The entrepreneurship in the context of ICTs is discussed under the three broad heads: 1. ICTs in creating Entrepreneurial Opportunities 2. Developing Insights from the Select Cases 3. ICTs in developing and Sustaining Entrepreneurial Capabilities.

Entrepreneurship development of yester years was not same as today. The concept is being changed rapidly. As the basics of entrepreneurship are going to be same, the way that is being carried out is changing fast. ICTs are playing important role in enhancing the efficiency of entrepreneurial activities on one hand and are creating new opportunities on other hand. These entrepreneurial opportunities are discussed under “ICTs in creating Entrepreneurial Opportunities”.

In the context of interwoven nature of entrepreneurship with the rural development and macroeconomics, it is important to bring forth some cases as how these two concepts will go hand in hand. Harnessing ICTs in the rural development have been well documented, but the inherent strength with respect to the entrepreneurial backdrop was often ignored. Hence there is a need to closely examine ICTs, rural development and entrepreneurship.

An attempt is made to discuss about the select cases where all these dimensions are well addressed. This is covered under the head “Developing Insights from the Select Cases”. All the stages of entrepreneurship development from development to sustenance stage are influenced by information, communication and networking.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Future entrepreneurial capabilities will depend largely on these three dimensions and ICTs are going to play an important role in bringing about efficiency in all these dimensions. Three cases are described under “ICTs in developing and Sustaining Entrepreneurial Capabilities” will give insights as how few initiatives were started in India and elsewhere.

ICTs in Creating Entrepreneurial Opportunities:

Of late, young people are using ICT as a launching pad for initiating a range of entrepreneurial activities. With ICTs it is possible to explore low-income generation opportunities, involving telephony and the use of mobile phones, role of young people as information intermediaries, e-commerce and establishment of telecasters. Many of such paradigm shifts have been observed for last one decade and have potential to be generalized for over all entrepreneurship development.

Selling Telephone-Based Services:

The worldwide expansion of mobile phone networks and the growth in the number of mobile phone subscribers has been phenomenal in recent years.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The availability of mobile phone networks in India opens up many opportunities for young people. One common option is to purchase a mobile phone through a micro credit program and to earn income by providing low cost phone calls to others. This is a very common income generating opportunity for rural youth in India. One example, among others is setting up of Tata Indicom PCOs in villages.

To further develop some insights as how mobile telephony entrepreneurship could be institutionalized, a case of Grameen Village Pay Phone program (VPP). Grameen Bank is a pioneer of small loans to the poor. The Village Pay Phone program makes it possible for a Grameen borrower to buy a mobile phone, and then to make the telephone available for others in the village to pay for phone calls, to send short message services (SMS) and to enable villagers to receive incoming calls.

Grameen Telecom charges Grameen borrowers a wholesale airtime rate. Grameen Village Pay Phones operates in more than 2,000 villages in Bangladesh and an average of 100 additional villages is being connected each month. A typical pay phone owner can earn up to four times the average per capita income in Bangladesh.

The phones are used for a variety of purposes. Farmers use them to find out where they can get the best prices for their crops, and relief workers are able to better coordinate disaster response measures. Villagers are also able to use the phones to communicate with local government officials.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Grameen Telecom is itself is a good example of entrepreneurial activity supported by partnerships with international agencies, international companies and other funding sources. The potential of Grameen Telecom as an income generator has been acknowledged by an international agencies and could be viable model for countries like India.

Tech-Mode Information Intermediaries:

India is an experimental country for the world to pilot test thousands of ICT projects aimed at rural development. Based on the success of several ICT projects, government of India has taken up several e-strategies to harness the power of ICTs for societal transformation. In many of such initiatives content, connectivity and capacity building have been identified as pre-requisites.

In this back drop it is observed that the widespread use of English on the Internet has created the need for local content and applications to enable non-English rural Indians to make effective use of it. For the poor in particular, the vast amount of information on the Internet requires an intermediary to identify what is relevant and then interpret it in the light of the local context. Young people are well placed to perform this role of ‘information intermediary’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A study conducted by Shaik N.Meera (2004) revealed that ICT projects to serve resource-poor farmers require qualified and well-motivated staff to serve as an interface with computer systems. This is a good opportunity for rural youth in near future. Ministry of Information Technology and National Institute of Smart Governance, Alliance 2007, and many more initiatives aim to establish Village Knowledge Centres (VKC) with a motto of every village a VKC. These Knowledge centres are going to be run by several young entrepreneurs who are imparted training by several institutes such as Jameshedji Tata National Virtual Academy.

