conditions under which decisions are made by the economic man do not exist in real business situations and

2. Even if they exist, they do not always aim to maximise profits. Business concerns have to cater to other social objectives also as demanded by environmental forces.

2. Non-Rational / Administrative Models:

Non-rational models are descriptive in nature. They do not describe what is best but describe what is practical in the given circumstances. They believe managers cannot make optimum decisions because they are constrained by internal and external organisational factors.

They cannot collect, analyse and process perfect and complete information and, therefore, cannot make optimum decisions. Absolute rationality is rare. It is seldom achieved. Based on maximum information that decision-makers can gather and process, they arrive at the best decisions in the given circumstances. These decisions are able to meet their standards. They are good enough and do not put undue pressure on time and resources. They are easy to understand and implement.

They are made within the constraints of available information and ability of managers to process the information. These decisions are not optimum decisions. They are satisfying decisions. Making decisions within the limitations of managers to collect complete information for decision-making and their ability to optimally analyse them is known as ‘principle of bounded rationality’. This principle was introduced by Herbert Simon.

This model is realistic in nature as it presents a descriptive and probabilistic rather than deterministic approach to decision-making. Rather than searching for all alternatives for making decisions and analysing their outcomes, decision-makers use value judgment and intuition in analysing maximum information they can gather within the constraints of time, money and ability and arrive at the most satisfying decision. This model does not represent optimum situation for decision-making. Instead, it represents the real situation for decision making.

The decision maker is not an economic man but an administrative man who combines rationality with emotions, sentiments and non-economic values held by his team members. He follows a flexible approach to decision-making which changes according to situations. Managers make feasible decisions which are less rational rather than rational decisions which are less feasible.

Rather than searching for all alternatives to maximise the decision outcome, the decision maker searches for alternatives that give optimum decision that meets the minimum criterion for its acceptability. Thus, he satisfies or optimizes instead of maximising.

It defines actual role behaviour (what the managers actually do in decision-making situations) rather than role prescription (prescribing what managers should do in decision-making situations). Searching every alternative is costly and once a satisfactory decision is made, searching for further alternatives at additional cost may not be worth the benefit to be derived from those alternatives.

“Bounded rationality refers to the limitations of thought, time and information that restrict a manager’s view of problems and situations.” — Pearce and Robinson

“Managers try to make the most logical decisions given the limitations of information and their imperfect ability to assimilate and analyse that information.” — Herbert Simon