Another option is for young people to use their skills in information technology to develop simple web sites/web pages/local content in local languages. For example, Swaminathan Foundation has set up Village Knowledge Centres, with special websites to provide a variety of locally relevant content.

Another example is Warana Nagar rural network project, in Maharashtra. The district has 70 villages and is known for the strength of its cooperative societies. Villagers are using ‘facilitation booths’ to access agricultural, medical and educational information on the Internet.

E-Commerce-Based Entrepreneurship in Remote Communities:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Other low-income generating opportunities available to young people in remote locations is initiating e-commerce based entrepreneurship development. The Los Angeles-based Green Star Foundation is setting up self-contained, solar-powered community centres in remote communities in India.

Each centre offers an Internet connection, health facilities, including telemedicine, a classroom complete with distance learning equipment, and a business centre, through which traditional cultural products can be sold via the Internet. Traditional art, music, photography, legends, and storytelling in small villages can be recorded and brought to global markets through the Internet.

The projects are deliberately targeting areas without electricity. The approach is to use this market mechanism to sell cultural products in digital formats to pay for the hardware and connections needed and to produce ongoing revenue without the need for external funding. The projects are the product of public-private collaborations between governments, local ICT companies and international funding sources.

To generate income through e-commerce, Green star is encouraging a team of artists and teachers to record elements of rural Indian culture, working closely with the people of each village. The result is a powerful, unique collection of ‘digital culture’ – a gallery of music, artwork, photographs, video, poetry and other arts, which can be distributed in high-resolution digital form throughout the world, instantly and efficiently. The revenues from digital culture are used to fund basic needs of each village for its future, as decided by the people themselves.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Bridging the Gap between the Digital Economy and the Informal Sector:

Another paradigm is the use of ICT to help bridge the gap between young people’s opportunities for self-employment in the informal economy. For example, the Foundation of Occupational Development in India, which operates eleven telecentres, has also established a website called India Shop to provide a market outlet for indigenous crafts people.

As a result, an isolated community is able to fetch much higher prices from international customers than from retailers in nearby cities. Reference has also been made to how communities in remote locations can make use of self-contained, solar-powered ICT centres to sell, among other things, traditional cultural products such as art, music, photography, legends and storytelling via the Internet. This is being done on a pilot basis in remote communities in India.

Another example of the use of ICT to help bridge the gap between employment for young people in the informal sector and the mainstream economy is India’s Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA). Its 2,20,000 members are women who earn a living through their own labour or through small businesses. SEWA has been one of the first organizations in India to realise the potential for harnessing ICT to help women in the informal sector.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It has sought to develop the organization’s capacity to use computers by conducting awareness programs and imparting basic computer skills to its team leaders, ‘barefoot’ managers and members of its various member associations. Many of SEWA’s member organizations have launched their own websites to sell their products in the global virtual market place.

Since the entire membership of SEWA consists of poor self-employed women, giving its members access to software in the ‘language of daily use’ is of great importance. Hence, efforts are being made to develop software to enable grass-roots workers and members to make the best use of the tools provided by ICT. Recently, SEWA has started using telecommunications as a tool for capacity building among the rural population.

SEWA uses a combination of landline and satellite communication to conduct educational programs on community development by distance learning. The community development themes covered in the education programs delivered include: organizing; leadership building; forestry; water conservation; health education; child development, the Panchayati Raj System and financial services.

Middle-income entrepreneurial opportunities can also be identified involving the use of ICT in the service sector. ‘Mini telecentres’ usually offer a single phone line (possibly mobile phone) with a three-in-one scanner/printer/copier, a fax machine and a PC with a printer, Internet access and a call meter. A ‘telecentre’ offers a number of phone lines, a call management system, fax machine, photocopier, several PCs with a printer, Internet access and perhaps a scanner.

Finally, a ‘full service telecentre’ offers many phone lines and multimedia PCs with Internet access. Other equipment can include a high-volume black and white and/or colour printer, a scanner, a digital camera, a video camera, a TV, an overhead projector, a photocopier, a laminator, meeting rooms, and a video conferencing room.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

India has seen a rapid growth in ‘cyber kiosks’ or ‘telekiosks’ which can provide access to business support services for underprivileged groups. These ‘Internet kiosks’ are often upgraded STD (Subscriber Trunk Dialing) booths that are common in India. These are small street shops, offering access to public phones for long distance calls. They number about 300,000 and have generated more than 600,000 jobs.

Promoting Public-Private Partnerships to Generate ICT-Related Employment:

Use of public-private partnerships to create ICT-related employment opportunities for young people is another untapped area. Public-private partnerships refer to collaborative arrangements between governments and private enterprises or the NGO sector to generate employment or to deliver better services.

One benefit of public-private partnerships by governments is to leverage additional investment to build public infrastructure or to deliver public services using private providers. Public-private partnerships can help leverage ICT-related employment because Governments need to attract not only investment funds but also the knowledge and expertise required to operate complex ICT facilities.

Young people have the opportunity to gain employment through the growth in remote processing facilities that are located outside the high-income countries. These provide a range of services from help lines, technical support, and handling reservations and sales to data conversion including voice to data transcription.

Other remote processing includes payroll accounting to internal auditing and credit appraisals. High-end remote processing includes creating digitized maps of townships, utilities, roads, and other facilities. It is claimed that back office functions likely to grow in importance are settling insurance claims and summarizing legal documents, such as witness depositions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Call Centres:

A related source of ICT-generated employment for young people is through Call centres. These offer telephone-based services from a central office to customers in a variety of business sectors. Call centres handle telephone calls, fax, e-mail and other types of customer contact – in live and automated formats. Many young people in India have found work in call centres.

Developing Insights from the Select Cases:

Many a times, promoting sustainable livelihoods of the rural people using ICTs is linked to the entrepreneurial development of the rural youth. At times ICTs may help rural people (irrespective whether youth or not) to change the old ways of doing the business and in becoming entrepreneurs of their own. These cases must be looked at with a view as how some ICT initiatives are creating entrepreneurial opportunities along with serving to bring about sustainable development of rural areas.

Enterprise Management Using ICTs: Case of Ascent:

Athani, in the State of Karnataka is the heart land of Kolhapuri sandals and home to over 400 such families of artisans with a rich legacy. Footwear craft is their only livelihood. Prior to year 2000 most worked as low wage-bonded labour in footwear ‘factories’ owned by dominant traders.

Their life and craft were demeaned – they lived on the very edge. Prior to 1998 skill training and technology up gradation intervention was targeted at men, apart from training some tools were provided which found their way to markets rather than application.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It would not be wrong to state that the intervention was not gender inclusive, women were not reckoned as artisans even though it was an established practice that men fashion the hardy soles and women craft the intricate uppers with a role division. ASCENT initiated Project Enterprise (Jan 1999 – Dec 2002) sponsored by UNDP with technology support from CLRI (Central Leather Research Institute) and infrastructure by Government of Karnataka, the project objective was ensuring right price for the handcrafted footwear and transforming artisans to entrepreneurs, particularly women.

The core focus was economic development and the core principal was – build, operate and transfer. The business front end and social back end needed constant balancing using an equality, equity and inclusive approach.

The outcome of this intense joint effort is ToeHold Artisans Collaborative (TAC). From a business perspective TAC has been an overwhelming success. The operation has achieved robust revenue growth in recent years and is achieving healthy profits, which are redistributing amongst artisans and self-help groups (SHGs) of women in Athani. TAC is now a prominent player in the international market for ethnic footwear supplying international clientele in UK, Italy, Japan and Australia.

The artisans formed their collaborative called the ToeHold Artisans’ Collaborative in October 2000 with their own brand ‘ToeHold’. The brand is targeted at the niche segment or the class markets rather than mass markets for optimum profitability. The footwear is positioned as ‘fashion accessory’ and not just as craft. 150 women organized into eleven women Self Help Groups jointly exercise ownership of the collective.

A Common Facility Center and Raw Material Bank with a Design Studio are set up at Athani (in two Vishwa sheds). The artisans -women and men, receive joint training in design development, entrepreneurial skills and leadership and soft skills. Artisans’ direct exposure to international markets has improved their understanding of the international customer and the demands in terms of quality, delivery commitments and design. Each family now acts as a micro enterprise where the woman and man are ‘co-preneurs’. The financial stakes are with women but men are equal partners to all other activities and inputs.

A vast collection of contemporary new designs has been developed. ToeHold Artisans’ Collaborative exports to very competitive mainstream international fashion markets. The ToeHold artisans went on to participate in the India International Leather Fair, Chennai, Delhi Shoe Fair and in the GDS International Shoe Fair in Dusseldorf, Germany and International Leather Fair in Shanghai. By now, they were more receptive to new ideas and ready to understand the concepts of costing and pricing, and so far, these teams from Athani executed export orders worth nearly USD 225,000.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This unique model of enterprise, owned and governed by the artisans through women’s Self Help Groups has taken the humble ‘Kolhapuri’ to ‘couture’ status in the trendiest mainstream international fashion markets. This can act as a learning model for similar efforts in other sectors as well.

This also throws light on the importance of artisan clustering and the ways in which some 2000 already existing artisan clusters in India can be helped with successful interventions from the state and civil society organisations. The model where SHGs manage the enterprise is an idea with much applicability and can be replicated for many kinds of enterprises.

Social Entrepreneurship Model: Case of Akshaya:

The highpoint of the Kerala Model of development in the social sector is attributed to the creation of access points. Kerala has government owned access points in all the core sectors of development. A primary school for 1000 families, ration shop as the part of public distribution system,’ Anganwadi’ for prenatal care, primary health centres for medical care etc.

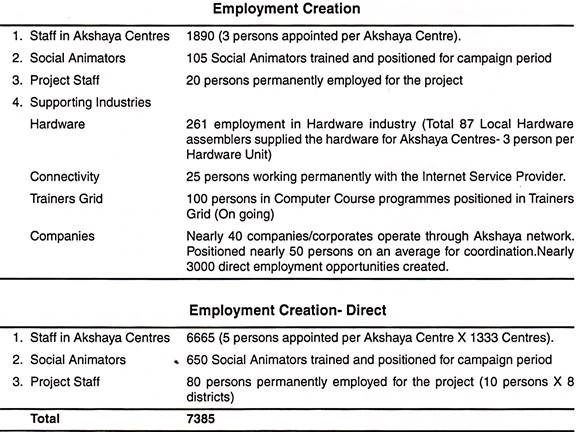

Access points were established owned and maintained by government. Setting up 5000 ICT centres, managing them, and to dynamically update the situations will be very difficult for the State Government primarily because of the constraints in the resources. It was therefore decided to start the centres with the help of local entrepreneurs. The huge unemployment percentage of the educated youths in the State also prompted the State Government to take this decision.

The concept of social entrepreneurship was brought in here, because of two reasons; one ICT for Development in the rural areas is a new concept, people have not started using ICT in their lives, except for the fact that some services like railway reservation are used without realizing it as an intervention by Technology. But to prompt the people to use Internet instead of telephone calls or online payment system to pay their bills is not an easy job, because of the hesitation to use technology.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A Social entrepreneur, who is a native of that place, commands some social esteem, is well versed in social activities, badly in need of a job, ready to experiment, would be able to define the information, communication, and education needs of the common people around him, and to covert the need to a service with the help of government. Entrepreneur in Akshaya is clearly understood the fact that service delivery through his centre is an essential component for creating his business and maintaining the customer base. Many training programmes were organized for Akshaya entrepreneurs.

Akshaya Centre is owned by a single entrepreneur. There can be partnership firms, trusts, companies that start Akshaya Centres. But Local Bodies sign the agreement only with a single person easy operation of the arrangement. Akshaya entrepreneurs have to sign an agreement with government where he undertakes to start and run the centre for a period of three years.

They are committed to do all the projects initiated by government during this time span. He has to sign a code of conduct to work as a social and economic catalyst by demonstrating the high spirits of democracy and perform the duties of a better citizen. Also he cannot indulge in any kind of immoral or antisocial activities. Government can any time cancel the centre, if it violates the guidelines.

If the Akshaya Centre functions from a rented premise, Akshaya Entrepreneur has to sign a three year contract with the Building owner to maintain the centre at the same location for a minimum of three years. If the building is his own, he has to give an undertaking on Rs.50 Stamp paper, to maintain the Akshaya Centres in the same place for three years. The Centre owner has to secure the permission of Grama Panchayat and District Level Project Monitoring Agency and from the other entrepreneurs in the Panchayat for shifting the location.

Akshaya Centres Operate from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. But during the e-literacy phase, there are centres which are working more than 18 hours a day. Akshaya Centres can open sub-centres with the permission of local bodies to extend the services. During Malappuram e-literacy phase more than 2000 sub centres were opened by 630 Akshaya Centres.

Akshaya Centres required to use proper records. There are two registers, which is used for monitoring the e-literacy campaign by local bodies. Two types of registers will be made available, the main register has to be maintained in the main centre, and separate registers are to be maintained for sub centres.

Delivering IT Power to Villages: Case of Rajiv Internet Village:

Rajiv Internet Village (RAJiv) is an e-governance initiative, conceptualized and started by e-Govt. Services and powered by Sun Microsystems’ open source infrastructure. Supported by government of Andhra Pradesh and leading banks such as State Bank of India, the initiative involves identifying local entrepreneurs and giving them complete support to set up an e-commerce kiosk. This kiosk offers a wide spectrum of services to the local residents, thus not only benefiting the entrepreneur to earn from transaction commissions, but also enables the entire village to benefit with services, which this kiosk brings to their doorsteps.

Around 73 kiosks have been set up under the project so far and already more than 2.8 lakh transactions have been implemented on the network. Right from project financing to the various services it offers, care has been taken to ensure that it is not dependent on any government subsidies. New and unique services have been introduced to ensure continuity and sustainability of the business.

Using revolutionary open source infrastructure from Sun Microsystems, we have ensured that the project is easily executable, replicable and easily scalable. It is being estimated that in next two years, all 2,000 villages will be brought under the ambit of this project and around two million villagers will benefit from the e-commerce success. The AP government has already studied the project in detail and plans to implement it throughout the state, thus benefiting around eight million citizens.

Project is Offering:

i. G2C Services:

Varied certificated from government departments like caste certificates, birth and death certificates, residence certificates and income certificates.

ii. B2C Services:

Electricity bill payments of Andhra Pradesh Transmission Company Ltd; state bus tickets of Andhra Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation; telephone bill payments of BSNL, Reliance Info-comm and Tata Indicom; mobile bill payments of BSNL Cell One, Reliance Infocom, Tata Indicom and Airtel; railway reservations by IRCTC and courier service to transfer couriers from one mandal to another.

iii. Other Services:

Varied services like e-employment, information based services, Spandana for citizens petitions and grievances, e-education, computer aided learning, Azim Premji Foundation CDs, tele-health and entertainment will also be made available to the people.

The TeNeT Group at Indian Institute of Technology, IIT-Madras has worked over the past 2 years on a rural BPO initiative that links urban clients with a rural workforce through the internet kiosk network. The team identifies and trains workers in rural areas in various skills, relevant to the BPO industry. It liaises with urban clients and takes complete responsibility for the outsourcing and timely delivery of the projects undertaken, and ensures that quality standards are met.

As a coordinating agency, the team protects the interests of both the clients and the kiosks. At the village-end it filters out unproductive kiosks from the system, and at the city-end it runs due diligence checks on the client to guard against fraudulent BPO activity. This unique initiative has a portfolio of services that includes typing in English and regional languages, data entry operations, web and multimedia development and regional language translation.

More recently, engineering services such as 2D drafting and conversion of 2D to 3D for the manufacturing sector have also been introduced. While the model today runs on a smaller scale, a typical rural BPO centre, to be envisaged in the future, would consist of 10 PCs running in two shifts. Each centre would employ between 10-20 individuals, and the kiosk owner would be responsible for hiring and managing the staff, ensuring that timelines and quality standards are adhered to, and managing daily operations.

BPO activity in India is clustered around 5 main hubs today. These centres will continue to remain important in the future, but the industry is looking to expand to other locations for several reasons. Newer locations would imply access to a larger workforce, provide an opportunity to further reduce costs of operation, help acquire language-specific skills and mitigate overall business risk and ensure business continuity.

Expansion to newer locations would also help to reduce the pressure on infrastructure, being faced in the current locations. Rural areas can be attractive outsourcing destinations for the BPO industry primarily because labour is less expensive than in the cities. Also minimal investment in infrastructure is required in the existing kiosks in order for them to serve as BPO centres.

Rentals and overheads in these areas also tend to be low, further adding to the arbitrage. The most important leverage in this arrangement, however, is the existence of an entrepreneur running every kiosk, who is a trusted entry point into the village. Likewise, the Rural BPO model offers significant benefits to the rural population.

With IT training, the youth in rural areas are exposed to skills that are highly valued in today’s economy. As a result, their productivity and incomes increase, and so, also their personal confidence. The entire rural economy begins to thrive as more money flows into villages, allowing for more equitable economic growth at the national level.

An Internet Gateway to Promote Sustainable Livelihoods:

The potential for ICT to bridge the gap between young people’s self-employment opportunities in local informal sector markets and the wider domestic and international economy is amply demonstrated by India’s. TARAhaat or Star Marketplace is an Internet gateway that connects the village user to information about social services, health, entertainment, and to markets, through a network of franchised cyber centres, customised in the language of their choice.

The website attracts between 5000 and 25,000 contacts per month. The project illustrates a number of best practice features, which won it the 2001 Stockholm International Challenge prize as best practice in the category of a Global Village.

The first feature worth highlighting is that it is targeted at the poor by seeking to create sustainable livelihoods for people located in areas with limited economic opportunities and harsh living conditions.

Second, it has been designed using extensive market research and socio-economic surveys, including a house-to-house survey of selected villages in the region.

Third, its format aims to cater for the needs of people with wide variations in literacy, language, financial liquidity, and levels of understanding.

Fourth, the project is supported by partnerships with enterprises in the public and private sector including the Indira Gandhi National Open University.

Fifth, the project has support from youth organisations through the Association of National Youth Cooperatives.

Sixth, the project is based on features that go beyond simply using the Internet to communicate with its target audience.

TARAhaat covers all three components for rural connectivity- content, access and fulfillment. Content in relation to law, governance, health and livelihoods is provided by its mother portal. Access is provided through a network of franchised local enterprises. Delivery of information, goods and services is provided by local courier services or franchised TARAvans.

The revenue streams of TARAhaat provide for profit generation at each step of the supply chain, serving to further cement its networks. The project, although still in its pilot stage, is said to have increased the economic opportunities for the physically disabled and the franchisees, as well as to have improved access to education for rural girls. The main benefits include the generation of alternative sources of income for young people through desktop publishing.

ICTs in Developing and Sustaining Entrepreneurial Capabilities:

Entrepreneurship is not an easy option and is best suited to those with the necessary skills and acumen. Some of these skills can be acquired, even via the Internet. However, some skills such as risk taking and self-confidence may be more deep seated. Young people starting their own businesses are likely to experience a range of problems.

One fundamental problem is the inability to secure start-up funds leading to under capitalization (starting a business without enough funds). Other problems commonly encountered are managing cash flow, especially dealing with bad debts and late payments; and coping with stress, especially without the support of friends who understand the demands of self-employment. In such cases, ICTs may help young people in developing and sustaining their enterprise, using some concepts such as Business incubators. Nurturing and developing entrepreneurs may get some help from ICTs as discussed in these cases.

ICT Enabled Business Incubators:

Throughout the developing world, innovative entrepreneurs are working to establish businesses that are ‘ICT-enabled’-offering ICT services or, in some way utilising ICTs as a fundamental aspect of their business model. Technology entrepreneurship is key to innovation, employment, and national competitiveness. However, often the obstacles facing such start-ups seem insurmountable.

Common barriers to converting an innovative idea to a viable business venture include limited and costly access to Information and Communication services, burdensome business regulations, the absence of basic business support services, the lack of advice, mentoring and best practice guidance, limited market knowledge, and lack of access to appropriate financial services. In 2002, in response to these challenges infoDev launched the Business Incubator Initiative, aimed at fostering ICT-enabled entrepreneurship and private sector development in developing countries.

A business and technology incubator, and start-up resource centre with operations close to the innovation clusters in the Pune-Mumbai corridor. IndiaCo assists early stage companies by providing business infrastructure and office space, mentoring and coaching, and assistance in raising private equity capital. The goal is to increase the success rate of start-ups by operating a network that facilitates and motivates the use of local resources to commercialise available technologies.

Tiruchirapalli Regional Engineering College, Science and Technology Entrepreneurs Park:

TREC-STEP is the first Science Park to be promoted in India since 1986, which aims to foster knowledge based ventures comprised of young science and technology entrepreneurs. TREC-STEP has been promoted by Department of Science and technology, Government of India, Government of Tamil Nadu, Industrial development Bank of India (IDBI), Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India (ICICI), Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI) and state financial and Development organisations.

Society for Research and Initiative for Sustainable Technologies and Resources:

It aims to build and enhance an ICT-enabled virtual incubator model for scaling up grassroots innovations.

Telecommunications and Network Group:

TeNeT’s expertise spans digital communications, wireless networks, computers protocols, optical communications, digital signal processing, speech, audio and video technologies, among others. The TeNet Group engages in teaching and training, product development, incubation of technology companies, telecommunications, IT policy studies and front-line research.

Vellore Institute of Technology-Technology Business Incubator:

VIT-TBI was established at Vellore Institute of Technology with the sponsorship of the Government of India’s Department of Science and Technology. VIT-TBI assists budding entrepreneurs with incubating new technology ventures.

Promotion of Youth Entrepreneurship through ICT in Schools:

The School Internet Learning Centres in Uganda have been set up by the country’s Education Department to promote youth employment through giving young people entrepreneurship and leadership skills using ICT-based training and resources. The project was one of 100 finalists for the 2001 Stockholm Challenge. Some thirty ICT resource centres, each comprising ten networked computers and a server, with printers and modems, have been set up in Ugandan schools.

The resource centres service between 200 and 1000 young people per month. The goals of the project are to: develop youth leadership, team building and business skills; promote youth employment through linkages with local industry/business; create new youth led business opportunities and encourage young people to exchange business ideas and information via e-mail. Youth who participate in the project are given an opportunity to develop business concepts and plans that draw upon the ICT resources available at the centres.

Assistance for Young People to Set up Community-Based Businesses in Rural Areas:

World Corps, an international non-profit organization based in Seattle that provides training to promising young business and community leaders worldwide. World Corps seeks to create jobs, sustainable social business ventures, and programs for social change that are easily replicable. World Corps trains young men and women aged 21-28 to establish community- based businesses in rural areas of the developing world.

These young people train together in multi-national teams, and return to their home communities (primarily in the developing world) to establish small businesses in areas such as Internet and renewable energy. World Corps is launching its first Pilot Program in India in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh.

Starting in January, 25 young people (15 from India and 10 from five other countries) will train together for six months while establishing new community Internet centres in India. The new Internet centres will bring the resources of the Internet to poorer neighbourhoods outside large cities. Training topics in other countries will focus on other sustainable, environmentally friendly business enterprises such as renewable energy.

However, other forms of mentoring could also be fostered, involving short- term visits (both ways) and ongoing contact through e-mail. There are a range of resources on the Internet in relation to online mentoring.

The role of small and medium-sized enterprises in employment, growth and development is now recognized the world over. Entrepreneurship development has played a major role in the growth and development of economies. To achieve maximum gain from entrepreneurial abilities of rural Indians, there is a need to use cutting edge technologies such as ICTs. A more holistic ICT integration will help in networking and building of collaborative entrepreneurial clusters.

The focus of the paper is to show what could be possible with the ICTs blended entrepreneurship development. The cases discussed in the paper were proven to give some insights for future endeavours, there is a great need to work out ICT modules as how best ICTs can be utilized in the entrepreneurship development. The need for harnessing ICTs in entrepreneurship development is never acute than at present.